Solenoid

A novel by Mircea Cărtărescu (translated from the Romanian by Sean Cotter)

SOLENOID

noun — “a device, consisting of a wire wrapped in the shape of a cylinder, that acts like a magnet when electricity goes through it” (Cambridge)1

⬩

This post is a snippet of a journey, some pieces of the puzzle about what it means to be a writer and, therefore, what it means to live.

Maybe that sounds a bit too dramatic for the collaborative discussion of a single book. But I didn’t say it has the answer. No, instead this reading project has become something more than itself. Paradoxically, perhaps, my collaborator and I have decided to be reductionary in our approach. Once I attempt to provide some context to the project and the book, with the assumption that most readers haven’t read it, we bring you our condensed responses to six selected passages from the 672-page tome. The hope is that the gaps provide as much potential for realizations as our prose.

At its core, Solenoid is a novel about a school teacher and former-aspiring author living in communist Bucharest. However, the story moves through memory and life experiences to grasp existential questions while seeking acceptance. Mircea Cărtărescu’s poetic prose takes us to deeply internal moments of pain or love alongside greater questions of human solidarity and the supernatural, at least as it lives in our minds.

, the author of , recommended Solenoid to me back in October 2023 in the comments of an essay/podcast about “The Intrinsic Link between Memory and Novels,” which would certainly discuss this novel if I were working on it at this time. I happened to be in London and attempted to find the book at several bookshops where I was greeted with perplexed brows from shopkeepers and the suggestion that they could order it for me. I wanted to have a look, to feel it in my hands and check out the prose myself, but the book’s continuing absence intrigued me more. With further discussion elsewhere from Nathan in regards to this book, though he was still in medias res of the experience, I was propelled to order it online.I picked up the book immediately upon receipt despite a large pile already on my desk. After an opening sequence about head lice, I was hooked. Unsurprisingly, the subject of lice was not what inspired my appetite for more but the manner of the immersiveness and courageousness of the writing. After a couple of slow months when I was multitasking with research related to podcast recordings, and a long trip to my parents’ in Boston where the heavy pages just wouldn’t fit into the Christmas-present-filled suitcases, I dove all the way in during a winter of introspection. Finally after several stops and starts due to other trips when the book just wouldn’t fit, I finished. I was left with a feeling of awe and the need to talk about the experience into which Cărtărescu had taken me.

Nathan wrote a short essay about his experience with the encounter of Cărtărescu’s writing in “Wire-bound words, or, a brief discussion of magnets” where he alluded to the possibility of today’s post. He writes:

This book has changed my life.

Most of all, though, this book has changed the way I think about writing. Some fleck of its insanity has become lodged in my brain. If there has ever been a book that pushes me, convinces me, that what I really, really want to do with my life is to write, then it is this book.

I recommend reading his entire early response (and traveling with him on his experimental, philosophical, and often personal journey with fiction).

Regarding this life-changing feeling, I had the impression that Cărtărescu had articulated ideas I felt deep within that were previously indescribable. He gave language to the abstract musings or these fleeting things that you feel you might grasp within a dream or during a run (in my case)…instead, they retreat to the recesses of the mind, not in the head but in small places like my left femur or right index finger or ninth vertebrae in my thoracic spine. Albeit, the great Romanian author wrote these thoughts in still cryptic forms, symbolic segments of puzzles that constantly shift, moving faster the closer you are to placing them together.

This idea of the embodiment of the vastness of these ideas is also reflected in Solenoid. Cărtărescu’s work is as much of the body as it is of the great beyond. It conjures Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony” in this way — at once an individual caught up in a macabre game of power and (in)justice as well as a remark on a political ideology (for Kafka, colonialism; for Cărtărescu, communism).

This was an implicit subject of a discussion that Cărtărescu had with his translator, Sean Cotter (whom the author holds in great esteem and as part of the creative process), and which is available in a video via Bass School at UT Dallas (also embedded at the end of this article). After reading a passage in Romanian and English about tattoos that cover the body inside and out, the authors discuss Kafka and others who write authentically without the need to write for a reader. Paradoxically, the effect can become something that speaks more vividly and deeply to a reader. This authenticity is something Cărtărescu attempts to achieve in his writing. One way he does this is through a process of writing his manuscript without editing (according to him)2.

The pair also created something to aid us with the puzzles of the text, or perhaps to radiate the labyrinth into a multidimensional, infinite amplification. The Solenoid Reader is available for free from the publisher as a download. I’ve only scratched the surface, but it has the effect of Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project that bombards us with quotations, musings, anecdotes, and poetry. Of course, Benjamin’s work was published posthumously, which is part of the reason it is presented in puzzle-form. Perhaps this creates a more authentic artwork, according to the discussion from Cotter and Cărtărescu. I also think of books like Moby Dick, To Walk Alone in the Crowd, Orlando, and Istanbul: Memories and the City that all seem to eschew definition or linear narration.

At the link, you can also read the translator’s description of this accompanying text, which concludes: “Solenoid readers follow these raveling threads through this group of texts toward other texts, searching for further coincidences and still further constellations of meaning, reading in the shelter of these frightening stars.” I think his words here mostly refer to the original novel as well. It is a “Vertical Book,” in the words of the author, one that moves us up into some kind of abyss whilst simultaneously grounding us in the everyday world of human “solidarity” and love. Although some may see his style and length as grandiose and even imperious, I took away this message more than anything.

And, if you happen to listen to the video, you will hear a story of an accidental meeting with a reader in Guadalajara who was “saved” by this book. Cărtărescu seems to put more value on the shared tears of humanity between author-and-reader than on his awards and accolades. As a teacher-writer myself, I think that human connection of the teacher he was in the eighties is still a strong part of who he is as an author. Because great teaching, after all, starts with connection and giving voice and epistemological power to one’s students.

⬩

Without further ado, we bring you the chosen passages and our responses…

Passages from Solenoid, selected and discussed by Nathan and Kate —

1

The Fall, the first and only map of my mind, fell the evening of October 24, 1977, at the Workshop of the Moon, which met at that time in the basement of the Department of Letters. I have never recovered from the trauma. I remember everything with the clarity of a magic lantern just as a torture victim remembers how his fingernails and teeth were pulled out, when, many years later, he wakes up screaming and drenched in sweat. It was a catastrophe, but not in the sense of a building collapsing or a car accident, in the sense of a coin flipped toward the ceiling and falling on the wrong side. (p. 32)

Nathan: We circle back to the Workshop of the Moon (amazing name, by the way) later in the novel, but this is the moment when we glean what this story is truly about. This fork in time, this reflection by Mircea seemingly about his own life and how he has inhabited the other side of that coin but that what you hold is the wrong side, the way it all could have fallen.

Kate: It’s so fascinating to go back to this paragraph after reading the book. I love when a novel responds to its opening. Truly, this is a catalyst for some kind of plot (though abstract), but at the same time, it holds the seeds of certain more developed themes — trauma, writing ‘success’ and visibility, dreams/nightmares, fate… I read it completely differently now. In fact, I remember being confused about the logistics of this aspect of the plot until watching the interview (below). Somehow it felt superfluous at the time of reading. However, now I see this mundane contest and failure as much more symbolic of other ideas in the novel.

2

As long as I can remember, I have had a strong feeling of predestination. The very act of opening my eyes in the world made me feel like I was chosen – because they weren’t a spider’s eyes, they weren’t the thousands of hexagons of a fly’s eyes, they weren’t the eyes on the tips of a snail’s horns; because I didn’t come into the world as a bacterium or myriapod. The enormous ganglion of my brain, I felt, predestined me to an obsessive search for a way out. I understood I must use my brain like an eye, open and observant under the skull’s transparent shell, able to see with another kind of sight and to detect fissures and signs, hidden artifacts and obscure connections in this test of intelligence, patience, love, and faith that is this world. As long as I can remember, I have done nothing but search for breaches in the apparently flat, logical, fissureless surface of the model within my skull. (p. 76)

Nathan: The quote is from near the start of the book where several key and repeating themes are established. Predestination and fate, the introspection of self-awareness and consciousness. We are aware because we are aware. Such awareness can extend within and without. As a scientist, often I have grappled with a sense of fate, for good or for bad, that has positioned itself across the path of my life. I selected this passage not only because of the themes but because it is a perfect example of Mircea’s prose. Phrases such as “the enormous ganglion of my brain” and “fissureless surface of the model within my skull” are what I am here for. It is what pulled me in from the start. If you like this then there is a high chance you will enjoy the book.

Kate: This is a great quote. I’m so happy you chose it and think you hit the root of it clearly in your response. I’m interested, too, in the corporal elements not only here but throughout the story. It’s so visceral, occasionally disgusting and other times magical in consideration of the mind-body connection (and beyond). I don’t know to what extent your research works with biological aspects of the human body, but I can see how you might respond from this scientific perspective. All the time he talks about his brain (etc.), there is also a kind of surpassing of it, where the skull becomes invisible and the connections of the brain are almost tangible and visible. I love this way of thinking about the protagonist’s consciousness.

3

No novel ever gave us a path; all of them, absolutely all of them sink back into the useless void of literature. The world is full of the millions of novels that elide the only sense that writing ever had: to understand yourself to the very end, up to the only chamber in the mind’s labyrinth you are not permitted to enter. (p. 209)

Kate: These passages about writing were so difficult to read because they speak of this horrific fear about wasting time writing (or reading). Cărtărescu comes back to this ambiguity about the writing practice continually in the book, trying to perhaps make sense of its purpose. He seems to question writing as a compulsive act at times, taking away from his real life. He also constantly plays with the dialogue of literature, implicitly or explicitly. On the one hand, he elevates it to a kind of sublime space. On the other, it is something just as ephemeral as a butterfly and, perhaps, unable to explain anything in clarity. However, there is this pervasive idea of the personal, both that writing is for the author and that specific individuals can connect with the shared consciousness of that author. The labyrinth, it seems to me, refers to Borges. Although it is also a more general puzzle that includes all literature. Also, the “useless” comment makes me think of the foreword to The Picture of Dorian Gray: “All art is quite useless,” which shows its elevation beyond something of everyday use.

At times, Cărtărescu really made me question the purpose of the time I spend writing. So immersive was the experience that I felt like throwing it away one minute, but fighting within myself for those reasons the next, even if they may feel tiny and invisible. I think this is what the protagonist concludes as well, but it’s unclear because the conclusion is also about living with those on Earth instead of floating off into this metaphysical world, untethered.

Nathan: It’s already possible to see some patterns from the book, even from just these so far. The interiority of the writer and the reader. I have never felt introspection like I have when reading this book. I found the act of reading Solenoid – and continue to find it, even now, several months later when coming back to Mircea’s words – arresting. That is the only word I can place here. Do we expect to find a path in literature? I don’t know if I’ve ever approached reading with a vision or desire to understand myself. Perhaps that is why I started writing.

4

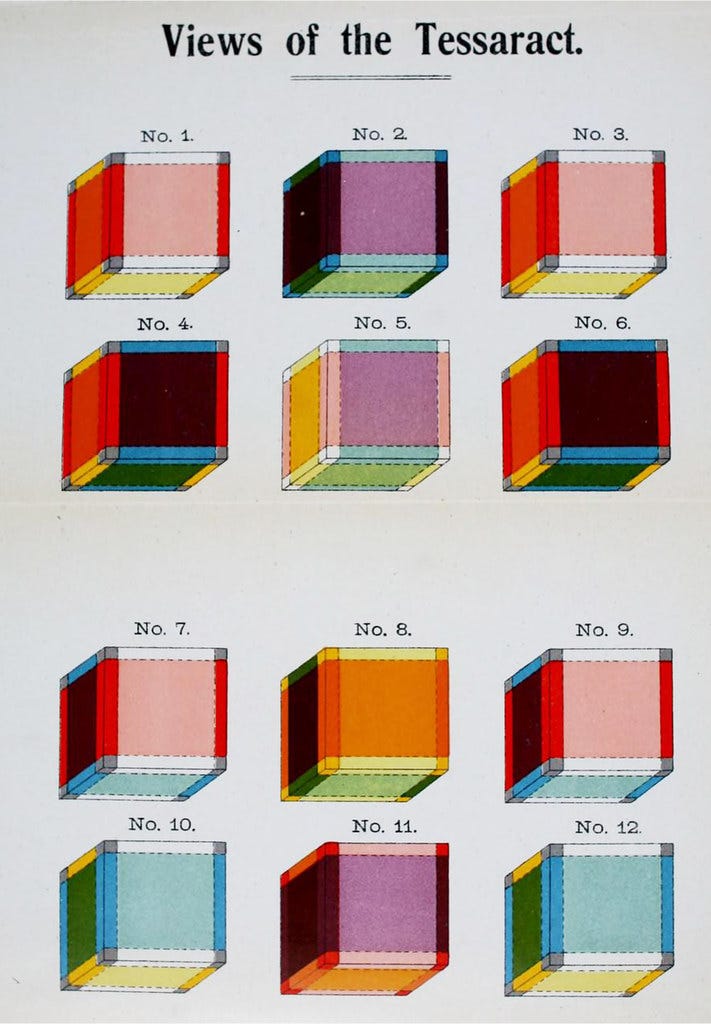

Hinton used his mind in the same way to understand the unintelligible, to record, like the poet whose eyes he had, the inexpressible. Through analogy and telescoping, he spent his life in an attempt to surpass the intuitive forms of three-dimensional space, the only forms where our mind feels at home, because it was shaped by them and has their form; to compel a three-dimensional brain, focuses on the volumes of our world, to let its hemispheres diverge; to contemplate, aimlessly and dreamily, until the familiar forms melted and, suddenly, like an epiphany, opened a portal to the fantastic dimension immediately above our own, a dimension until then accessible only to saints and to the enlightened. Breaking through the prison of these three dimensions through the use of mathematical reasoning equals, in fact (or doubles, as proof that in the end, all the paths of knowledge converge on an incandescent point, mystical-poetical-logical-mathematical), ecstasy, divine infection, the blinding state of satori. (p. 352)

Kate: I love so much about this passage and the pages that come before it about the tesseract (which immediately conjured A Wrinkle in Time for me). The interdisciplinary nature of Cărtărescu’s thinking moves beyond boundaries we often categorize knowledge within. Why not consider “satori,” the Japanese Buddhist word for awakening, as something achieved through mathematics combined with poetry? It feels seamless within the context of this mind we are privy to. It also feels like a wonderful way to experience the world as a mathematician or physicist at this level of philosophical and abstract thinking, although perhaps overwhelming as well. It’s something filmmakers like Christopher Nolan (Oppenheimer) and Ron Howard (A Beautiful Mind) attempt to capture through other means of depicting consciousness3. Partly, I think this passage demonstrates the ability of humans to think beyond what is already known or taught. In some way, we each have this capability.

I wonder, Nathan, if we both selected the passage because we are avid Murakami readers? I felt so much of his parallel worlds and Zen movements within the text, but especially here. Or rather, there is a kind of summary of those points that are implicit throughout the rest of the book.

Nathan: I find it both amusing and unsurprising that we selected the same passage. It was inevitable, I think. This was one of the many moments where Mircea would take a subject and run with it for several pages, as well as circling back later in the book. The exploration of the tesseract was eye opening. And you’re right, even though Murakami is a completely different author, there are overlapping themes. “Zen movements within the text.” How right you are. It is impossible for me to articulate the sense of feeling I get when reading certain of Murakami’s books, but “Zen movements within the text” is an apt description. These two authors are different in style and prose, but the conjuration of feelings they invoke are so similar.

5

I picked up a sign that read, “Help!” left behind by someone in the departed crowd. The word might have been scrawled onto the cardboard with a bloody finger, by one inscribing the secret name of each of us and of our species. “We live for a nanosecond on a speck of dust lost in the cosmos,” I said to myself, and I returned to the dentist’s office, where the four chairs glowed, pure and fulfilled, in the light of their own panels of bulbs. (p. 568)

Kate: So just before this paragraph are seven pages of “help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help! help!” repeated endlessly in a “song of our fearful agony” delivered by a “chorus.” It feels like a Greek chorus, somewhat outside of the text, but responding emotionally to its content. I must admit that I came across these pages when flipping through the book, and it inspired me to read faster to find out what was going on. It felt like a cry we all feel at times. Sometimes, I let it out quietly if I am home alone, as if acknowledging we need help allows us to get it, even from ourselves. As writers, perhaps we cry out implicitly throughout the writing process for some kind of connection or shared pain. What do you think?

Rather than bring us into a deep dive of despair, the passage seems to bring us together. A shared humanity. Common existential questions about our world and our isolation. Now, in this paragraph, he’s come back down to Earth, in a dentist’s chair of all places. Several passages deal with bodily pain, including a frightening trip to the hospital as a child, made more frightening through the denial of his memory by his mother. The sharpness of mortality -- a mere “nanosecond” of life -- somehow coexists with this mind that appears to live in an infinite type of world, connected to all even with that searing isolation.

Nathan: What I love about this quote is how wild it must be for anyone who hasn’t read the book. So much within a few words that have been sliced out of the page. Here we find another recurrent theme, that of existentialism and our place in the vast timescale of the universe. Even a nanosecond is too long, I suspect. And you’re right, Kate, the passage begins a process of re-grounding the reader, asking us to accept and be at peace with the existential mystery of life. I have said before about the feeling the book gave me as I read, and I think this is part of that. It was meditative at times and that, in part, why was it was a joy to read it at a slow pace.

6

The essential ambiguity of my writing. Its irreducible insanity. I was in a world that cannot be described, and definitely not understood, through any other kind of writing, insofar as it can be truly comprehended. Revealing is one thing, and the painful process of reverse engineering, which is true understanding, quite another. You have before your eyes an artifact of another world, with other dawns and other gods, an enigmatic Antikythera mechanism4 that shines, floating in the air, in all the details of its metal brackets covered with symbols and gears. It was difficult to retrieve it from the bottom of the sea, from all its oyster beds and undulating algae, to meticulously clean off the crust of petrified sand and rust, to grease it with glittering oil, to set every gear in place so all the teeth fit together, and this is what my manuscript has done, up to this point: it has revealed, brought to light, unveiled what was hidden behind veils, it has decrypted what was locked in the crypt, it has deciphered the cipher of the box where it lay, without even a dash of the unknown object's shadow and melancholy dripping into our world. (p. 574)

Nathan: So here we are, near the end of the book. This is a long passage dealing with the process of the narrator’s writing of a manuscript. I selected it because it is, quite surely, self-referential to Mircea’s own process and his feelings of what it is to write. The manuscript – the same one you hold when reading Solenoid – is an artifact dredged from the waters of the author’s own mind, complete with its inherent mystery, a labyrinth that can only be explored once it has been committed to the page and the waters drained from its many chambers. We, the reader, find ourselves exploring the words as much as the author does. Such exploration requires effort. At least, that is my interpretation. Having listened to Mircea’s interview (linked below), the fact that he does little to no editing, letting instead the words merely arrive on the page unaltered, seems to fit.

Kate: I agree with your interpretation about this metafictional passage, Nathan, especially after listening to the interview as well. I guess even if it’s not an accurate representation of the author and his practice, it allows us to come to similar conclusions through the writer-narrator (à la Borges, Murakami, Kundera, or Auster…). I like this idea of the ‘secret’ being ‘revealed.’ Although the world he describes is some sort of completely abstract and incredibly earthly duality, as if they have a reciprocal relationship with each other rather than merely coexisting, the message is rather simple and clear. That is, he asks us to live in the real world and try to seek that pearl in the “oyster bed” despite the world’s harshness and our own traumas.

I’ll end by thanking you again for introducing me to this incredible text, Nathan.

★ READERS — Please share your thoughts about these passages, even if you haven’t read the book. The passages are numbered for easy reference. Thanks for joining us today in the culmination of several months of reading, pondering, and discussion. It has truly been a rewarding project! ★

Read about “Solenoid Applications in the Modern World” on Professional Dude.

Discussed in the video as well as this interview with Music & Literature, for example.

Seeing beyond scenes: Oppenheimer and A Beautiful Mind

Ancient Greek model of the solar system. See Scientific American.

The only disappointing thing about seeing this post arrive just now is that I'd already read it yesterday 😉

Wonderful analysis. This book should be required reading for, well, everyone :D

What an absolute banquet this piece is. Thank you both for a brilliant discussion of what sounds like a brilliant book. It sounds as if Kate's persistence in tracking down a copy was entirely justified. Too much to say so I'll just highlight this:

“We live for a nanosecond on a speck of dust lost in the cosmos,” I said to myself, and I returned to the dentist’s office, where the four chairs glowed, pure and fulfilled, in the light of their own panels of bulbs. (p. 568)"

I love the fact that the four chairs have more confidence in the fact of their existence than the writer!

When writers mine their own despair they are connecting with their readers, all of whom have probably experienced it. By reading and writing about it we feel less alone, and existential despair, which can be overwhelming, is relegated to its context as just one of a huge range of emotions that every human must experience.

Thank you both. Brilliant.