Read Less but Read Better

The best advice I got as a PhD student is the unexpected advice I give my literature students

This is an article I published earlier in the year with Better Humans. Maybe it can help to frame discussion of how we select our reading when there is so much choice out there. Part of the aim of this publication is to learn from careful curation about a topic that also allows for potential near-infinite related sources. But how do we do that without feeling overwhelmed?

The last piece of advice you might expect to receive from an English teacher is to read less. No, not because you’re not capable of reading more nor because there is some sort of hierarchy of worthy canonical literature. I am here to ask you to trim down your reading goals, and, paradoxically, by letting go of the expectation, you just might find you start reading a little more rather than putting off all those book projects on your shelf or saving articles for…later1.

By reading less but reading better, no matter what you choose to read, you can become a better thinker and knowledgeable person. More importantly, you can find pleasure in reading. You can also let go of an imagined expectation to access all that is available to you to consume in the form of the written word.

When we’re overwhelmed, we often shut down and freeze. This can easily happen with reading; it doesn’t mean you are weak or lazy. Over 2 million books are published each year. Even if you had a goal to read just one percent of these books, you would read 20,000 of them. This doesn’t include all the books from the past that you still haven’t read nor does it include any of the millions of articles available at your fingertips that you should be reading.

And yet, we — as voting citizens or parents or teachers or writers or friends — we are supposed to be well read. We are supposed to understand from different perspectives, to read the latest but also know the classics, to know about pop culture, educational trends, Kantian philosophy, the best foods to eat for longevity, and the history of the world including all the dynasties of China and which 22 countries have not been colonised by the British. How can we ever make it out of the word-weeds?

Over a decade ago when I was starting my PhD, I was lucky to sit down for a chat about my research with Hong Kong scholar Akbar Abbas, currently professor of comparative literature at University of California, Irvine. I thought we would talk about filmmakers or poets, perhaps investigate some ideas about critical spatial theory. We didn’t talk about my research at all. Instead, we talked about reading.

I told him it could be overwhelming. There was so much out there. Although I embraced not knowing as an English teacher and learning alongside my students, the thought of being exposed of the gaps in my knowledge in an academic conference were horrifying. Every search on the University of Hong Kong database for one of my keywords came up with hundreds or even thousands of hits. Even narrowing the search down for several indicators produced more than I could read during my five-year degree…or even during my lifetime. On top of that, I was tackling tomes like Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project and Gilles Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition — in French. This was in addition to the literary texts that would form the basis of my project. All of it was starting to form a mush in my head that made me question if I was even capable of completing a doctoral program. Did I really have anything original to say?

The kind scholar cut into my tear-threatening thoughts: “Read less.”

“Excuse me?” It went against everything I thought about being an expert about something.

“Read less. But, read better!”

Even before I fully understood what Dr. Abbas was saying, I felt a huge weight lifted. He went on to explain that sure, you have to vet what’s out there. But you can quickly discard or at least set aside most of it and focus on what looks useful. Some texts you might have to skim-read or search for keywords. “But mostly, you need to read carefully. Read what’s good and what speaks to you in a fully immersive state. Read it a second time, maybe a third! Don’t worry about knowing everything; you never will anyway.” His warm laugh vibrated life through all the bland furniture in the tiny meeting room.

“And mostly,” he said, “it comes down to trusting yourself and your own ideas.”

The same is true in real life (for those who see academia as an imaginary world). We all have a set amount of time. Some prefer to spend more of it reading than others, and that’s fine. None of us, however, can expect to read all the books and articles that look interesting to us in a lifetime. We have to be selective and not think about all the things we haven’t read, because there will be exponentially more and more out there, creating a black hole in our minds that will eventually suck up the good stuff we are trying to consume.

What’s the real problem?

Do we feel overwhelmed by reading because there’s too much available? Or is it because (post)modern time feels rushed or even slightly schizophrenic2?

In 2018, The New Yorker investigated ‘Why We Don’t Read, Revisited’ to try to make sense of falling numbers of minutes that Americans spend reading. In fact, they showed, the Americans who do read were reading more while fewer are reading at all. Perhaps the reason is a feeling of being overwhelmed. Many people don’t know where to start.

In the recent alternative time management book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkeman discusses this “existential overwhelm” as something that can be combatted through paying attention to details — mindfulness (p. 45). (I say alternative because Burkeman has spent a lot of his life researching and reporting on traditional time management strategies; instead here, he draws on a new mindset, research, and Buddhism to get to the heart of the matter.) In reading terms, this means to pay attention to words, and possibly the way they make you feel or impact your thinking. Or, it may be to simply relish in their aesthetic beauty.

Some of the best moments in my classroom have not been the students’ huge lightbulb moments about an ethical idea or the deeper understanding of a subversive plot line. These are the goals I expect. Instead, the classroom has forced all of us to slow down with a page, a paragraph, or even a single sentence to admire its construction and sound, to delight in the imagery or emotion it has created in our minds.

There may be no more vivid demonstration of this ratcheting sense of discomfort, of wanting to hasten the speed of reality, than what’s happened to the experience of reading. Over the last decade or so, more and more people have begun to report an overpowering feeling, whenever they pick up a book, that gets labeled “restlessness” or “distraction” — but which is actually best understood as a form of impatience, a revulsion at the fact that the act of reading takes longer than they’d like. — Oliver Burkeman in Four Thousand Weeks (p. 158–9)

As I have recently turned to write full time3, I have to recreate these experiences on my own. But with the pulls of other demands — the writing, my son, doing the groceries — it always seems there is something more important than looking at a one-page poem for an hour or two. The problem, according to Burkeman, is that we are “too impatient to read” rather than lacking time to read — and we may be impatient because we feel there are too many things we should be reading (p. 159). Whether you give yourself 20 minutes or two hours, you need to be armed with a method of selecting your reading material or you might spend the full time merely perusing.

Technology could, of course, be one issue. While it might help us to read faster, it amplifies the ‘existential overwhelm.’ Does the time we spend scrolling and texting take away from immersive reading? Probably. Or, what about interruptions? You might read an article or book online, open a hyperlink, open a second hyperlink in the next text, and eventually forget where you started. There’s reward in this journey, too. We might end up in unexpected and exciting places.

There are infinite possibilities of reading material at our fingertips at low to no cost, from online articles to e-books to mixed-media publications. Perhaps with so many options, though, we shut down. How can we structure these infinite possibilities into something meaningful and manageable?

Structuring your reading

I’ve taught literature to high school and university students for over twenty years and most of them tell me they read the news before revealing, after my probing, that they just receive notifications or skim headlines. Headlines now dangerously tell us so much information that we are often not tempted to read on. And instead of a paper form that is contained within our hands, we quickly scroll through different information, knowing most of it will always be there should we want to come back to it at a later, more convenient, and non-existent time in the future.

One method to make sense of our reading online is through curation, whether it is your own or that of others. I like the Quartz daily brief, because it includes links to articles from all over the world, often showing different angles of the top news of the day. Another I loved was The New York Times’ What We’re Reading (although it stopped in 2018), which highlighted interesting features from other publications. Some newsletter writers also have pinned lists of articles they are reading. If you find curated lists like this that work for you, it can be a nice once a week or once a month focus.

Of course, you can curate your own lists as well. Sometimes the problem is there are so many. With all the ‘save for later’ buttons, you might end up with hidden to do lists in every app on your phone. Unless you only read on a couple of platforms, which could be another solution, this also becomes a source of shutdown. Making a centralised list is useful, whether on Diigo and Toby for laptop readers or Flipboard and Scoop.it on a mobile…or a simple Google doc with links. The key is having one place to look that keeps you organized and saves time when you do have a few moments to read.

You might make a small goal. With students, I ask them to commit to three articles a week. It doesn’t sound like much, but many of us may read hundreds of headlines and first paragraphs without seeing through a longer article. Your goal might be a time rather than amount. You can set a distraction free timer on your phone — it’s amazing how long thirty minutes without pings can feel.

You may also have huge lists of books you want to read, whether on paper or in your head. Goodreads can be a useful tool for keeping track of what you want to read and what’s on your bookshelf. You can also set a year long goal, and though it seems to go against the ‘read less’ philosophy, sometimes having a tidy list can help you to see the reading you have achieved and allow you to consciously decide on priorities. I use this platform and cut my goal in half this year to facilitate a few monster books I wanted to spend time tackling at a comfortable pace, but more on pace below. If you don’t want to give your data over to Amazon, just make your lists in a little notebook or pile the books on a single shelf that you know are waiting for you to grab.

For students who struggle with the literature that we read in book form, I ask them to do a quick read of the whole text and offer them certain page numbers to focus on more carefully, to read a second or third time. It doesn’t mean the rest isn’t important, but through this method, the student gets a lot more out of the book and has more tools and confidence to continue reading other books on their own. Sometimes I use this method myself if it’s a book I’m curious but don’t want to use xyz hours of my lifetime to sit down with. Or, it can be a good re-reading strategy.

The key is that we can make intentional reading lists to facilitate more present and goal-oriented reading. Within this general approach, the choices you make depend on your preferences and situation. While I can give you some ideas below, you will need to experiment and reflect to figure out what works for you.

How you do it

As you are well aware, books can be bought or borrowed, both in paper electronic forms. Figure out how you read best — what you enjoy and what is most convenient for you and your lifestyle. I loved my Kindle when I was traveling for large chunks of time and wanted to bring several books along with me. It was also useful living in Hong Kong where English books were more limited and take a long time to ship from the UK. I soon realised, however, that the ease did not outweigh the joy of turning paper pages in my hand. I also had a harder time being fully immersed and rarely turn to the Kindle these days.

For short pieces of writing, the variety is much greater and cheaper online. However, I still enjoy sitting down with the FT Weekend when I know I’ll have a couple hours on the weekend or purchase a glossy magazine before boarding a plane. I enjoy being able to switch off and to be unknowingly bombarded with different types of articles rather than selectively clicking or searching for keywords. There are always unexpected treasures.

When you do it

If you want to read on a daily or weekly basis, you can figure out what works best in your schedule. This will depend on when you work, if you have children or other dependents, and when you enjoy reading.

When I had a 40 minute commute, the bus or train was my reading time. However, I knew it only worked in the morning. By the afternoon, my brain was fried, so on the return I listened to music or talked with a friend instead. Many people change their reading to audio so that they can drive or walk while listening. Again, don’t just do it because it saves time; do it if it really works. I don’t get much pleasure or knowledge from audio-reading, but my husband can even listen to books while he works out.

My commute reading was later challenged with the fact that my baby would be traveling along until day care drop off. And currently, I have no commute. Hoorah! But then, when can I structure time to read?

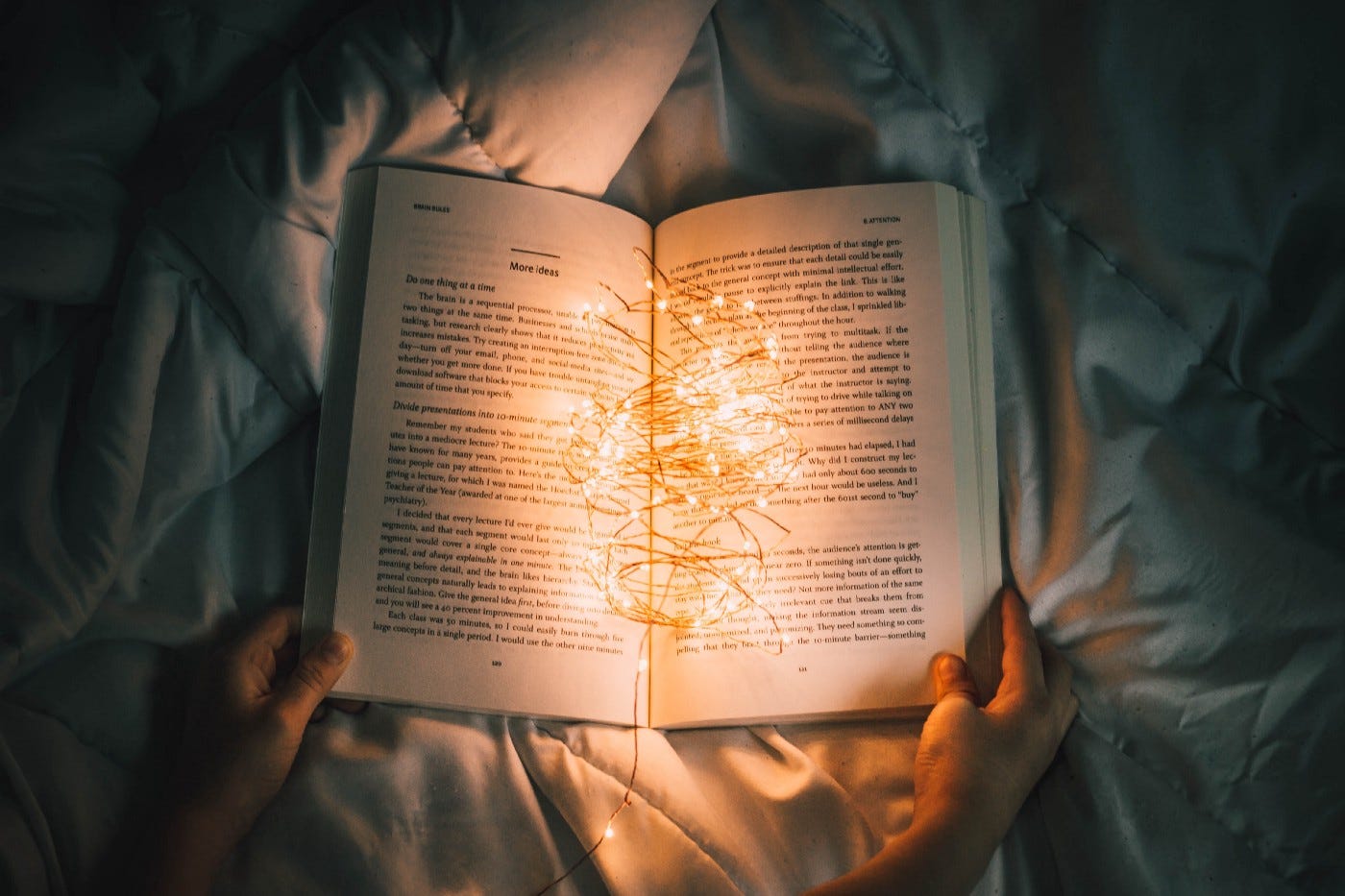

Some people do it as soon as they wake up. Some do it just before bed. Some the second half of a lunch hour. Some on a coffee break.

I don’t keep a daily goal anymore. Instead, when my spouse is the one putting our son to bed (which can take up to an hour), I sit down with a book. I also choose to spend half an hour reading during lunch or in the afternoon when time allows. Similarly, when the weekend is pretty open, I carve out an hour or two with the newspaper or articles I’ve been saving to read. If I end up on a train or plane by myself or with an occupied child, I also take out a book or these saved articles. I find that for me and my life right now, this takes away the pressure I used to put on myself to read daily while still allowing a meaningful and focused time for doing such.

Where you do it

Beyond a kind of transportation or library or nook in your office, finding a space at home can be useful. Some people like to read in bed; others fall asleep in this comfy space. Some people like a hard table to concentrate and place their book or computer on. Some use a desk. Some like the kitchen table. Others retreat into a beanbag chair with candles lit around them.

We had a beautiful corner with lots of light right next to a bookshelf that was a perfect fit for a new little couch. The best thing is that it is in a different room from the television and has a view of several trees. We decorated it with cushions from Indonesia that had been looking for a home. Now it is a sacred space — there are no toys or even electric outlets nearby. When I see fifteen or forty-five minutes ahead of me, I set myself an alarm (if needed) and retreat to the reading space.

If you find a place that works for you, it will be easier to get quickly into the mood and pick up right where you left off. You might even keep any of the reading tools you need in that area, whether the reading device/book itself or the pens and notebooks that you enjoy using with them.

Calibrating reading styles

You might be thinking — a pen and notebook? Surely we are not in school anymore! Others religiously use these items without allowing themselves time off from such rigor.

Reading purpose can vary depending on why and what you are reading. If it’s something for work or something you want to more deeply engage with, you might find it useful to highlight, make notes in the margins, and even write summary points as well as your own thoughts in a notebook or computer nearby. When I read with a pen, I read slowly. To stop and mark the page means to commit it to yourself and to read it again, both at that moment and in the future.

But even if you haven’t taken a speed reading course, you can develop a fast mode as well. This can be used for previews to see if something is worth your time, for ‘fun’ books in which you are mainly interested in the plot, or for reading content in between key areas you plan to read more slowly. Fast mode might also be used when you are re-reading a text, perhaps with the plan to pause at highlighted sections for the slow method. Two ways to achieve a fast reading mode is by reading vertically rather than horizontally and reading every third word, more or less.

The point here is not to consume more or less material in a sitting but to decide which pace serves you at this moment. I’m currently reading Paul Auster’s Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane at an intentionally slow, note taking speed despite its length of 738 pages since the prose is rich and the historical and literary references deep. The book I just finished at lightning speed is Ragnar Jonasson’s Blackout, a thriller that, although well written, simply made me want to find out each ensuing plot twist more than lingering on a turn of phrase.

Reading widely but selectively

It’s enjoyable and useful to open yourself to works in translation and works from a diverse range of authors. Even if you are not a literature teacher or scholar interested in the world-wide dialogue of literature, you can gain new perspectives and find interesting styles you may enjoy. You may also learn about another culture, perhaps of someone you know or a place or group you are somehow connected to. Additionally, you may have genres or text types you prefer. By branching out, you can expand your knowledge and reading enjoyment.

It’s a worthy endeavor to seek texts from everywhere, but can clearly make an even stronger overwhelming feeling. Sorry, there is no easy answer! Accept that making a few selections is better than none and better than too many. We can learn and enjoy reading a lot more by choosing a few outside our normal range. By reading them more carefully and really giving them a chance, you will get more from the experience than making a huge list to tackle. Still, you might find it useful to use the fast-read method at first to find a few new styles or perspectives that you like.

What’s most important is realizing you have this power. There’s been a lot published about the funneling of information online based on our preferences. Although it feels nice to agree with articles that pop up in our feeds or comfortable with books that are recommended to us on Amazon, it’s a powerful tool to step outside of this sometimes. Without it, we may fail to understand each other and fail to discover something that we love.

You can find wisdom in these unexpected places. As much as I love authors of literary fiction like Haruki Murakami, Zadie Smith, Henry James, Orhan Pamuk, and Edith Wharton, I have found great wisdom from children’s author Oliver Jeffers and cookbook icon Julia Child. Other books in translation have helped me understand cultures and moments in history, or at least one author’s perspective of them, such as Naguib Mahfouz’ The Thief and the Dogs, Herta Müller’s The Land of Green Plums, and Shokoofeh Azar’ The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree.

Start either with something you want to know about or a person or publication’s lists of works in translation or of a certain genre that they love. But never expect to read all the angles. Allow yourself to not know and be open to these revelations or discussion points through others who have taken those paths. Allow yourself the time and space to reflect on the themes of the texts you do select.

What did Dr. Abbas mean by trusting ourselves to read less? I think it must be that we know ourselves best. We can trust why and how we read as well as what text selections we make if they are all conscious choices. We can trust ourselves to be ok with not knowing many things and in allowing our own thoughts to be as important as all those thoughts out there in published form.

If you have methods of reading intentionally that work, please share them in the comments for others to reflect on.

Originally published with Better Humans on February 25, 2022. Thanks to editor Terrie Schweitzer.

A caveat: I’m a great believer in the power of the antilibrary or tsundoku, that is, the power of books in one’s library and piles that have yet to be read.

See, for example, this article about Umberto Eco’s antilibrary from Marginalia or this NYT article about Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb who first uses the word to discuss both Eco’s library and his use of it in describing Jonathan Swift’s discussion of a library. And according to Cambridge, the Japanese word “Tsundoku is the Japanese word for the stack of books you've purchased but haven't yet read.” I’ll let you explore this rabbit hole more on your own.

Jean Baudrillard - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

In this postmodern world, individuals flee from the “desert of the real” for the ecstasies of hyperreality and the new realm of computer, media, and technological experience. In this universe, subjectivities are fragmented and lost, and a new terrain of experience appears that for Baudrillard renders previous social theories and politics obsolete and irrelevant. Tracing the vicissitudes of the subject in present-day society, Baudrillard claims that contemporary subjects are no longer afflicted with modern pathologies like hysteria or paranoia. Rather, they exist in “a state of terror which is characteristic of the schizophrenic, an over-proximity of all things, a foul promiscuity of all things which beleaguer and penetrate him, meeting with no resistance, and no halo, no aura, not even the aura of his own body protects him. In spite of himself the schizophrenic is open to everything and lives in the most extreme confusion” (1988: 27). For Baudrillard, the “ecstasy of communication” means that the subject is in close proximity to instantaneous images and information, in an overexposed and transparent world. In this situation, the subject “becomes a pure screen a pure absorption and re-absorption surface of the influent networks” (1988: 27). In other words, an individual in a postmodern world becomes merely an entity influenced by media, technological experience, and the hyperreal.

And now, I shall soon go back to working in a school (while still writing). So it’s an interesting time for me to reflect on the reading experience I want to create for my students and our department.

Excellent article. I too enjoy the idea of an antilibrary! I don't know if this might be of interest to some of your readers, but 6 months ago I wrote about my methods for reading several books efficiently in a short time, not necessarily for enjoyment per se (in my case I had a week in which to review them): https://terryfreedman.substack.com/p/how-i-read-4-books-and-reviewed-them?utm_source=publication-search

Academic reading: My approach was to read the acknowledged expert's or experts' work but then seek out contrary views, because (a) the experts are often stuck in their views (I think Kuhn was more correct than Popper in his views of how orthodoxy gets overturned) and (b) the acknowledged experts get published and reviews by people in the same echo chamber. Not always of course, but I think that is definitely a thing.

At the moment I'm going through a Substack reading paralysis: there's so much good stuff to read here that sometimes it can be overwhelming. If you have a strategy for that, I'd love to hear it. Mine has been, so far, a bit of a cull of the ones I subscribe to

Thanks again for a great article

Thanks for this. Reading is so important and yet so overlooked by too many people.

Whenever I leave home, I triple check I have at least one book in my bag: what if I'm caught riding the train for 30 minutes or one hour and I have nothing to read? This is a truly SCARY thought.