14. Borders

How does artistry of and at the border change its impact on individuals?

Part of the ongoing series on Place and Ethics.

“Build the wall! Build the wall! Build the wall!”

So goes the chant of the fear-mongering politicians keen to use billions of dollars for a dangerous wall instead for, say, healthcare or schools. For a bit of (terrifying) fun, you can read “Trump’s Evolving Words on the Wall,” an NYT compilation of Trump tweets, speeches, and interviews. It exposes a lot of ridiculousness but is also slightly traumatizing that a president could be so…uninformed (understatement and euphemism). And it’s also scary because the wall is still being built.

It’s not only in the US. Poland has built a wall between themselves and Belarus in the past year and Greece is tripling the length of its Turkish border wall. “The world is witnessing a rapid proliferation of border walls”:

[T]he post-Cold War evolution towards a global village was a delusion that lasted only a decade. The reterritorialization of the world and its delineations made a comeback, and in the years since borders have become gradually more demarcated as well as harder, reinforced, more fortified, and better armored. They have morphed into symbols of states’ entrenchment behind ramparts designed to address asymmetric, unconventional, and global threats, including unwanted flows. Once supposedly antiquated, walls have become gradually normalized solutions to geopolitical tensions and remedies to the instability generated by an unbalanced international system.

Building walls to contain or keep out people is something that just doesn’t make sense (except for maybe actually dangerous criminals until and if they can be rehabilitated). I’m just as afraid of terrorism as the next person, but I wonder if these walls really have any effect on it…or if they do, are they just patching up the problems rather than getting to the root?

The movement of people between nations is a complicated one, but I would argue it doesn’t have to be. So much is about fears. The border walls show us those fears and heartbreak viscerally.

Permeable border walls aren’t a bad thing, though. Marking a passage from place to place may help us to experience the crossing of a threshold in a meaningful way. Without a clear welcome, we may feel more alienated than anything. And walls may practically allow for processing: providing support and nourishment; sharing ways to learn the language; not allowing tagged criminals to pass through.

Of course, this is problematic when power decides who can cross. Who is a criminal? Are you a criminal for writing a book about an oppressive regime? For whistle blowing? For stealing bread for your family? For trying to cross without the right papers?

My US passport gets me privilege at borders. Nearly any border crossing is open to me. Maybe I have to pre-register and hand over some cash. Fine. But I can get there, usually. I can’t always stay, legally, without a visa for a job. For this reason, I would love a Swiss passport in a few years and I’m slowly working on the German to get it. Brexit has made my husband’s British passport less valuable. But we can both cross. Anywhere.

I fully realize the same isn’t true for everyone. And mostly I just think: what the fuck?

I’m not going to go into all the details of border crossing and laws. A good overview of the history of these walls and their current state is linked to the initial quote above from the Migration Policy Institute. You might also check out this new fact-based graphic novel called: Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, recommended by The Economist and others. I did a lot of research about this topic in the US and Hong Kong. If you’re interested especially in films dealing with this idea in those two cities, you can read about it in my project or just check out the bibliography with a huge list of beautiful films. The research I did enabled me to participate in conferences like The Network for Migration and Culture: Migration, Memory, Place (Copenhagen, 2012) and Societas Ethicas: Ethics and Migration (Sibiu, Romania, 2012) that helped me understand the bigger picture more deeply, especially on the level of cultural identity.

And that’s the focus today, too: how do the arts at or of the border make a dialogue of ideas about it? How do they affect individual identity and collective culture? How are different borders the same and unique? How are they experienced differently by each individual? How do borders become meeting places of experience?

Today we will take a look at a few artists working with or at this space after a quick look at theorizing this border space.

Theorizing the space of the border

Walls are a visible form of control; but art is also a visible form of rebellion. Art on some of these border walls resignifies the meaning. But they can’t change the purpose, except for, perhaps, making them also meeting points of conversations about change and places of mourning.

Even if one crosses through a border, it can have meaning in and of itself. Moving through a threshold like this will mark different things to different people. Practically: it’s different on the other side. Culturally, maybe legally. Our open Schengen borders here in Basel with France and Germany were mainly closed during COVID, save certain workers or split families. Even after they began opening, there were differences: when and where to wear a mask (and what kind), new documentation like vaccine passports, and sometimes registration and quarantine rules. These have now been obliterated, but we still see and hear differences over the borders: fashions, languages, ways of greeting, the way a bakery smells, quality of public bathrooms and parks, prices of groceries, currencies. Some of these are practical or economic, others are cultural.

On the other side of Switzerland, I wrote about skiing between the Swiss and Italian borders at Zermatt and the Matterhorn (where this publication gets its name). Ultimately, the crossing over allows us to play with our own identities through culture. In my view, one should be allowed to have this space of play and to share their own culture(s) with the other side.

Jacques Derrida’s The Truth in Painting (La verité en peinture, translated from the French by Geoffrey Bennington and Ian McLeod, 1978) is a beautiful text about the way we understand our world through frames; it’s also about looking at a painting and the way Cézanne may have viewed truth in a letter (pp. 2-4). You can think of the border like a frame and a threshold of entry. This is how we enter viewing a painting, through its frame first. The same is true of a written text: the title is a frame (the title of a painting is also an additional border). What happens at this point of entry?

The book is a great entry if you haven’t read Derrida (the founder of deconstruction) before. There is an online pdf of the English version available here; look especially at “Parergon” circa p. 54.

Each painting has a “frame, title, signature, museum, archive, reproduction, discourse, market, in short: everywhere where one legislates on the right to painting by marking the limit” (p. 11). The layers of borders around the painting change the way it is viewed and who is allowed to view it. Similarly, when we think about crossing the border, there will always be differences of frames in the way people see us or read us and vice versa. We should be aware of those layers, to some extent at least, so that we may assert our own (cultural) identities within them and in relation to them.

For example, ‘illegal’ immigrants live in an invisible kind of space, a liminality of existence that is constantly in a hidden threshold they can never cross. They occupy the purgatorial space of not being here or there because they have somehow slipped through the cracks. Good for them (unless they are one of those very few real criminals, although I guess they would be dangerous on either side), but once they are there, what becomes of them? They are constantly fighting to find an accepted identity, legally and culturally. The article “Twenty-First-Century Globalization and Illegal Migration” explores this concept in depth (Katharine Donato and Douglas Massey, 2016).

A few other articles you might want to check out (and if not, just skip to the next section that gets into the art):

“On the Border: From the Abstract to the Specific” (Charles Tatum, 2000)

“Re-Thinking Margins and Borders: An Interview with Gloria Anzaldúa” (Ellie Hernández and Gloria Anzaldúa 1995) [“By looking more closely at the significance of borders, not only do we witness the rise of a border consciousness in US cultural reproduction, but we see how the process of "crossing over" problematizes all sense of identity” (p. 7).]

“Circular Migration and the Spaces of Cultural Assertion” (Vinay Gidwani and K. Sivaramakrishnan 2003)

“Border Crossing as Act of Resistance: The Autonomy of Migration as Theoretical Intervention into Border Studies” (Sabine Hess 2017)

“Migration-Facilitating Capital: A Bourdieusian Theory of International Migration” (Jaeeun Kim 2018) A little taste:

…existing conceptualizations leave little room for theorizing the fundamentally relational, political, and cultural processes through which various resources are turned into migration-facilitating capital of differing values, (re)producing inequality in cross-border mobility and in the distribution of related material and symbolic goods….

The Bourdieusian theory of international migration proposed in this article can reorient the sociology of migration in several ways. The emerging scholarship on “legal violence” (Menjívar and Abrego 2012)—partly inspired by Bourdieu’s conceptualization of “symbolic violence”—highlights the key role the state plays in producing “illegal” migrants, thwarting their incorporation, and legitimizing their symbolic denigration. Although a welcome development, this scholarship is limited by its exclusive focus on the receiving context,5 its generally draconian portrayal of state power, and its undeveloped theorization of the meso-level structure that mediates the encounter between state and migrants. (pp. 262-3)

Art on border walls (& the walls themselves)

Artists, mainly of or related to the Chicano Movement, working on the wall between the US and Mexico have made some beautiful and haunting images. There’s a good compilation on Culture Trip and the University of Pittsburg’s Panoramas. Artists make murals, like those of the Mexican tradition, and also document names and faces of those who have died or made a difference at the border.

Paseo de la Humanidad, in Heroica Nogales, Sonora, Mexico (2004) is a sculpture-mural made in collaboration by Alberto Morackis, Guadalupe Serrano, and Alfred J. Quiróz (photos in link; this LA professor has made a great website of art at the border):

Alberto Morackis once explained that the name of his and Serrano’s art workshop, Taller Yonke (junkyard workshop), originated from the “many junkyards in Nogales (Mexico), and because Mexico is the United States’ junkyard.” The duo’s next work in 2004 used scrap metal to vividly illustrate the nature of the uneven and conflicting relationship between the U.S. and Mexico in Paseo de la Humanidad (Parade of Humanity). UA Art Professor Alfred J. Quiróz collaborated with Morackis and Serrano in bringing the colorful metal murals to life.

Lizbeth de la Cruz Santana is a muralist and writer who has done a lot of work at the border, usually depicting individuals, like the above mural. Santana discusses the inability of split families to even see each other as an explanation for painting murals of deported individuals. Her work humanizes the experience and invites others to participate in an understanding. She is currently studying to earn a PhD with a focus on digital storytelling, so I imagine the dialogue will move more accessibly to digital platforms as well.

Ana Teresa Fernández (above) took a different approach by painting the border wall a similar color to the background, effectively making it invisible in “Erasing the Border.”

The West Bank Wall is also a space where artists actively engage with political and human ideas through paintings. Because it has been used by international artists as well, it brings up the question of belonging: whom does the wall belong to and who has a right to give it a voice? Bahira Amin summarizes:

Many Palestinian activists object to international artists who come to Palestine for a 'spraycation' - using the wall as their canvas for easy points for progressiveness on social media, while enjoying their privilege of leaving when they're done. Their art, some argue, also normalises the appearance of the wall, mainstreaming instead of highlighting its injustice, as most artists seek to do. On the other hand, work created by Palestinian artists can serve as both radical reminders of resistance and messages of hope for the Palestinian community, especially since the art is on the 'inside' of the wall (the side facing the West Bank).

The paintings can also come with consequence, as in the case of the Italian muralists behind Ahed Tamimi’s visage who were then detained by the Israeli government. The teenager was jailed for attacking an Israeli soldier and became a symbol of the Palestinian activism.

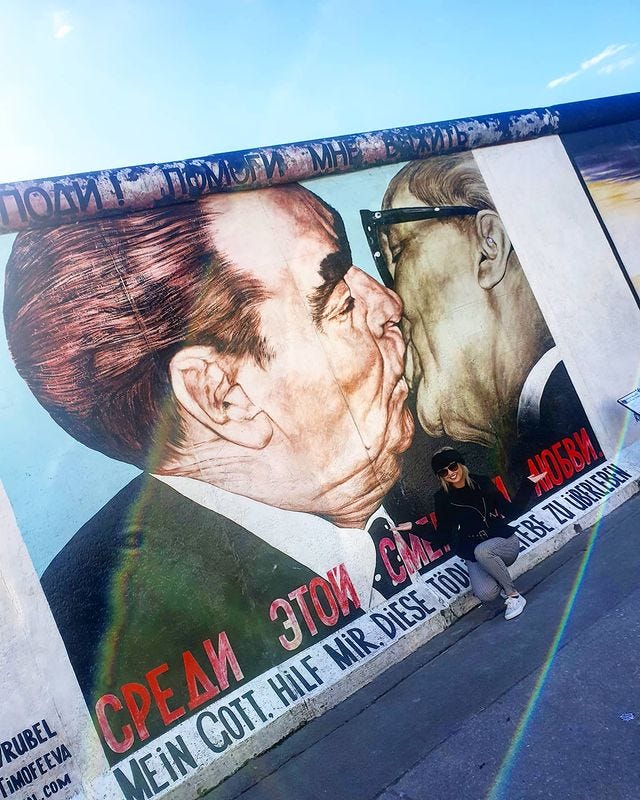

The Berlin Wall was a unique place of division; built in the middle of a city, dividing two completely different regimes, histories, and types of power, but also dividing the whole world. Something unique happened at the Berlin Wall after it fell. By not completely falling, but being reimagined, we can continue to come to the threshold to try to understand it:

The Berlin Wall, once a symbol of division, now forms a large open-air gallery featuring 105 murals by artists from across the globe. Many were painted in 1990, the year after the wall fell, and the artworks that line the banks of the River Spree stand as a memorial to the reunification of Germany and to a broader moment of globally significant political change.

Capturing the migratory threshold

There is also art that uses border walls within their films or paintings to create a narrative and different perspective. Partly these pieces make the walls more visible, elsewhere.

Cycling the Frame is a documentary by Cynthia Beatt starring Tilda Swinton who roams around West Berlin near the wall in 1988, just a year before it came down. She starts and ends at Brandenberg Gate, moving down paths that look like the countryside and stopping for wine or tea near signs that threaten danger if you were to cross. She says there are “gardens everywhere…[and] birds, horses, families…strange things [to see] in cities.” An early long pan of the ugly cement wall is juxtaposed with wooden fences surrounding idyllic green spaces. The sounds we hear are of the birds, horses running, the rain, or the bicycle itself. Swinton says: “I wish they’d built the wall out of trees…at least it would still be alive.”

The wall as subject has an eerie presence. Swinton (and Beatt) are empathetic to those on the other side but can’t really imagine it there. Across the water, it looks uncannily like-Berlin-but-not. The arbitrary nature of its placement (and presence) is another implicit theme. In a place with so much natural beauty, one wonders what is being separated, what went wrong? Of course, we all know historically what went wrong on a macro scale, but the impact on day to day life as well as the cultural elements of day to day life that allowed it to happen in the first place are emphasized here. How could evil come from this space? What have we done by taking power over places anyway?

Francis Alÿs is an artist who works with borders frequently. The Belgian artist has done work in Afghanistan, Hong Kong, Iraq, Brazil, and other places, often working the with border or with refugees to create his art.

Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic

This is a quote from the artist about his work at national borders. His walking “Green Line” of paint in Jerusalem (2004) was made to be somewhat of an “absurd” act, although recalling history. His action was ultimately done to create a reaction from others; in other words, the art is the reaction:

Using green paint, Alÿs walked along the armistice border, known as ‘the green line’, pencilled on a map by Moshe Dayan at the end of the war between Israel and Jordan in 1948. This remained the border until the Six Day War in 1967 after which Israel occupied Palestinian-inhabited territories east of the line. …He later encouraged various commentators from Israel, Palestine, and other countries to reflect on his action, and their voices, sometimes sceptical, sometimes approving, can be heard while the video of his action is screened.

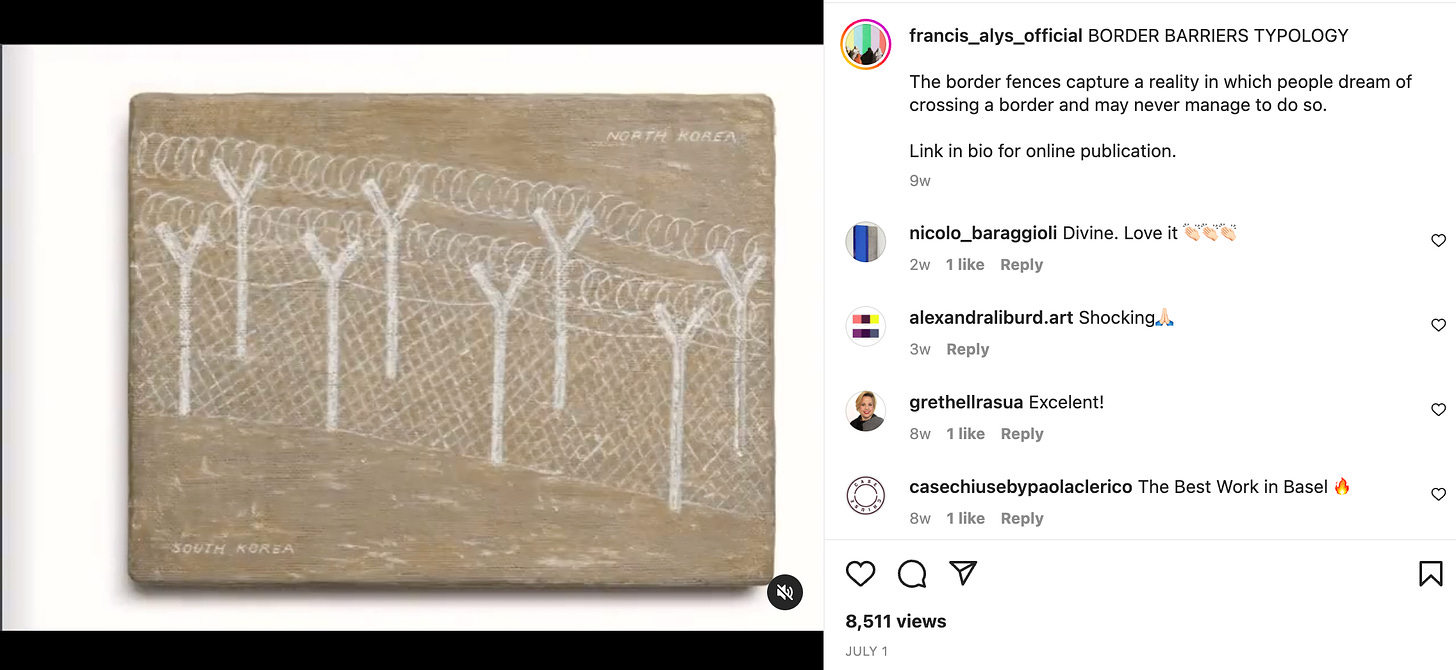

In my opinion, the most captivating piece at Art Basel Unlimited 2022 was Alÿs’ room of small paintings of various border walls, like the one above. The installation was called: “Border Barriers Typology: Cases #1 to #23, 2019-2021.” (The link allows you to see a few details as well as the effect of the whole room.)

Each very small oil painting was titled by place, but this seemed almost arbitrary, for there was an eerie unification among them through their similar act of separation and even violence as well as power. Like the one above, there are few clear markers of place. Rather it is the wall itself (and its barbed wire or other markers of hostility) that is the place. The one above is labeled “North Korea,” but the gallery website shows an almost identical painting labeled: “English Channel.” While we may think these places are eons apart in terms of ideology and human rights, Alÿs’ work suggests otherwise. It is as if the names point out the arbitrary nature of land ownership and control. What is this fence / wall in monochrome, often ominous looking even in its smallness, doing other than some existential experiment in power?

The gallery explanation tells us:

The paintings are based on Alÿs’s own sketches and archived photographs of closed borders from around the world, which he merged with his memory of each place. These fences have neither a beginning nor end; they are insurmountable and impenetrable, partly through barbed wire and partly through fine-meshed wire patterns. Despite the abstraction of these divided landscapes, the names of the regions in conflict, such as Afghanistan / Pakistan or Israel / West Bank, are written in capital letters in the lower-left and upper-right corners respectively.

His actual visits provide a layered understanding to the paintings. Though they appear simple, they are completed with some kind of authenticity. Because the paintings also came from “memory,” there may also be tricks of the mind at play; the invisible nature of fear and power at these walls can certainly play with our depictions of them.

Invisible borders

Does taking away the mark of a physical border also inhibit us? In some ways it may emphasize the arbitrary nature even further (like the case of the “green line” above).

I attended a lecture with Gwen Cressman from The University of Strasbourg at The University of Basel last spring (2022) that talked about this topic in border photography (link includes publication list). Cressman was focused mainly on the US-Canadian border during this talk, as a sort of antagonist to the US-Mexican border. Although less visible, this border could be as powerful, especially after 9-11 and a tightening of security (in general, but also specifically here, because there was a general belief that this is how the terrorists got in, even if it wasn’t true).

One artists she discussed was photographer Dennis Oppenheim who was working at the US-Canadian border in the 1960s and 70s. His work often used photographed natural landscape, such as cutting ice in concentric circles in the border space between Maine and Canada. He was playing with this division of land and asking us to look at the human effect on it more closely.

Andreas Rutkauskas also photographs this border’s natural landscape. However, in the twenty-first century, what appears to be an open border is actually marked by digital surveillance:

While my images do not depict U.S. or Canadian border patrols, many of the photographs were taken shortly before or after the encounters with these officials. Often within a short period of my arrival at these locations, and occasionally, even prior to my arrival, a field unit would be dispatched to investigate. After the officials got to know my intent, they would move the vehicles out of my frame, so I could make the shot. However, this process is only part of what leads to the appearance of the border being so permeable in my images. There are places where I did not encounter anyone while photographing, where I could walk for hours along the denuded cutline that separates the two countries without impediment. Even though security measures discourage humans from lingering at the Canada/U.S. border, they cannot fully monitor this vast territory.

This playing with space and law give the landscapes more meaning. There is an invisible possibility that the place is being watched by someone other than the photographer on the other side of the lens.

She also looked at other contemporary border artists, like Valerio Vincenzo, who photographed peaceful borders around Europe in this project, 2001-2019. Here is one example from his work:

Although the border is now peaceful and mostly natural looking, it provides a violent history, one that is a reminder of problems between two nations. Cressman speaks of b/orderscapes – landscapes created by the border.

These are all still borders even if they are less visible than the barbed wire walls of separation that divide families. But what about the border that continues invisibly beyond geographical boundaries? Don’t borders inhibit people through cultural representation or economic factors? If we are aware of these invisible borders, we may be more able to help the migrant to cross. Claire F. Fox investigates this in “The Portable Border: Site-Specificity, Art, and the U. S.-Mexico Frontier” (1994):

Today, "the border" and "border crossing" are commonly used critical metaphors among multicultural and postmodernist artists and writers. According to Chon Noriega, these terms were first employed in the 1960s and 1970s by Chicano and Mexican scholars to refer to the experience of undocumented workers from Mexico crossing to the United States.3 Indeed, in Chicano arts and letters, "Borderlands" has replaced Aztlhn as the metaphor of choice to designate a communal space.4 But even though the U.S.-Mexico border retains a shadowy presence in the usage of these terms, the border which is currently in vogue in the U.S., both among Chicano scholars and among those theorists working on other cultural differences, is rarely site-specific.5 Rather, it is invoked as a marker of hybrid or liminal subjectivities, such as those which would be experienced by persons who negotiate among multiple cultural, linguistic, racial, or sexual systems throughout their lives. When the border is spatialized in these theories, that space is almost always universal. "The Third World having been collapsed into the First,"6 as the argument goes, the border is now to be found in any metropolis-wherever poor, displaced, ethnic, immigrant, or sexual minority populations collide with the "hegemonic" population, which is usually understood to consist of middle- and upper- class WASPs. (p. 61)

Since the article is nearly thirty years old, Fox isn’t even talking about virtual borders. Instead, it is the border of identity, and the way in which we have tickets to entry within a culture or not.

Hostile Terrain 94 is a collective project exposing the dangers of migration, back at the US-Mexican border again, but in the invisible crossing spaces in the desert, before one even gets to barriers at the wall (or natural boundaries). From the website:

Hostile Terrain 94 (HT94) is a participatory art project sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), a non-profit research-art-education-media collective, directed by anthropologist Jason De León. The exhibition is composed of over 3,200 handwritten toe tags that represent migrants who have died trying to cross the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2019. These tags are geolocated on a wall map of the desert showing the exact locations where remains were found. This installation will simultaneously take place at a large number of institutions, both nationally and globally in 2021 throughout 2022.

Literary narratives similarly step away from actual borderlines and into a deeper ellipsis of understanding and perspective.

The recent novel American Dirt had a load of press both for its success and subsequent cancel due to the inauthentic voice (a non-Mexican writing a story of Mexican border crossing into the US). What do you think? Can someone imagine another’s experience? Should they?

I remember seeing novelist and professor Junot Díaz at a talk in Hong Kong discussing the way he likes to write from many perspectives, imagining a self as a different gender or race. Someone in the audience went to town with him and others, like Joe Fassler in The Atlantic, have critiqued him for a lack of authenticity and range when it comes to, especially, female characters. But I felt that his response was genuine: he was trying to understand and as a writer, you have to try on different identities. I guess it depends how the writing is used though. Are we able to contextualize it? Does the other also have a voice?

If you think American Dirt wasn’t Jeanine Cummins’ story to tell, the Texas Observer has a compiled a list of border crossing books by immigrants. Relatedly, The Guardian has a list of books about the Berlin Wall (some fiction and some not). And this article by Drew Paul looks at literature and film at the Israel/Palestine border.

Do you live near a (national) border? Does it change your relationship with your home? The space you occupy? Is it a threatening or a welcome border? Is it visible? How do you feel when you cross other borders? Do land borders, in particular, have a certain effect on you? Let us know, and certainly let us know if you have related projects that we can check out. We would love to hear your authentic voice!

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

Wow... there is so much here I feel like I need a good hour or so to sift through it. Which I don't have right now. Will have to return to this, and will certainly save it as a post. I'm really interested in borders too and how artists represent and process the issues they raise. Some other artists who immediately come to mind are JR and Christo and Jeanne Claude. I also wrote a post on this some time ago but for the life of me now I can't find it! Anyway, thanks for all this good stuff, really interesting.