The Saturday Brunch: a figurative flat white or fizzy to start your weekend

One of the best classes I took at university was an art history course called Art of Zen with Professor Clifton “Cliff “Olds, who died in 2021 (linked obituary via Bowdoin College). I had taken a remarkable course in Italian Renaissance Art with Professor Olds and signed up mainly because he was teaching it but also because I had some interest in Japan due to my father’s work trips there while I was in grade school.

Professor Olds was a kind and warm man, small in nature but large in spirit. He asked us to call him “Cliff” when he later helped time us at track practice sessions and competitions, which was just one way he became in involved in the community. Probably because of this connection as well, I stayed in touch with Professor Olds from time to time after graduation and was deeply saddened when I heard of his passing. However, in addition to his family, he left a great legacy of work through Zen digital archives, articles and books, and - mainly - his many students and the way we now see the world a bit differently thanks to him.

The class - Art of Zen - focused on Japanese art but also attempted to define Zen philosophy or religion. Professor Olds was especially interested in other cultures and the connection between philosophies or religions and art, as he was in Italian Renaissance Art. Together we looked at beautiful paintings. He told us many stories and enlightened us to elements of the works we never would have seen on our own. But we were also asked to simply look and discover ourselves. How did the aesthetic speak to us? What is our own relationship with the universe, with nature? Who are our ‘masters’, our teachers of wisdom?

We often didn’t know the direction we were going in, but this was part of the magic. Professor Olds developed trust in his classroom; it was a safe place of discovery where knowledge is active and individuals are valued along with the subjects. The environment allowed for intellectual risk; there were more kōans than answers. I have taken this cue in my work as a teacher over the past couple decades, attempting to create the same kind of respect and trust among my students that he afforded us. I hesitate to use the word sensai, as Professor Olds was from Minnesota and not East Asia, but he was truly one of my most cherished teachers.

Zen & creativity

A lot of Zen is about doing and discovering; it is an active idea rather than something that can be studied in a stationary way. In the next few weeks, just for fun, I’ll guide you through the following practices:

Painting ensō

Writing haiku

Meditating (for the purpose of writing)

But first, let’s get a decent starting point about Zen Buddhism and a few artists from the tradition. Understanding these ideas, which includes ways to interpret the art, is a long journey and one that is always evolving. So try to embrace the really difficult questions it may bring up and dive into a practice of constant discovery.

Zen Buddhism

If you want to read a concise overview of Buddhism, the Asia Society has a good one here. Zen is a branch of Buddhism that places more emphasis on experience than the texts and theoretical concepts of traditional Buddhism. It is also more focused on meditation; some even say Zen is meditation; Zazen is the name for this practice. The Asia Society sums up Zen Buddhism in this paragraph:

Zen is the Japanese development of the school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China as Chan Buddhism. While Zen practitioners trace their beliefs to India, its emphasis on the possibility of sudden enlightenment and a close connection with nature derive from Chinese influences. Chan and Zen, which mean “meditation,” emphasize individual meditative practice to achieve self-realization and, thereby, enlightenment. Rather than rely on powerful deities, Zen stresses the importance of the role of a teacher, with whom a disciple has a heart-mind connection. This allows the teacher to offer the student helpful assistance in his spiritual development. Zen also values intuition instead of habitual, logical thinking and developed expressionistic and suggestive (rather than explicit and descriptive) painting styles and poetic forms as well as illogical conundrums (koan) to stimulate one' intuition.

So while Zen Buddhism may still be considered a religion by some, many consider it more of a philosophy or way of life. Of course, there is always crossover between religion and philosophy.

The BBC also has a nice, short overview that includes discussion of Indian origins as well as quotes about Zen, since it argues that definition is difficult to pin down. In fact, the BBC quotes both the notion that: “It is sometimes called a religion and sometimes called a philosophy. Choose whichever term you prefer; it simply doesn't matter” as well as “Zen is not a philosophy or a religion.”

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy goes into much richer detail about “Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy” and includes references to other important sources of information. I just want to go over a couple of key terms and features before we look at a few artists.

Kōan practice

Kōans are riddles without particular answers. They are posed by teachers or masters to disciples learning the way of Zen. Sometimes they are posed with a seemingly simple answer, but the riddle is in finding the way to the answer.

Here are two famous examples:

Without thinking of good or evil, show me your original face before your mother and father were born.

Question: Without speaking, without silence, how can you express the truth?

Response: I always remember springtime in southern China. The birds sing among innumerable kinds of fragrant flowers.

‘Just sitting’

This is form of meditation called Shikantaza, where one sits and does not do anything, including thinking. We will look at it more in three weeks when focusing on some meditation practices.

Three Step Process

We will also look at this more in three weeks time. The three steps of meditation are:

Adjustment of the body

Adjustment of the breathing

Adjustment of the mind

Monk artists & Zen painters

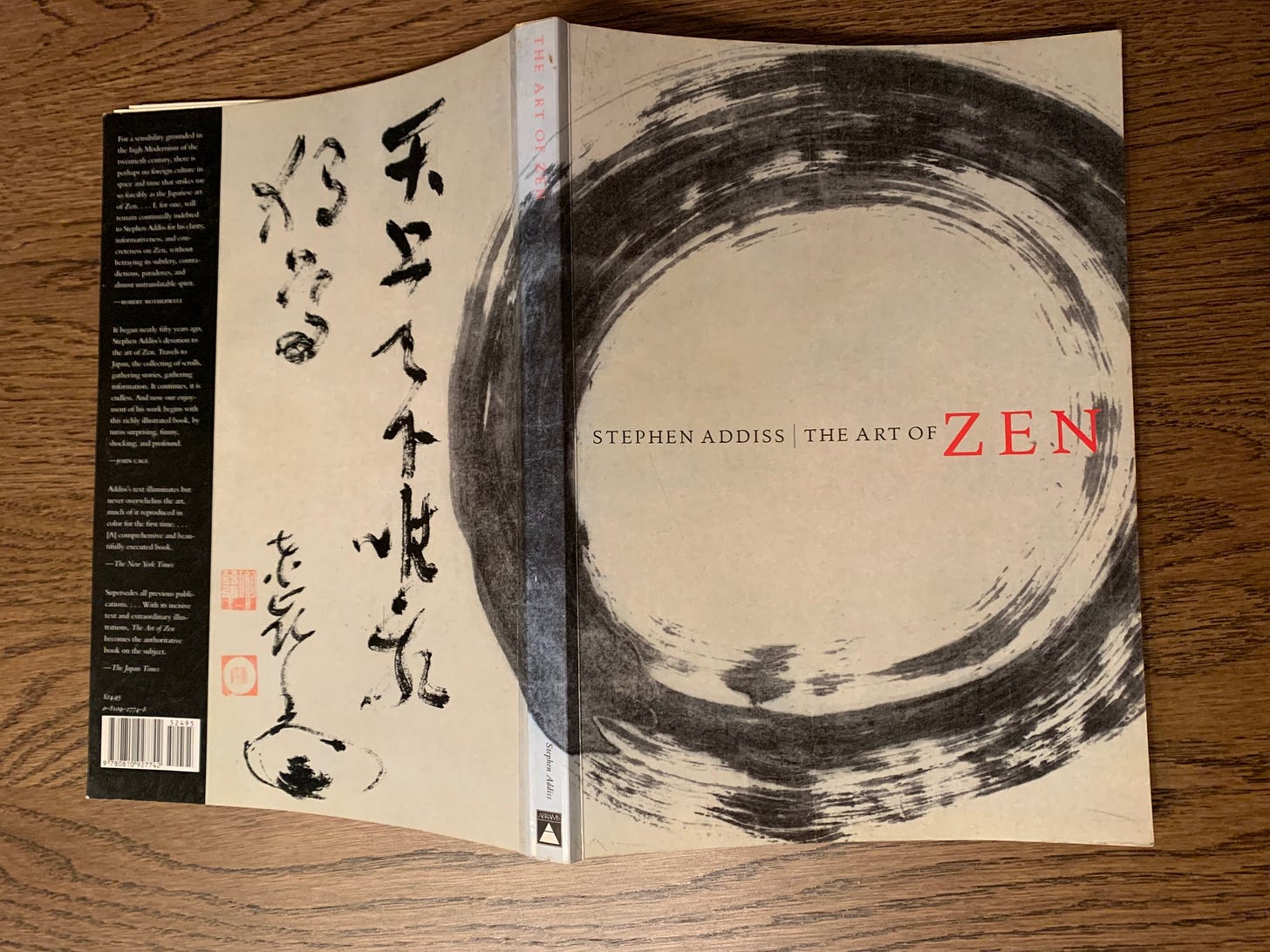

I highly recommend the book The Art of Zen, by Stephen Addis. It is one I used in my course with Professor Olds. He had met Addis, a long time scholar of Japanese art, and thought his books were by far the best method of explaining art of zen at least to English speakers. Addis even practiced the art himself and wrote Japanese calligraphy as well as translated works from Japanese to English. Sadly, he died this past year (2022). Here is an obituary from one of his publishers.

Addis starts the book by diving into the paradoxes of zen as well; as he puts it:

Zen is beyond words, but has occasioned countless books; Zen is individual, but requires a teacher; Zen is everyday and down-to-earth, yet is traditionally practiced in remote monasteries; Zen is profoundly serious, but full of humor; Zen demands being rather than representing, yet has inspired many different kinds of art. Zen teaches us not merely to hear, but to listen; not just to look, but to see; not only to think, but to experience; and above all not to cling to what we know, but to accept and rejoice in as much of the world as we may encounter. (p. 6)

Zenga

The book is “devoted to Zenga, the word the Japanese use to describe painting and calligraphy by Zen monks from 1600 to present” (p. 6). Zen art is traditionally created for the act of meditation, not for the purpose of sale or even display, although both of these practices regularly occur. The book also dives into anecdotes of the artists, often monks, and the way they went through their Zen journeys.

The book is filled with beautiful representations of a variety of Zenga that I can’t reproduce here. Here are a few useful videos from James Cahill at UC Berkeley. If you watch, you will hear him refer to Chan which is the Chinese word for Zen.

Kakejiku

One of the artists Addis talks about at length was called Tōrei Enji (1721-1792) who became interested in Zen Buddhism at the age of seven when he got sad about a classmate killing a louse. His life was filled with enlightening experiences, teaching engagements, art, and falling in love with a prostitute. There are rich descriptions on pp. 130-138, including telling people off for feeling to cold during his lecture and working with people of many different backgrounds.

Kakejiku are hanging scrolls, mainly with calligraphy but also with images at times. Tōrei’s “boldest example of calligraphy is his scroll bearing the names of three Shinto deities” (p. 133 and plate 70). Addis claims it is especially of interest because the writing looks “free and impetuous” but is actually done with great care and detail. The artist “evoked the primordial nature of Shinto beliefs by writing some characters in ways that suggest their original pictographic forms.” The changes he makes are subtle, with a particularly bold vertical line or another rounded form to conjure these images in the mind. He also used a gray ink (rather than black) so that the layers of writing and the movement of the brush could be seen more clearly.

Ensō

A scroll with a painted Ensō by Tōrei follows. The Ensō is the painting of a circle to represent many things at once. It is the action of painting the circle as much as the finished product itself that has meaning. We will look more at this in detail next week.

Modern Zen describes an Ensō in this way:

In the sixth century a text named the Shinhinmei refers to the way of Zen as a “circle of vast space, lacking nothing and holding nothing in excess”. At first glance the ancient ensō symbol appears to be nothing more than a miss-shaped circle but its symbolism refers to the beginning and end of all things, the circle of life and the connectedness of existence. It can symbolize emptiness or fullness, presence or absence. All things might be contained within, or, conversely, excluded by its boundaries. It can symbolize infinity, the “no-thing”, the perfect meditative state, and Satori or enlightenment. It can even symbolize the moon, which is itself a symbol of enlightenment—as in the Zen saying, “Do not mistake the finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself.”

Haiku

Many of the scrolls contain not only calligraphy but poetry, often in the form of Haiku. Most of us have created Haiku in school at some point. We probably remember the 5/7/5 syllable designation (although modern Haiku - and translations - don’t always follow this structure). We will have a try and a historical look in a couple weeks. If you can’t wait, have a look at the lengthier exploration by the Haiku Foundation.

Wabi - Sabi

Wabi and Sabi work together as Wabi-Sabi to help us understand the world through impermanence and imperfection. Omar Itani explains it well:

Wabi-sabi is a concept that motions us to constantly search for the beauty in imperfection and accept the more natural cycle of life. It reminds us that all things including us and life itself, are impermanent, incomplete, and imperfect. Perfection, then, is impossible and impermanence is the only way.

Taken individually, wabi and sabi are two separate concepts:

Wabi is about recognizing beauty in humble simplicity. It invites us to open our heart and detach from the vanity of materialism so we can experience spiritual richness instead.

Sabi is concerned with the passage of time, the way all things grow, age, and decay, and how it manifests itself beautifully in objects. It suggests that beauty is hidden beneath the surface of what we actually see, even in what we initially perceive as broken.

You can read more about it from Japan Objects or Sakura News (which includes a short activity).

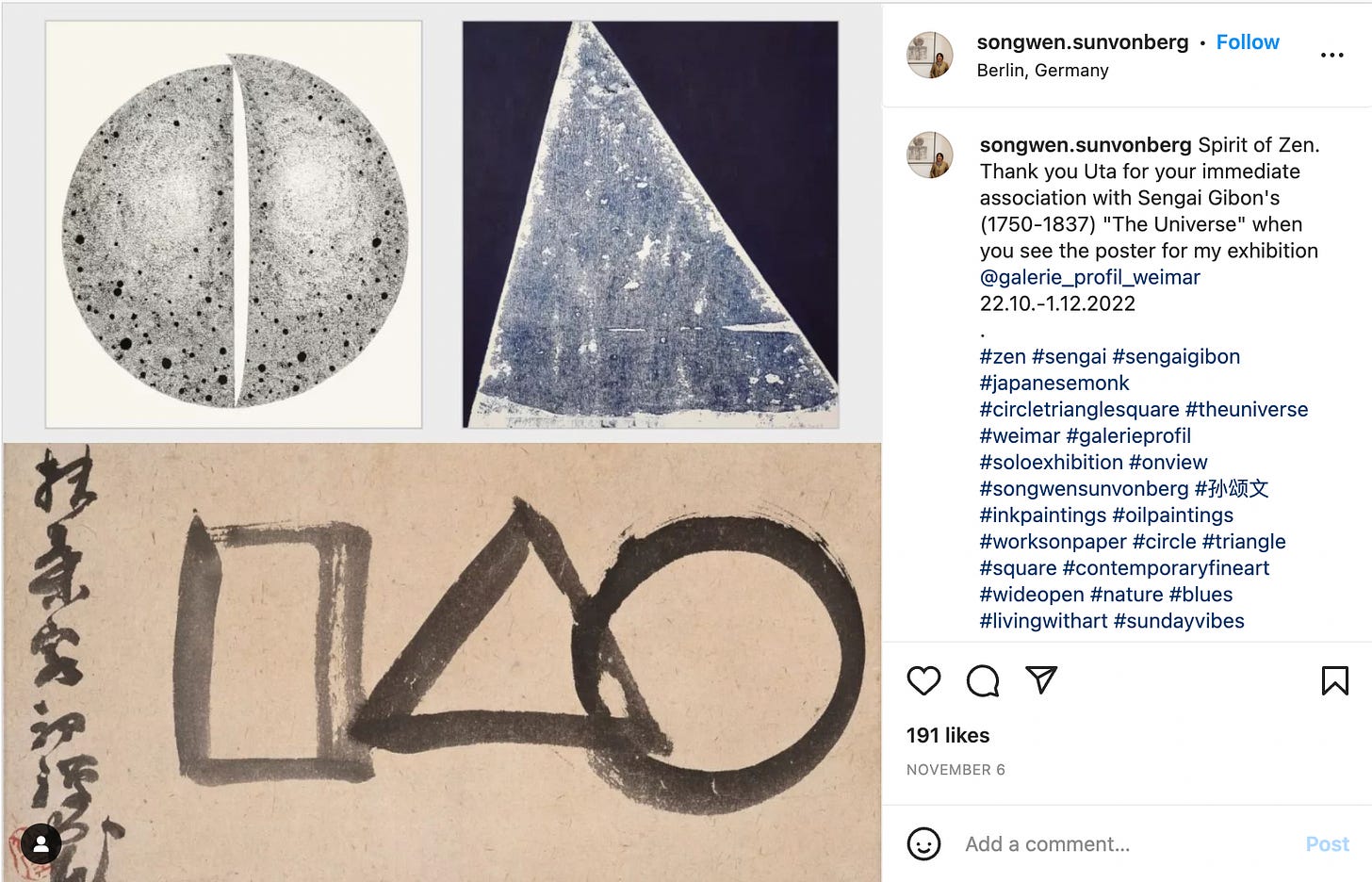

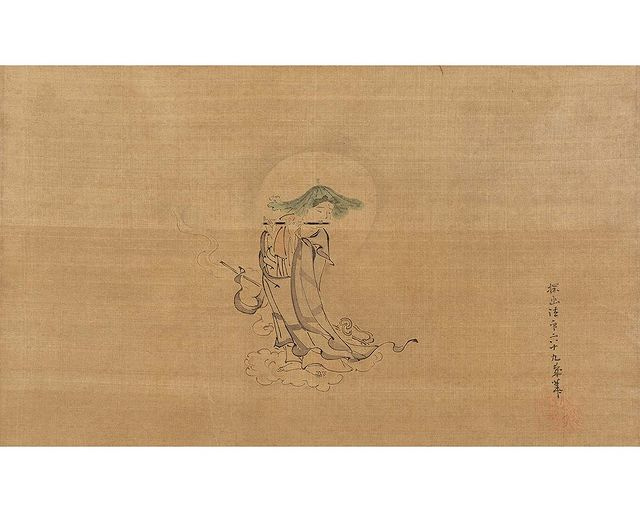

We can see this concept through Zenga in many ways. Sometimes it is the subject of ephemeral nature, for example, in a haiku or image. Sometimes the imperfection of an ensō’s circle will convey this message. If you look at the images below, perhaps consider the use of wabi-sabi in the creation of the compositions.

Above caption on Instagram:

Itō Jakuchū: Two Gibbons Reaching for the Moon

Hanging scroll; ink on paper

115 x 48 cm / 45.2 x 19 in.

Edo period, c. 1770

Kimbell Art Museum

Above caption on Instagram:

Ksitigarbha Playing the Flute Kano Tan'yū

9月18日~12月12日迄展示

September 18-December 12, 2021

ミネアポリス美術館 日本絵画の名品

Masterpieces from the Japanese painting collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

一幅、絹本墨画淡彩

21.3 × 35.9 cm

江戸時代、寛文10年(1670)

ミネアポリス美術館蔵

Hanging scroll; ink and light color on silk

8 3/8 × 14 1/8 in. (21.3 × 35.9 cm)

1670

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation

Here are a few great online resources to get some more background or have a glance at many Zen paintings and scrolls:

‘Zen Buddhism and Art in Japan’ (Asian Art Newspaper)

‘What is Zen Art?’ (Japan Object, Jess Kalled and Lucy Daymen)

‘Zen Buddhism and the Arts of Japan’ (McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture, Tennessee)

‘Zen Buddhism’ (The Met Museum)

Everyday Zen

Professor Olds included several interesting experiential elements of our seminar class. In addition to mimicking a Zen master who allowed us to solve ‘riddles’ or Koans included within the art we investigated, he taught us the tea ceremony that I’ll talk about in a couple more weeks and also had us write about a ‘Zen experience.’

What is a Zen experience? In fact, he couldn’t fully define it. It was for us to find and interpret. Anything meditative, anything allowing us to seek answers about the universe, anything allowing us to lose ourselves in the beauty of the world, any moments of enlightenment, any actions where intuition acted in our favor…these could be the experiences. The more important aspect was that we write about it in order to interpret its zenness.

My Zen experience ended up being a rollerskating session at a roller rink with my track and field teammates. This wasn’t something we normally did, but my coach was often planning alternative types of gatherings and team bonding, especially during our pre-season. It was late January in Maine and very cold. Any indoor activity, even for a winter lover like myself, was greatly welcome.

I felt freedom. I felt like a child — joyous without a care in the world, completely present in the moment filled with fun physical sensations (the skating itself and the roller rink music) and companionship of teammates. I wasn’t thinking about competitions, papers to write…or mortality.

You see, my roommate and close friend, who was also a teammate, had recently died in a car crash at the age of 19. The empty spaces of my apartment (that I still shared with another teammate) reminded me each day of her absence and caused me to focus too much on the past and the future: what we had together and what she had lost of her future as well as my own death to come. It was hard to ever feel present and peaceful. That is exactly what meditation wants us to do. I would posit that sometimes it’s easier to enter this space whilst moving the body, almost as a distraction for the mind until the mind is completely present and not distracted. Only then, I have found in my experiences, can I sit to truly meditate.

I wish I could find the essay now. I know I’ve got it somewhere. I also know that I’ve learned more about the experience and its impact on me as well as my understanding of Zen Buddhism since the time. It’s not because I took more art history courses or a philosophy course on the topic. Instead, it’s been through living these ideas and seeking art and writing about them that I have reflected on their value in my life.

Addis ends his book with a short epilogue and a last italicized line, suggesting his journey, and that of Zenga in general, is an ongoing one:

Zen art continues to be an awakening.

Thanks for reading and checking out this topic with me! Hope some of you will enjoy the creative journey the next few weeks. It will be accessible to anybody, even students or your kids.

"Though the flame be put out, the wick remains."

"Hi wa kiyurédomo tô-shin wa hiyédzu."

- I saved this in my notes in college. I hope it means what I remember. Killer zen moodpiece 😌

Fascinating introduction to the art of Zen. I remember reading about Wabi Sabi before and thinking it was a beautiful concept.

I am sorry to hear of your traumatic experience in college. Your description of experiencing Zen through roller skating reminded me of how much I used to love my roller skates and the freedom I felt on them.

I am the same as you regarding meditative practice: I need to move before I can even think about quieting the mind, which is why I enjoy a flowing yoga practice and walking outside in nature; both of these help me to reach the closest I come to a 'Zen' state of mind.

Very much looking forward to discovering more creativity in the coming weeks! : )