13. Walls

How do artists use these boundaries to understand our divisions and connections?

Part of the ongoing series on Power and Perspectives.

“My first name, Jocelyn, was given to me by my grandfather because he says my dad was so happy when I was born.”

“Everyone called me Charlotte last year, but please now call me Charlie.”

“My last name is Hatziioanou. It’s Greek. Here, I’ll teach everyone to say it; repeat after me —”

“Sure my real name is Tze Wai, but I go by Rainbow. My kindergarten teacher gave me this as my English name and I like it.”

These are the sounds of my students’ voices, filling up the negative space of our classroom. At some point in my teaching journey, I took the second or third lessons of the year with high school students to share the stories of our names. Practically, it was a way to try to remember everyone’s name early in the year. But more than this, it was an English lesson and a way to value everyone in the room.

As each student shared a story, they began to engage in creating personal narratives as well as sometimes including etymology or cultural identity references. All responses were guaranteed to be unique; there were no: ‘I like that sport, too’ or ‘same thing’ or ‘she already said what I was going to say.’ Instead, we all took time to listen to what this person wanted to tell us about their name, whether a first, last, middle, or nick-name. By doing so, we started to create trust and to really listen to all the unique voices.

I always began as example. My first two names — Kathleen Clare — were connected to my grandmother but also told part of the story of where my family was from (an American with English, Irish, German, and French roots). But Waller, well, I had made that name into an anecdote of experience.

I wasn’t completely sure, but imagined that some ancestors on my English paternal side must have made walls. Those beautiful stone sculptures lining much of the countryside there as well as in my native New England. In any case, these walls fascinated me and one year I decided to learn about them from the inside out.

So I found something. It wasn’t a course on wall building in England. Instead it combined my loves for France, food, and craft into something really amazing. I found out about an NGO called La Sabranenque, sadly unable to stay afloat during the pandemic, that renovated and rebuilt medieval castles in France. Their project at the time was in Saint-Victor-la-Coste, a small village near Avignon with vineyards and other chateaux.

One July, I went to this place for two weeks to learn the craft and open myself to whatever else it had to offer. We slept in small stone huts they had created, listened to the cicadas in the hot sun, and ate fresh Provençal food each day. Each day, we left in the vans to the building site where we learned how to create walls, pathways, and stairs all out of stone. We learned the ways to use the natural beauty of the rocks both as geometrical puzzles and mediums of art.

We were worn out from the heat, the digging, and the lifting. Somehow the physical labor enhanced the experience of creation. Group members had different strengths, and the professional stone masons helped each one to differentiate the tasks. Together, we created beauty. But it was the act of creation that was also beautiful.

For some reason, these two weeks gave me a lot to think about. In addition to the stone work, I also learned some local cooking, wine production, and how to scale a castle wall (albeit not a very tall one). I’ve written about it before, in relation to the 5 paragraph essay and in my first novel (pp. 6-14):

Without much direction, she attacked relentlessly with the pick ax, finding strength from the breakfast of simple yet plentiful bread and butter with large bowls of coffee poured from Italian carafes. The mere motion of the stone mason’s flat hand like a mime over the production he expected gave her simple guidance. Her working space slowly cahnged shape, creating a slope she had already formulated in her mind. Its appearance was a moment of déja vu. Later, she noted that this was like the work of great sculptors. Michelangelo knew how to chip away at a beautiful piece of expensive marble. He had already imagined what it would turn into.

…

The work continued by selecting long, stable rocks with flat faces, like molar teeth long with pointed roots. The stone mason would systematically pull rocks neatly placed by the volunteers. As the sun rose toward its noon placement and breakfast was longer in the past, patience wore thin. Even Catherine thought many of these extractions unnecessary. A furled brow told her otherwise. The apprentice occasionally swore as he took out a series of fittings, avoiding eye contact with the volunteers as he concentrated on swiftly remaking the area. With his shirt tied around his dread locks, the others could see ripples of back muscles engaged in this process. ‘Merde! Touristes!’

More difficult than extracting, these bones of the earth had to be fit together in the hopes they would rest side by side for centuries. We assume our descendants will want to hold onto the history we are so deeply trying to restore. So far in the past, so deep into the future, as the sweat, dirt, and rock mix with the energies of the present.

These walls had functions from the start but they were also things of beauty. Safety, protection from the elements, protection from animals (or violent people!), long lasting…but not forever, as we found out through our reconstruction efforts.

Politics of space

There are many ways to think about space and many spatial theorists who offer their ideas. This will be a continuing theme as we look at the idea of ‘the city’ as well as various locations and spaces in the future. For walls, we often think of them as designed to demarcate or hold something up or back or in. It is something that helps us relate one space to another.

We can, for example, consider the politics of space through Michel Foucault’s frame or more practically look at Gaston Bachelard’s breakdown of spatial symbols and codes, although it also relies heavily on the imagination. Foucault looks at the matrix of power and knowledge (and desire) throughout our spheres and the way we are thus contained and controlled or let free. A short interview begins to discuss these ideas in relation to architecture. This article by John Allen is also a good starting point.

Bachelard looks at “corners” in The Poetics of Space (1958) as “half-box, part walls, part door” (p. 137). He discusses memories of moments at corners being those of “the silence of our thoughts…why describe the geometry of such indigent solitude?” (ibid). Being cornered is different from being up against a (flat) wall. The latter implies there is some sort of mental hurdle that we must learn to leap over. The wall presents more hope for escape as well as the possibility of meeting someone at the wall, less likely to occur in corners. Just as a corner might provide solace or danger (with nowhere to escape), a wall might be a barrier or a marked threshold of a figurative or literal journey and it might be the space of coming together as much as one of separation.

David Harvey, a prominent spatial and Marxist theorist whom I mentioned a few weeks ago in the context of the city as text, explores two main ideas of relational space in Social Justice and the City (1973):

The view of relative space proposes that it be understood as a relationship between objects which exists only because objects exist and relate to each other. There is another sense in which space can be viewed as relative and I choose to call this relational space—space regarded, in the fashion of Leibniz, as being contained in objects in the sense that an object can be said to exist only insofar as it contains and represents within itself relationships to other objects. (p. 13)

Walls then, as well as other types of boundary objects, are in the first sense essentially forgotten and only looked at as a way for one piece of land or one room of a house to relate to another. In the second sense, the wall becomes the space of knowledge and meaning.

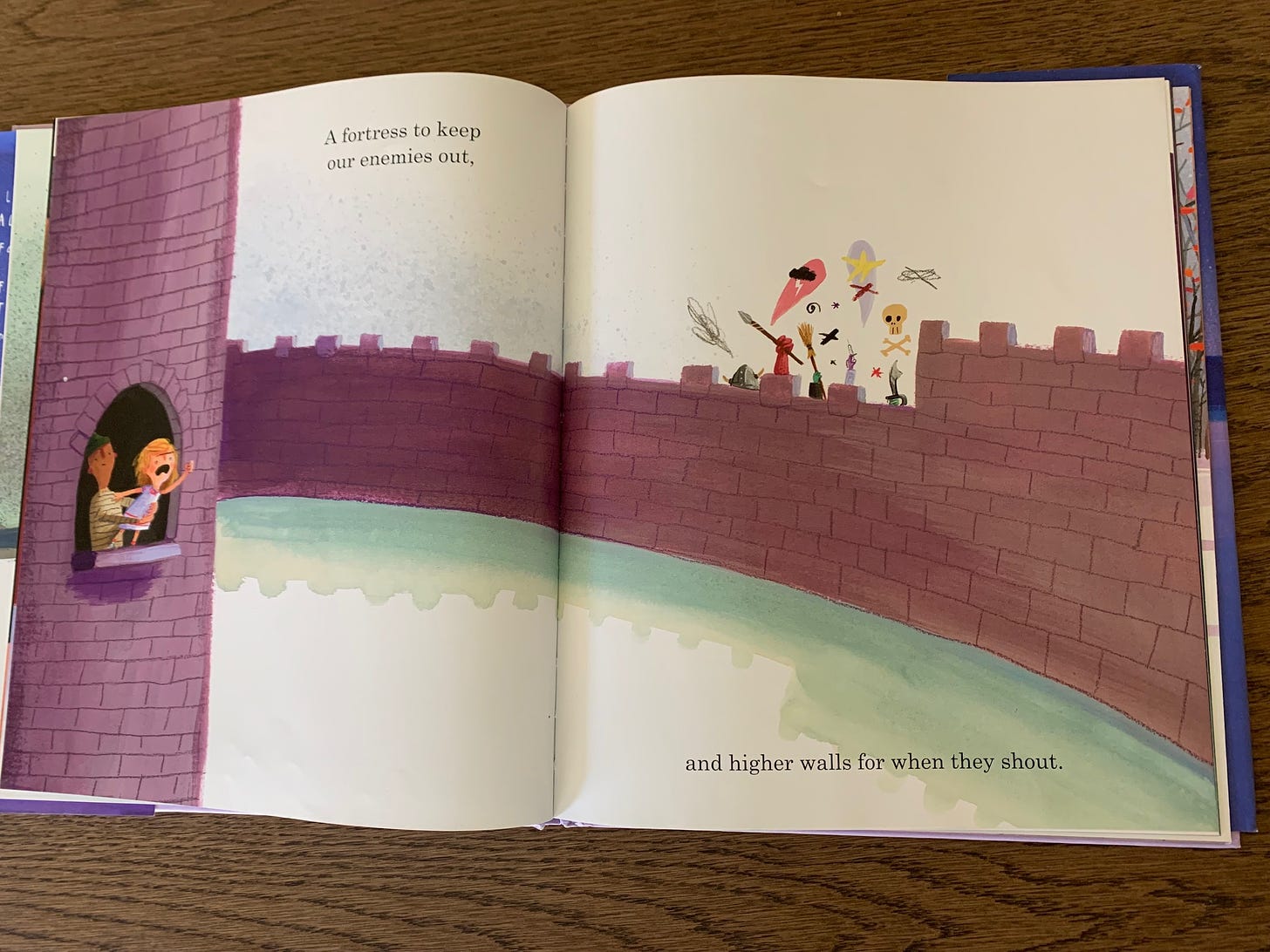

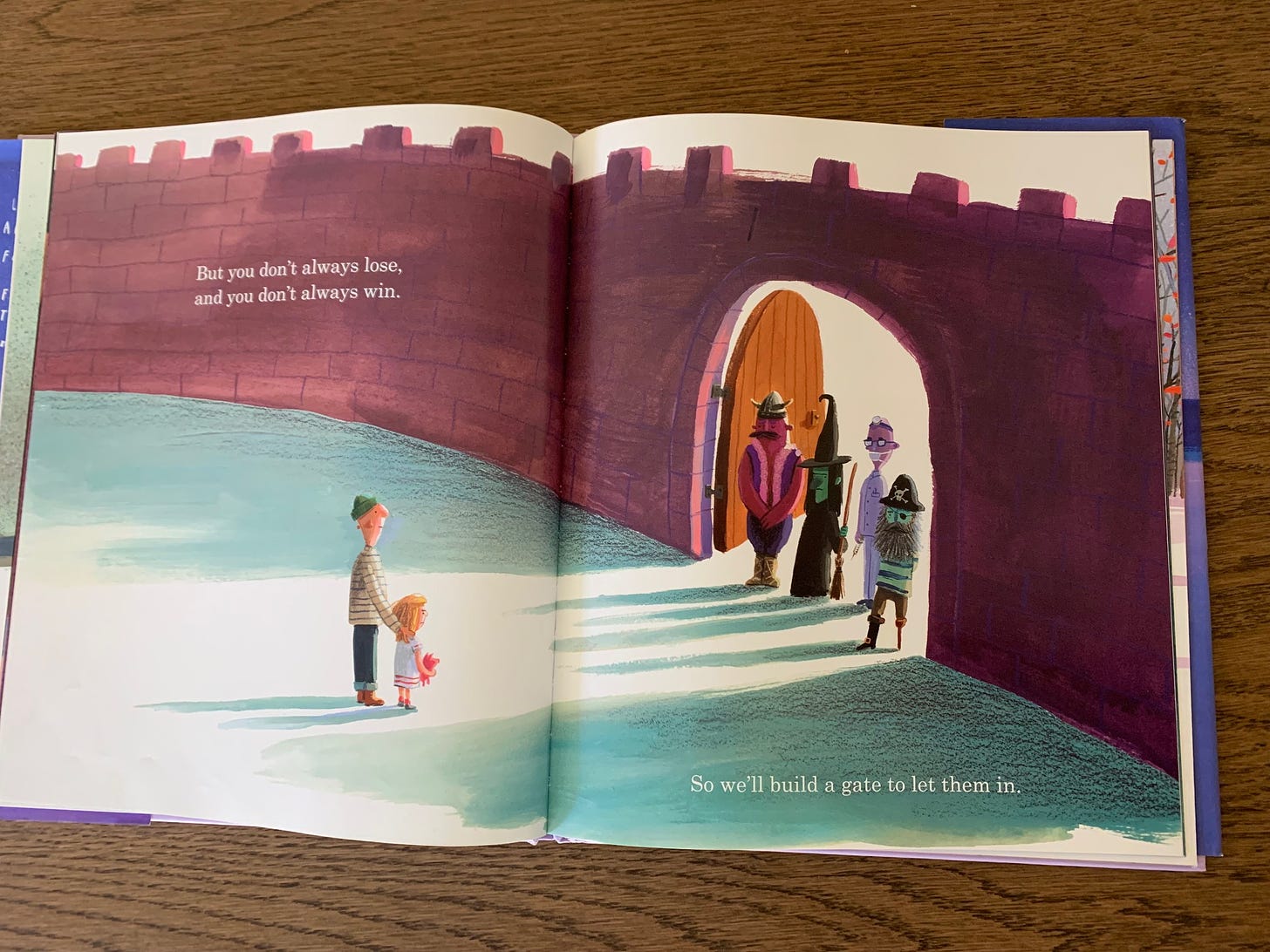

There is a wonderful children’s book by Oliver Jeffers called What We’ll Build (2020). Essentially a dad and his daughter have a toolbox to build their lives together, but the shapes of the buildings are secondary to the idea of building love, not only between each other but with others they meet on their journey.

At one point, they imagine building “A fortress to keep [their] enemies out, and higher walls for when they shout.” Danger is depicted just over the wall. The faces are hidden, showing that sometimes we are afraid or angry simply because we don’t know. However, the wall doesn’t last long: “But you don’t always lose, and you don’t always win. So we’ll build a gate to let them in.” When face to face, everything changes. What ensues is a tea party of apologies.

The wall is a marker of relationships between things and characters. It is only a block that at first seems threatening, but it is also the only reason these eccentric characters have come for tea. The containment of space and the father and daughter, makes an imaginary place of discovery.

Isn’t this like the forts of pillows or snow that we all make as kids? Sure, we want some time alone, but don’t we also want someone to come knocking (preferably with a snack)?

New England stone walls

Castle walls are decidedly impressive and clearly created for the purpose of safety. Many have little holes for archers to point their arrows at the enemy. And most that still exist with walls now have a permanently open gate. What about other walls that were never so ominous in nature? What purpose do they have?

Stone walls in England and New England were made to mark territory and to hold livestock. They were not tall enough to have much effect on human movement, other than as suggestion. Here you can read about the history, science and poetry of New England’s stone walls (as pictured at the top).

“Mending Wall” by Robert Frost uses this type of wall as its subject. All of Frost’s poems contain layers and nuances of meaning; unfortunately sometimes the ‘fame’ of their appeal makes us recall a simple line without context. “Good fences make good neighbors” is a line spoken by only one of the characters here, and one that has to be unpacked a bit more.

Here is an excerpt from the middle of the poem:

...The gaps I mean,No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

OR summarize above - that once a year they meet at the wall and look for damage to repair

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn't it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

This poem has been taught in high schools for many decades. Back in 1943, Mary Houston Davis and Elizabeth Lamar Rose wrote about this poem in The High School Journal: “Robert Frost's ‘Mending Wall’: A Lesson in Human Understanding,” which partly deals with helping students to understand the different voices here. They focus on nurturing ideas of community and “intelligent cooperation with other people who share our dreams” (p. 72).

How we see a text is everything. If these students are given powerful frames of understanding, how might they ‘read’ the news? A celebrity post? A revolutionary rap?

Like all of Frost’s poems, there is ambiguity in the meaning. Frost in part delivers this through the use of two subjective humans in the poem: the persona and his neighbor. He reminds us of that subjectivity (and his persona’s awareness of it) with phrases like, “it seems to me” and “I wonder.”

Baron Wormser writes of the poem’s misinterpretations in “ROBERT FROST AND THE DRAMA OF ENCOUNTER” (2011):

A friend recently told me of driving along and hearing on National Public Radio an Israeli settler explain that the wall separating the settlements from Palestinian areas was a good thing because the poet Robert Frost said, "Good fences make good neighbors." My friend pulled his car over and began pounding the dashboard and shrieking, "No, no, no!" I would have shrieked, too.

Although despite the oft quoted line about “good fences,” part of the point of the poem is to question the necessity of the wall, it is also the thing that brings them together each year and brings them into conversation. However, the space of “mending” is somewhat arbitrary. Why not leave the “gaps” in the wall that do not threaten either man’s crop? Why not meet for discussion with coffee instead?

Wormser also points out that Frost crafted this poem in England at the dawn of World War I (p. 80). Therefore, the implication is that Frost was in fact more critical of the nature of divisions; perhaps wondering instead why we could not let our barriers down, like the WWI soldiers in Joyeux Noel (Merry Christmas, 2005) who fleetingly allow themselves to find connections with each other as they emerge from the trenches for one day of celebration.

But Frank Lentricchia rejects any idea of political allegory in “Experience as Meaning: Robert Frosts's ‘Mending Wall’” (1972). Instead, he suggests that the poem is about what it means to be human and to allow one’s imagination to create meaning:

It is a poem that celebrates a process, not the thing itself. It is a poem, furthermore, that distinguishes between two kinds of people: one who seizes the particular occasion of mending as fuel for the imagination and therefore as a release from the dull ritual of work each spring and one who is trapped by work and by the past as it comes down to form of his father's cliché. (pp. 10-11)

I’m not certain his reading and the previous one are mutually exclusive, but it’s interesting to understand the poem as a space of human discovery.

Perhaps Frost is not asking for the wall to be completely erased, but to be permeable, like ideas and theories we may form in our minds. If this were the case, he would be making a case for internationalism rather than cosmopolitanism (an erasure of borders) or, clearly, fortified divisions. However, it is important to also understand the perspective of the neighbor who relies on his father, perhaps standing for tradition…why can’t he see beyond this? What is he afraid of?

If we consider a fence as a type of wall (as the neighbor in the poem does already), anyone else growing up in the 90s might recall Home Improvement. There was that neighbor named Wilson…we never see his face. It made it a bit of fun, but also perhaps commented on the nature of the neighbor relationship, each with their own space and lives, but able to help each other out at the relational space of the fence.

In literature, we might also look to other texts that include ‘wall’ in the title. Jean Paul Sartre’s “The Wall” (Le Mur, 1939) is a short story taking place during the Spanish Civil War. The wall is the space within the prisoners are held. It is also the place of execution, and the prisoners imagine wanting to jump back inside the wall for protection. It emphasizes the arbitrary nature of allegiances and space; since the wall’s signification quickly moves between imprisoner, murderer, and savior.

Virginia Woolf’s “Mark on the Wall” (1921) is also a modernist short story, this time from just after World War I. The protagonist sees a mark on her wall and allows her thoughts to travel, stating that “there’s no harm in putting a full stop to one’s disagreeable thoughts by looking at a mark on the wall.”

It seems the not-knowing (in part by purposefully not approaching the wall) is a reflection on our understanding of our world during a time when it all seems flipped on its head (WWI):

No, no, nothing is proved, nothing is known. And if I were to get up at this very moment and ascertain that the mark on the wall is really–what shall we say?–the head of a gigantic old nail, driven in two hundred years ago, which has now, owing to the patient attrition of many generations of housemaids, revealed its head above the coat of paint, and is taking its first view of modern life in the sight of a white-walled fire-lit room, what should I gain?–Knowledge? Matter for further speculation? I can think sitting still as well as standing up. And what is knowledge?

In fact, the mark is a “snail,” pointed out by her husband when he asks if she wants the newspaper, but notes: “it's no good buying newspapers.... Nothing ever happens. Curse this war; God damn this war!... All the same, I don't see why we should have a snail on our wall.”

The snail is a type of survivor as well as a mark of the absurd. Its slowness may be the retreat from reality’s harshness that the protagonist craves. In any case, the wall also becomes a relational space, filled with signification from the woman’s thoughts. The wall keeps her (and the snail) away from war and able to think freely.

Street art

Interior walls are private spaces of reflection; what about exterior, public ones? How can we talk about art and walls without looking at street art? I’m not going to do a ‘Street Art 101’ here, and, of course, street artists don’t always work on walls. You can see a few highlights on this list or this one if we were to make such an investigation together. I’ll try to weave more into my other posts and please add your favorites to the comments under any topic.

There are also many films on the topic, such as Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010), which you can view in full on Youtube.com. Although, it’s not really about Banksy but about Thierry Guetta, a French immigrant in Los Angeles who’s obsessed with street art. Guetta films everything, which brings up a lot of questions about the blurring of art and reality. A series of strange events connects Guetta and Banksy through a variety of art forms, also bringing up questions around professionalism of artistry, monetary value of art, and publicity/culture/fandom. It is first in this list from Widewalls of the “10 Best Graffiti and Street Art Movies.”

But I am also fascinated by a film from Agnès Varda called Murs Murs [Walls, Walls] (1981, France/USA) that explores unknown street artists in Los Angeles. Perhaps because she documents the earlier days of street art. Contemporary graffiti began in the 1960s, emerging from subcultures asserting their identities. These huge outdoor spaces would make invisible people visible. They were also cheap or free spaces to paint, as opposed to exhibiting in exclusive galleries.

The use of walls in this way is a kind of reclaiming of space by artists as well as by particular groups (you see this with ugly tagging, too — is it simply a cry for help? Look at me…this is mine…rather than a meaningful way of reinterpreting a space…). Whatever goes on an exterior wall immediately becomes public, even if it is later erased. The power of its presence is already an act. And, in a way, it is taking over state power; it is a type of antidote to surveillance. Instead of simply being watched we are all able to do the observing and able to think through these observations, rather than those with money and/or time to visit art galleries.

As a French filmmaker in LA, Varda arrives as an interested international journalist/artist, rather than an other-American. She is an insider with the subcultures she meets simply because she is foreign (as many of the street artists she interviews are) as well as being a groundbreaking female filmmaker. One of the themes running through the work she views is the depiction of marginalized peoples on the walls in gigantic forms that cannot be dismissed.

One male artist, Kent Twitchell, who was commissioned to paint unemployed people, chose real local artists as his subjects (technically unemployed, he says). The two women he selects are intentionally placed on the periphery to show they are marginalized even more than the male artists in society. (Some photographic representations of the mural even cut the women out, sadly emphasizing Twitchell’s point.)

She also looks at several artists working within the Chicano Movement. I only learned about the artistic element of this movement and revolution in my early teaching days when I decided to teach some Rage Against the Machine lyrics as poetry in a civil disobedience unit (“This is for the people of the sun…” - check out all the walls in the music video). (It predated seeing them live for the first time outside of Milan in an awesome politically charged concert…in the last years of W, whom they definitely had something to say about.) Lead singer Zack de la Rocha’s father was a member of Los Four, a group of Chicano artists whom you can read about in an article from Walker Art Gallery.

Some of the artists Varda speaks to were either in gangs or sought out art as an alternative to violence. The images are sometimes violent themselves, either surreal or very realistic. But others simply want to show Chicano faces, like Judy Baca who says she had never seen people like her in art galleries.

Similarly, a Black female street artist named Suzanne Jackson tells Varda that the Black Panthers had asked her to paint “fists and rifles,” but she preferred flowers and birds, “other symbols that are really necessary,” on her murals. Huge ones. If you want to check them out, the Mural Conservancy of LA has photographs as well as maps of her street art and several others highlighted in the film. Partly she is simply interested in the aesthetic and partly she wants to show this part of her identity as a Black woman…one of beauty, and one that that is hugely visible as a mural in LA. The aesthetic is also of interest to Varda in terms of the light and color of LA. Artists discuss the light and weather in relation to the beauty of the art they are able to create on the streets, despite some of the ugly violence and poverty and racism that coexists with that beauty.

Spatial justice & painted walls

The way street artists use space is a way to challenge a constructed public space and change the dynamics of power. Spatial theorists work in an interdisciplinary fashion to understand the relationship between space, justice, culture (& ‘the city’, as discussed a few weeks ago). Edward W. Soja’s Seeking Spatial Justice discusses the changing nature of LA with implications for “anthropology and cultural studies, law and social welfare, postcolonial and feminist critiques, theology and bible studies, race theory and queer theory, literary criticism and poetry, art and music, archaeology and international relations, economics and accounting” (p. 14). He discusses this perspective as having an effect on our understanding of epistemology. LA street art could be an extra chapter in this book, drawing on the ideas of subcultures, gentrification, and labour movements that he discusses.

Henri Lefebvre (i.e. The Production of Space) and David Harvey (i.e. Social Justice and the City as discussed above) are other go-tos in this area of research. An interesting article by Andrzej Zieleniec explores the way Lefebvre’s work can be applied to graffiti. In “The right to write the city: Lefebvre and graffiti,” Zieleniec “read[s] graffiti as a means for reclaiming and remaking the city as a more humane and just, social space.”

In a newsletter on Portraits later on, I’ll take a look at Varda’s follow-up quasi-real film called Documenteur, where “a woman played by Sabine Mamou (an editor on both films) is seen wandering numbly around Los Angeles, visiting some of the murals from the first film as she tries to pull herself together after the breakup of a marriage” (from the NYT review of Murs Murs in 1981, paywall). In this way, she explores the effect of LA’s street images on an individual rather than their roles in larger political shifts. Harvey discusses the way that “Marxian ethics” in regards to spatial theory teaches us that “concepts of social justice and morality relate to and stem from human practice rather than with arguments about the eternal truths to be attached to these concepts” (p. 15). There is a sense that the everyday experience, then, of these painted walls by humans (like the fictional Sabine) is what is most important. How do they change the way we see a neighborhood? A group of people? Ourselves? How might they make us smile or pause or reflect?

In this same vein, let’s also look at the artist Shamsia Hassani from Afghanistan. I was teaching a sixth grade art class last year and from a long list of painters new and old that I bombarded the students with, she was their favorite, almost like an art hero. Hassani makes beauty and she challenges not just patriarchal views but those specifically of the Taliban; simply her act of creation is a threat to their existence.

Hassani was also an art professor at Kabul University until she was forced to exile her country after the Taliban takeover in 2021. She told The Guardian:

My country and my art gave me an identity. The day Kabul fell, I could not believe it; my heart was on fire….Art was evolving there. The number of artists and art lovers was gradually increasing. Of course, there were still many who opposed art, but it was available for everyone and we had the freedom to be an artist. We had planted a seed and were watching it grow.

For her, walls were the perfect place to make art accessible to all. However, the public nature of creation was also at once a potential danger to herself and political act of defiance. Creating beauty, too, from the war torn walls was a method of reclamation. The damage becomes part of the art, part of the beauty.

How can we reclaim the walls that are also within ourselves? Can our own damage — or traumas — be re-signified through art?

This style and reclamation of space is also on many political border walls, and we’ll take a look at a few in the next newsletter on Borders. Next month, I’ll also share an interview with professor and writer Jorge Palinhos, who recently wrote a parable about (border) walls that was turned into a theatre production. In a still later post, we’ll also look at Walled Cities, places I love to visit and consider the cultural effect of erecting, living within (or outside of), and maintaining these walls. But I only love them because their gates are open.

Please consider subscribing or sharing this post if you enjoyed it! Even free subscriptions help this project to grow.