The Saturday Brunch: a figurative flat white or fizzy to start your weekend

Before we get into haiku, I want to share a quick reminder about my upcoming lecture and discussion From Theory to Fiction on Tuesday (12:30 pm EST) at Pratt Institute (Brooklyn). You can register here for the Zoom event. All are welcome!

Today’s post is from a series on Art of Zen this month:

Introduction to Art of Zen

Next week, we’ll investigate meditation for creators

Haiku

Probably most of you have written a haiku at some point in school. It’s an easy way for teachers to introduce structured poetry and get away from the dreaded everything-must-rhyme ‘free’ verse that many kids start out with. (I love a good rhyme like the rest of you, but, man: the tree is big / I’m wearing a purple wig / and now there’s a twig / hanging on the…fig!)

Haiku are (seemingly) simple to create but can contain immense complexity. The concept is not dissimilar from the ensō. Like the ensō, let’s take a short look at the philosophy, history, and examples before diving in to create our own.

Haiku have these parameters:

three lines of poetry, usually consisting of 5-7-5 syllables (essentially, very short)

simple (yet vivid) imagery (of any of the senses)

specific events or observations (avoid generalizations)

present tense — as if we are in the moment with the poet

use of juxtaposition, often unexpected connections or oppositions

Haiku was adapted over three centuries from renga, “an oral poem, generally a hundred stanzas long, which was also composed syllabically.” Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694) was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk and is often called the founder of haiku poetry, which he perfected a century after its creation on a long journey after his home had burnt down. Although the basic parameters had already been set, he went deeper with his discoveries than others had before and published anthologies of his work.

One such anthology was called Spring Days and included this famous work:

Furuike ya, kawazu tobikomu, mizu no oto.

Breaking the silence

Of an ancient pond,

A frog jumped into water-

A deep resonance.

Which has also been translated as:

An old pond!

A frog jumps in—

the sound of water.

And here are a couple others from Bashō:

In the cicada's cry

No sign can foretell

How soon it must die.

In Kyoto,

hearing the cuckoo,

I long for Kyoto.

Notably, Basho wrote many of his haiku while traveling through the country. As we travel — whether to a new part of town or a new continent — we are bombarded with simple things made fresh or more complex through their minor differences. The shifts in foliage or style of potatoes people eat coupled with the varying smells of the earth or sea and differences in landscape or architecture give us new perspectives. As we notice simple things, we may discover epiphanies about ourselves, nature, or the universe.

Here are a few other classic Japanese examples of haiku:

The light of a candle

is transferred to another candle—

spring twilight.-Yosa Buson

A world of dew,

And within every dewdrop

A world of struggle.

First autumn morning

the mirror I stare into

shows my father's face.

Writing haiku has an essence that is much more than the poems themselves. They are about seeing, witnessing, and immersing oneself in the present. They are also about allowing small things to stand for big experiences, finding answers in the details of our lives.

Michael Dylan Welch writes about the “art of direct seeing” in Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which I previously mentioned in regards to turning 42 this past October. He writes:

Phaedrus overcomes one of his student’s blocks to writing by asking her to focus on Bozeman (at first she wanted to write about the United States). When she couldn’t write anything, the teacher asked her to narrow down her subject to Bozeman’s main street. Still no luck. He told her to narrow down her focus to a single building on Main Street, and to start with the top-left brick. Then voilá! Out came an essay!

This experience has plenty to do with haiku, and more importantly, haiku writer’s block. Pirsig explains: “She was blocked because she was trying to repeat, in her writing, things she had already heard . . . She couldn’t think of anything to write . . . because she couldn’t recall anything she had heard worth repeating. She was strangely unaware that she could look and see freshly for herself . . . The narrowing down to one brick destroyed the blockage because it was so obvious she had to do some original and direct seeing.”

Simple structures can help us to focus our creativity. In addition to the narrowing down approach in the book above, the limitation to short verse can help us to select diction that serves our purpose best and to think carefully about the placement of words. They are small treasures. A few words contain much — and perhaps contain different ideas for readers entering the poem with their own experiences or even current moods.

Pirsig was familiar with the reinvention of the haiku by American beat poets, especially Jack Kerouac. Of course, he was also famous for the journey, like Bashō, due to his novel On the Road. Kerouac describes it as such:

The American haiku is not exactly the Japanese Haiku. The Japanese Haiku is strictly disciplined to seventeen syllables but since the language structure is different I don’t think American Haikus (short three-line poems intended to be completely packed with Void of Whole) should worry about syllables because American speech is something again . . . bursting to pop.

Above all, a Haiku must be very simple and free of all poetic trickery and make a little picture and yet be as airy and graceful as a Vivaldi Pastorella.

Modern American Haiku was again more about the journey than the destination. Here are a couple of Kerouac’s:

One flower

On the cliffside

Nodding at the canyonYou’d be surprised

how little I knew

Even up to yesterdayAlone, in old

clothes, sipping wine

Beneath the moon

So why write haiku yourself? Writing haiku allows us to experience our lives as fresh moments, filled with wonder. They help us see beauty (which may be joyful, sad, truthful, wondrous…) in the details of our existence, whether nature, small actions, or surprises.

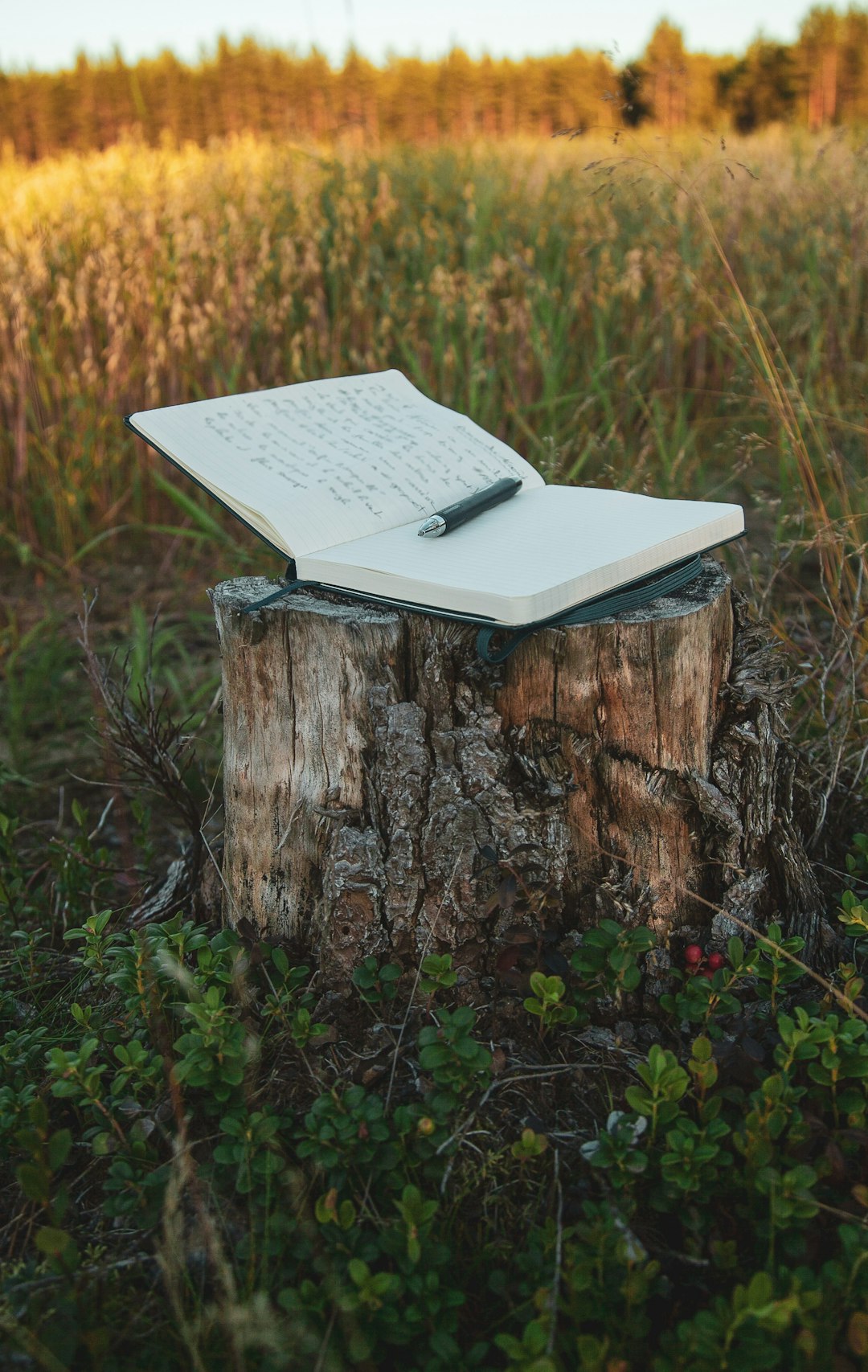

The experience can be a meditative one. The actual act of writing the haiku is a form of meditation. It can be something we compose in our heads while on a walk or sitting in a ski chairlift. It might be something you sit down to write to start your day. You could suddenly drift into haiku while writing in your journal.

The video above is an interesting reflection on writing daily haiku and one’s evolution through the process. Zezan Tam talks about the way writing haiku has given him gratitude for the many small things in his life, making him a happier person.

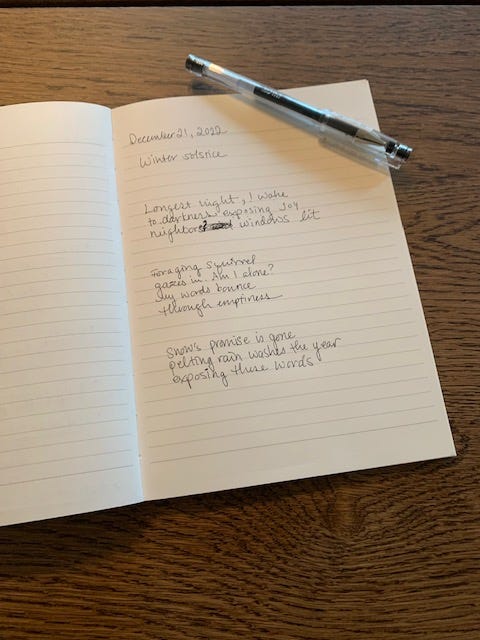

So if you try, please feel free to share one of yours in the comments. We would love to witness a slice of your world. Below, I’m pasting an eight minute go at it just after finishing this article on the Winter Solstice of 2022.

Here’s one fresh from the oven this morning.

one last glance skyward

barren trees lacking in grace

missing mistletoe

Lovely post, Kate. I have always found writing haiku (or attempting to) an escapist writing challenge. I wrote a few last winter after a particularly frosty walk in the woods; if I still have them I will share. I think the haiku is such a simple way to express the wonder of the natural world, and unlike composing formal poetry, it often feels less daunting to get 'wrong'.

Looking forward to your talk next week!