Imagining a Borderless Future

An interview with Portuguese writer, professor, and playwright Jorge Palinhos

The Saturday Brunch: a figurative flat white or fizzy to start your weekend

This week, I interviewed Jorge Palinhos who is a professor at the arts university in Porto (Portugal) as well as a writer and playwright who works at the intersection between the written word, life performance, and digital art. He has written a play about the African wars of independence and another about a Portuguese mystic poet: Daniel Faria. The cultural studies scholar’s work crosses many boundaries, functioning between mediums and disciplines in an organic way; he believes “everything is connected.”

Jorge and I connected through ACS, the Association for Culture Studies. We are both interested in international and interdisciplinary work. I was also interested in a recent short story Jorge had shared with me. “Tenho um plano” (“I have a plan”) was written for the purpose of adaptation for a family theatre production and is primarily a parable about border walls. I’ve investigated Walls and Borders in these past few weeks, so this was a welcome addition to the conversation.

Making connections

We start by talking about what Jorge teaches, clearly a source of creativity and inspiration for him. The other day, he had his class walk around a park’s labyrinth to search for what they would be writing. I posit that it sounds a lot like something Borges would do.

Jorge seems to spend a lot of time in the spaces of Porto, reflecting on their function and aesthetics. “I am involved in creating the artistic programming of a downtrodden area of Porto full of social housing with numerous marginal communities, like Roma, immigrants, etc. This programming sometimes involved creating performances, other times inviting other artists to do something.”

For him, this is a challenge on multiple levels: "On one hand, you cannot simply propose artistic objects which you think are good, and hope they will change the outlook of people. People there have their own culture, their own artistic practices, which are different, but not necessarily worse. What you are trying to do you is establish a dialogue, where you are trying to learn what people do, what people like, and propose performances which can be compatible, which can raise the awareness and the curiosity of people. But, on the other hand, you also must be willing to be transformed by the experience, be able to learn with the people of those areas, otherwise, no communication will ever happen."

“Everything is connected.”

Jorge tries to do “experiential teaching” when possible, but sometimes it is difficult to plan for. He discusses the many ideas he has in his writing, research, and teaching; the way they come together is often spontaneous. To me, it sounds like a kind of poetry, but Jorge defends that he “is not a poet” although he has written a book about a poet. Perhaps instead of writing down poetry, he lives through it.

He comes back to this idea of poetry, considering the way he has changed as a writer over the last twenty years:

I started writing for theatre [with a work] about a poet; and now almost twenty years later, I was asked to do almost the same thing. It’s interesting to compare the two projects….then I was completely naive. … I have become bolder, more confident maybe, and more able to know what I want (and don’t want) and able to establish a sort of artistic debate on stage.

Jorge came to academia after an established career as a writer-playwright. It seems a natural progression reflecting the above reflection on the way his artistry changed over the years. He is interested not only in the creation of the art itself, but the why and how as well as the impact art has on an audience and society.

While writing, he was working at a publishing house that was sold. So in the restructuring, he was laid off and began working as a translator. He then decided to start the PhD in cultural studies and was invited to teach at the same time. “Everything started evolving and becoming more intertwined.”

In discussing the evolution of his work toward academia as well, Jorge says: “I think the way my mind works is to try to connect everything, even things that don’t seem to be connected.” He speaks of teaching dramaturgy and finding his students playing cards outside the classroom. To the students, he likened the experience to dramaturgy, which at first confused the students. To him, it made sense philosophically. The world does not work in tiny unconnected categories: “I cannot separate those things. Everything is connected.”

As a teacher, he says, “I sometimes have to restrict myself, because if I go on, they will become very confused.” He does this also with video games, when he teaches writing for video games and digital media, asking: "How are you able to distinguish games from reality; what is reality? What is a game? This balance of pushing new thinking without losing your students is a constant struggle for teachers. Finding just the right amount of challenge is an art, but maybe we do not witness some of the responses to challenge in the classroom. If they happen years later, we have still succeeded. After all, education is not a sprint, but a marathon. Usually students want quick and efficient solutions for their problems. Once some students were to act in a Brecht play and wanted to know how to be brechtian actors. Do we say the text and stare at the audience to show them we are distanced? I told them: I believe the only way is for you to read the Manifest of the Communist Party. For Brecht, actors should be political actors, first and foremost. Not really the quick fix the students wanted, but maybe a more honest long-term solution.”

And sometimes, he discusses, “even I am surprised” by the students who can make connections in class. One particular student made a connection to Lord of the Rings from a medieval theatre course, which he explains further — both connect to Christian Mythology. It was interesting that the student was unable to name how they were connected, but with investigations, we find knowledge. Through this conversation, I imagine Jorge inspires many thinkers in his classroom.

A border parable

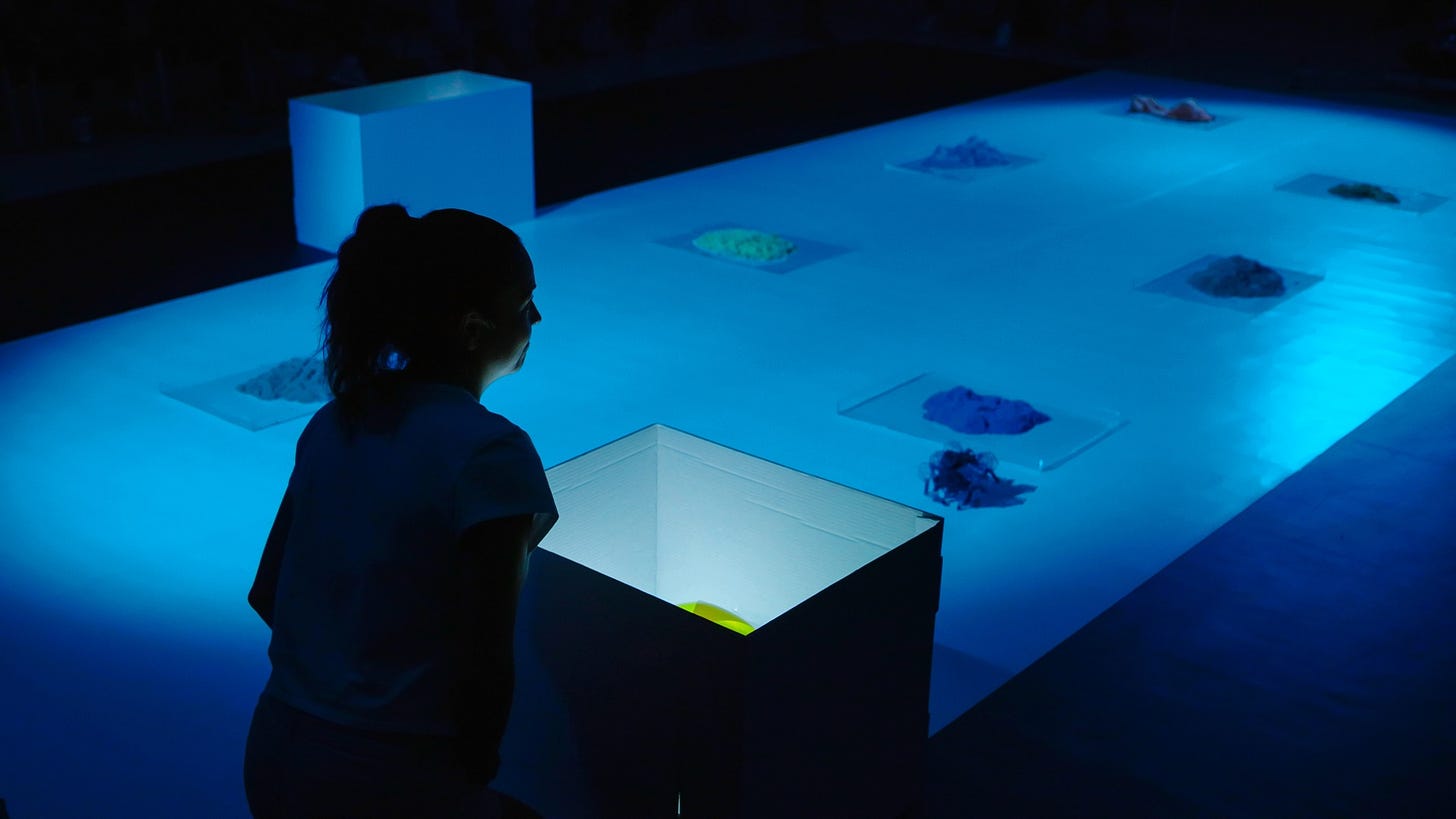

We return to the topic of his current project that has just recently shown in Esmoriz on November 5th, but hopefully soon again for reproduction. The short story “Tenho um plano” (“I have a plan”) was written with the intention of performance for a family audience. The company wanted “something about borders…that would be accessible to families and all ages. Which means you have to consider the most challenging audience: children.”

In the story, a boy builds a formidable sand castle without a door or windows. Another girl on the beach wants to add these openings, but instead they end up destroying the castle, which in turn becomes a kind of “corridor,” or perhaps liminal space. Eventually, the story ends, the ruined castle will be swallowed up by the “endless swell of the sea and time.”

“I imagine a borderless world. It’s natural, right?”

“I started thinking about lines, because of the frontier, which is something that is always shifting. A line is a rational construction that allows us to understand space.”He discusses the way his family comes from the border with Spain. He notices that people at the border have more in common with each other than those at a farther part of the country (i.e. at the Atlantic coast of Portugal). He felt this way in Strasbourg and crossing into Germany as well.

Having recently spent quite a bit of time in Alsace and Strasbourg since I moved to Basel, I can see exactly his point. This whole region to me feels distinctly German more than French. Even the food of sausages and creams with tart white wines is much more similar to what I know of Germany than what I know of Bordeaux or Biarritz, for example.

“I was also inspired by a book called The Atlas of the Body and the Imagination (Gonçalo M. Tavares) which is about the connection of the body with arts and space, bringing together the work of architects and theorists.” Additionally, he cites recent images of refugees passing through borders as inspiration for the parable. “I imagine a borderless world. It’s natural, right?”

But how to bring his ideas and those of spatial or political theorists to children? “Children cannot relate to borders. They just move around.” In this way, the parable comes back to a perhaps deeper question that seems simple on the surface: why have borders at all?

Jorge discusses bringing his daughter to a physiotherapist that morning. She was asked to perform tasks on a mat on the floor, but at some point she was drifting off the mat and moving her arm so that she fell: “Her face fell on the wrong side of the border: on the hard floor.” She had no feeling that there was safety or security on the mat, that the border represented any change at all. He says it with humor; clearly his daughter was not too fazed by the incident. Instead it was another real life metaphor of his ideas about the border and the way children experience the world.

Children are allowed to “make mistakes and learn from them. They also learn not to consider the border.” Jorge likens this concept to what he sees with his students. He posits that “at some point, children in their teenage years become rigid in their views of the border.” He tries to show his students that “strict definitions” are “actually really fluid.” He discusses that this is, however, a “long process” that is not always actualized in the classroom.

In other words, children maintain a stronger connection to nature:

There are never real borders in nature. The beach is also liminal space. It is between solid ground and the sea; there is no clear frontier. The sea levels are rising and there is a scary anticipation about parts of Portugal that will be flooded….and this also shows that this concept of earth and water that seem to be totally different things are really not. Most of what we call solid ground is really not solid; it is water, too.

In the story, the child speaks of his parents who will not always give him answers or reasons. I ask him if the adults are the protectors or antagonists to the children. It’s an “inevitable paradox” he replies. Children ask deep questions, to “the core of existence.” He experiences this with his nieces and cannot always answer the existential questions because “in a way if you reply, you are questioning everything. And this can be dangerous.”

He speaks more of the elements of this hybrid audience:

I would hope adults would catch this idea of the fluidity of the border. and for children, my idea was related to the book Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions (Edwin Abbott Abbott). When you read it with naive eyes, it’s about lines and triangles, geometry. But when you read it again it’s about society’s borders. I was hoping this story would have this kind of double meaning.

Beyond Jorge’s personal family experience with the border and his observations, in person and on various media publications, he is involved with local projects that manifest this liminal space through individuals.

He’s working with people from borders living on the streets in Porto, such as “gypsy or Roma communities.” He discusses the way these realities can help to “open doors.” He feels that to “meet them where they are” he needs somebody who is both from inside their community and his own (Portuguese) to be a mediator of the liminal space. In a recent project, they created videos to help others on public buses understand the communities. The videos would be available on QR codes on the buses. This project called TAG empowers people from social housing to represent themselves.

“For instance, this was this tattoo parlor….A young gypsy girl started suddenly singing in the middle of the scene. But there had to be someone inside who is a bit outside who is able to [capture that and bring it to a local audience].” The man who was a part of the community was able to capture this scene and bring it to the public.

Liminal space in discourse

Jorge used to hear his PhD supervisor say: “Most dictators come from border zones.” He’s not sure if it’s true, but he finds that people who come from these “liminal areas” develop a strict mindset, perhaps as a kind of self or cultural preservation.

Jorge isn’t the only one asking us to imagine a borderless world in recent discourse. Due to population and birth rate shifts, climate change, and access to resources, others have called for a similar world despite a recent tightening and building of borders.

A recent Opinion piece in the Financial Times by Parag Khanna, founder and chief executive of Climate Alpha and author of Move, is called “Borders are holding the world’s eight billion people back” (11 November 2022). It concludes:

More habitable regions need to think about how to reprogramme themselves into an archipelago of centres for our future civilisation. This enlightened scenario urges us towards a world of demographic mobility combined with sustainable infrastructure.

The other scenarios on offer portend a neo-medieval world of warring fortresses, fending off at the gates those who both need and could offer help.

In other words, we shouldn’t assume borders (as we know them) are necessary for peace. In fact, they may procure the opposite. We also looked at borders a couple weeks ago in an investigation of a variety of mediums.

The way Jorge investigates these ideas through a parable allows our minds to go deep and wide in a philosophical exploration of the concept and back to its roots in human insecurities. In the story (and in life), humans are blindly creating divisions in sand, emphasizing the unnatural aspects of their existence. Children can grasp the elements of the story through experiences of play as well as the way they interpret both the natural and adult worlds. In fact, Jorge believes reaching children is essential to our future; once they are at university level, many students are already so rigid in thought that they cannot think differently.

What do you imagine for our future? If borders are “not natural” do they have any place in our world? How might we realize this utopic vision?

I’ll return to a discussion of borders in a month when I discuss the seeds of this newsletter and we’ll come back to ‘the border’ (or its obliteration) in other ways. I’d like to thank Jorge for joining me in this conversation and sharing his exciting work with us. I’m very curious where his work will lead in the future…and what will happen to the children and university students exposed to these exciting ideas before reaching a rigid understanding of our world.

You can reach out to Jorge or stay connected to his work through his website, Twitter (@PalinhosJorge), or via email: jorgepalinhos@gmail.com.

‘The beach is also liminal space.’

‘Liminal’ keeps popping up everywhere!

Maybe it’s the essence of poetry

What does it mean? (Really)

How do you use it? (Practically)

How do you catch it? (metaphorically)

Can you paint it? (Where in the spectrum does it fall?)

Questions within questions