Part of the ongoing series on Place and Creativity

I’ve been ‘home’ near Boston for over a week now and thinking about the way we may be influenced in viewing art due to our upbringing. I’ll have a conversation with a local artist and former college classmate in a couple weeks that will be shared with you all. I wonder, too, what our common study of art history by many of the same professors may have done to affect the way we see the world.

Today, I want to highlight more of the art that comes from Massachusetts, but I also want to focus on the idea of cultural spaces and their impact on both individual visitors and society. We’ll look at what a few theorists have to say on the matter, and I’ll ‘show’ you some of my favorite local museums, theaters, and concert halls.

Last week, we looked at American literature originating in Massachusetts; I mentioned several of the writer house-museums one can visit (one can also extend these visits to New England). Of course, there are other types of artists with these house-museums in my home state, such as Edward Gorey, Daniel Chester French, and Norman Rockwell.

And then there is a special home-cultural-space, called the Isabella Stuart Gardner museum. Gardner became interested in the arts on several trips abroad to try to move on from the death of her young son. She also met American ex-patriot artists on one of these trips, including John Singer Sargent and James McNeil Whistler.

Before her husband’s death, Gardner was already pursuing acquisition of the land that is now the museum and became her place of residence in 1903, marked with an opening that included a concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. She continued to collect art work for the next twenty years before her death, including several of herself by Sargent.

Gardner eventually died of a stroke in 1924 and left her house as a museum with endowment, but “stipulating in her will that nothing in the galleries should be changed, and no items be acquired or sold from the collection.” But whilst the walls may be stuck in time, the museum’s curators and directors have been able to continue to make it a living cultural space, as the original owner did a century ago. Concerts and lectures as well as weddings take place in the beautiful halls.

The museum’s Instagram page offers insight into the changing nature of this relic, one that a liberal thinker and traveler like Gardner would likely be proud of. It includes discussion of the museum on land once belonging to the native Massachusett Tribe and shows events for children as well as a diversity of people:

The caption the Gardner Museum’s Instagram post above reads:

Join us in two days for a conversation in honor of Juneteenth and exploring the project A DEAD NAME THAT LEARNED HOW TO LIVE by @goldenthem_ . This Neighborhood Salon Luminary poses the question, “What is possible when Black queer & trans folk are allowed to bridge, beacon, be?”

In this way, a cultural space brings many kinds of arts and people in dialogue. By inviting people in, the museum makes its famous paintings (and furniture and architecture) come alive and take on new meanings of their own.

Theorizing Cultural Space

Now, despite all the techniques for appropriating space, despite the whole network of knowledge that enables us to delimit or to formalize it, contemporary space is perhaps still not entirely desanctified (apparently unlike time, it would seem, which was detached from the sacred in the nineteenth century). To be sure a certain theoretical desanctification of space (the one signaled by Galileo's work) has occurred, but we may still not have reached the point of a practical desanctification of space. And perhaps our life is still governed by a certain number of oppositions that remain inviolable, that our institutions and practices have not yet dared to break down. These are oppositions that we regard as simple givens: for ex- ample between private space and public space, between family space and social space, be- tween cultural space and useful space, between the space of leisure and that of work. All these are still nurtured by the hidden presence of the sacred.

- Michel Foucault, "Of Other Spaces," 1986

Foucault asks us to question space and its use; how does it allow the mind to inhabit? How does it encourage an anti-discourse to society? Whom is let in?

A great article titled “Measuring a Sense of Belonging at Museums and Cultural Centers” in Curator: The Museum Journal explores the way cultural centers have historically limited inclusion, the ways that they may move beyond it, and the reasons it is important for the advancement of society:

Museums1 are not known as bastions of diversity. Historically, they have been designed by the few for the few….One of the pernicious symptoms of social exclusion is a feeling of not belonging to a place or experience. Having a sense of belonging is a fundamental need for human happiness and mental health (Maslow, 1958)….But the responsibility to fit in does not reside with the guest. It is a marriage between guest and museum, which imposes a powerful influence of its own. With their missions embedded into an academic, artistic, political and cultural firmament, the institutions carry extensive societal capital, expectations and baggage.

“Sustaining Culture and Creative Spaces” likewise questions the elitist aspect of cultural spaces and ways this reality or illusion can be broken down to provide greater access.

When have you felt especially connected or disconnected to a museum show or event? What, if anything, did the museum do to include (diverse) visitors in the experience? Is this not what educators (should) do to help all students access the learning by making it meaningful and accessible to all? How can a museum curator (a type of educator) work effectively with an imagined audience?

A further article to help consider the ways articles in museums, whether permanent or transitory, may be cultural goods and cultural capital that is both affected by society and influences it is: “Cultural Institutions Studies: Investigating the Transformation of Cultural Goods” by Werner Hasitschka et al in the The Journal of Arts Management Law and Society.

Other projects work with young people on a more global and dynamic approach to cultural spaces, such as this one in Basel: Cultural Spaces and Design Project. The project is part university course, part interdisciplinary project to make the practices of design, internationalism, and education integrated.

Museums

Even as a kid, I always loved visiting museums. Not just the children’s themed ones, although those are pretty great, too. In Boston, the Science Museum is very hands-on; my best memory of it is spending the night there for some kind of scout trip. Hmm. Seems really strange in retrospect…but I also remember the lightning machine show…and still remember the storm survival techniques I learned there.

Anyway, I’m talking more about the art museums. My dad, a chemist completely ‘science guy’, has long loved bringing us to art museums. We used to drive for three days to Minnesota to see relatives, and he would always find several museums en route for us to visit, such as the Art Institute of Chicago or the Anton Art Center. When we entered, I would be lost in a new world, amazed at the beauty you could discover there. As a kid, you just look and that helped me to form my own way of appreciating and understanding art.

But even when we weren’t traveling, we would visit local museums of which there are many for a small city and state, perhaps because of all the universities. We spent a lot of days at the Museum of Fine Arts as well as the Gardner and Institute of Contemporary Art. There was also the Harvard Fogg museum and other shows at Tufts or small galleries. My parents continue to be members of the MFA and I try to benefit whenever I visit home.

What I find interesting in looking not just at local art collections, but art reflective of the place around it, is the way it might change our perception of that place. As Alain de Botton discusses in The Art of Travel during a trip to Provence where he also viewed Van Gogh’s paintings of the surroundings:

After Van Gogh, I began to notice that there was something unusual about the colours of Provence as well. There are climactic reasons for this. The mistral, blowing along the Rhône valley from teh Alps, regularly clears the sky of clouds and moisture, leaving it a pure rich blue wihtout a trace of white. At the same time, a high water table and good irrigation promote a plant life of singular lushness for a Mediterranean climate….The combination of a cloudless sky, dry air, water and rich vegetation leaves the region dominated by vivid primary, contrasting colours. (p. 197, Hamish Hamilton edition, 2002)

For example, my husband (and many others I know) are not so enthralled at the prospect of snow storms (a staple of Boston winters), but I adore them. Not only for the possibility of skiing or sledding or ‘snow days’ (as a kid or a teacher) but also for their beauty.

Perhaps I am unfairly swayed by the art of snow. All of the paintings discussed in NPR’s “These Artists Will Change Your Mind About Winter” are housed at Boston’s MFA and a replica of Childe Hassam’s At Dusk (Boston Common at Twilight), 1885-1886 hangs on my wall. Somewhere during my upbringing, I made snow into a living art.

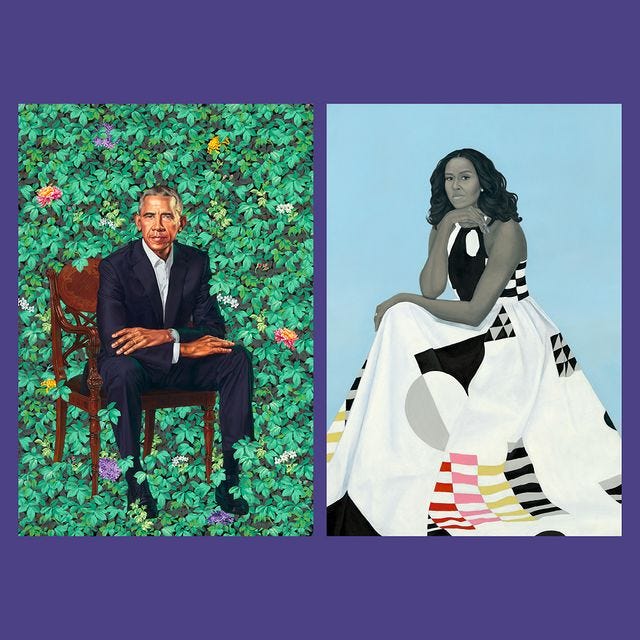

On this trip, I’m going to the MFA to see the Obama Portraits Tour, the works of Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald. I’ve seen a couple of Wiley’s works at Art Basel before; the pop of the pigment combined with the full treatment of the subject — as if their inner light comes to the audience — is magic. I imagine seeing his work of President Obama will have an even greater aura to it.

Western Mass also has many cultural spaces thanks to the universities, both concentrated near Amherst and Springfield and spattered throughout, as well as the visitors from New York City, looking to find both greenery and a continuance of constant culture.

MASS MoCA is the large scale museum of contemporary art in North Adams. I recall visiting on a trip with my mom to see universities (non-Americans, this is something you do in high school whenever you have spare time). I was mind-blown by the vastness of the project that includes: “music, sculpture, dance, film, painting, photography, theater, and new, boundary-crossing works of art that defy easy classification.” Their website About page goes on to explain: “We thrive on helping artists make work that is fresh, forward-looking, and engaging of the mind, body, and spirit…but we also believe that both our guest artists and audiences should enjoy their time with us.” They seem to have the idea of these exchanges with the audience in mind.

Here’s a list of the top 12 museums in Boston and a more inclusive list of museums and galleries throughout Massachusetts.

Theaters

Museums can be theaters as well, not just in their use of space as a venue for a dramatic production but in their use of the theatrical in presenting ideas and cultural artifacts to an audience.

Karen Vedel explores this idea in “Theatricalization in the Cultural History Museum” in Nordic Theatre Studies:

I argue that their impact on meaning-making ultimately relies on visitor participation and is produced self-reflexively in the engagement with the immersive environments, the audio-narratives and the displayed objects. The effects of the participatory involvement are enhanced by the requirements on the visitor to move in and out of doorways and navigate around fellow visitors through narrow passages. Among the effects of the immersive environment and its spatial design is the ability to call into play visceral sensations and multisensorial involvement.

Massachusetts is home to many theaters of different kinds. Not only do some Broadway shows make their way up to New York’s little cousin for a while but the city also has its own productions, especially in Cambridge at the American Repertory Theater and other venues in Central Square. The Opera House is ornately decorated, rivaling European opera houses.

To understand the power and effect of dramatic theater, I often turn to Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt, such as his discussion in “Invisible Bullets” (pp. 786 - 99, Literary Theory: An Anthology, Rivkin and Ryan). In this essay, he discusses the way not only Shakespeare’s plays and the Globe Theatre expressed views on politics in a powerful way for all of society to see but also other theater of the Elizabethan time as well as today. In a discussion of Henry V, he says:

Power belongs to whoever can command and profit form this exercise of the imagination. hence the celebration of the charismatic ruler whose imperfections we are invite at once to register and to ‘piece out’ (Prologue, 23). …Power that relies on a massive police apparatus, a strong middle-class nuclear family, an elaborate school system, power that dreams of a panopticon in which the most intimate secrets are open to the view of of an invisible authority - such power will have as its appropriate aesthetic form the realist novel; Elizabethan power, by contrast, depends upon its privileged visibility. As in a theater, the audience must be powerfully engaged by this visible presence and at the same time held at a respectful distance from it. (p. 798)

Of course, cinema theaters came from modern play houses which came from ancient Greek amphitheater (and/or perhaps from India and China). You can read a decent overview of the history with visuals here. More specific to the development of the cinema house, a history is traced in this journal article from Kevin J. Corbett: “The Big Picture: Theatrical Moviegoing, Digital Television, and beyond the Substitution Effect” with a hypothesis that digital television will never fully replace the movie theater due to people’s desire for a communal viewing space and experience that is all-encompassing. That is, although we are asked to be quiet in the theater, we will all experience the art together without distractions (ideally, unless, say, you fall asleep or your date keeps whispering in your ear to try to impress you with their knowledge of the allusions…’that’s just like in —, isn’t it?’; anyone else with this experience?). (Oh, and eating popcorn doesn’t count as a distraction as it is instead a reminder of the communal experience.)

What is true of all these spaces is a live audience, even after live performers and then live musical accompaniment is taken away, a film in theater creates a cultural space where we share in the art before us.

The play between theater and the real is a highly discussed one; Baudrillard makes a case for its fakeness or at least its depiction of an idea society that could never exist (see “Symbol Exchange and Death” p. 493-4 in Literary Theory: An Anthology, Rivkin and Ryan).

The Brattle in Harvard Square shows classics and indie films and has its own “unofficial film school” podcast (you can read about its foundation here). Around the corner, the local AMC used to show The Rocky Horror Picture Show every Saturday at midnight for 28 years until it shut down just a year ago.

Cinema houses have become a luxury to attend and historical places to keep up, even taking donations to keep them alive. The pandemic seems to have put the final plug on theatres after years of dwindling attendance, thanks to the ease of cinema at home. On the other hand, it made us aware of the collective experience we lost, causing a spike in attendance in summer 2022.

In a discussion of film digital release dates for Video on Demand platforms (V.O.D.) in determining “cultural endurance,” The New Yorker speaks with filmmaker Alex Ross Perry:

Perry worries that a modest financial success helped by video on demand may still prove a cultural failure. A real success, he argues, is a film that endures in the popular imagination, not just one that quickly earns back its million-dollar budget. As he sees it, putting movies in theatres still plays a big role in establishing that cultural endurance.

Theaters also have to keep up with the times. There’s a tiny movie theater in Lexington within walking distance of my parents’ house. I wanted to both support the cinema and give my parents an anniversary treat with a gift certificate, but I was told through an archaic online contact form that I could not purchase such certificate online. Luckily, nearby Arlington’s Capitol Theater had a simple online purchase process and is a historic arts center itself, dating from 1925.

Some parts of these old theaters, you don’t want to change. Another that has lasted the times is the Wellfleet Drive-In Theatre, which is a cool destination if you spend a summer on Cape Cod.

In a similar way that de Botton found a new appreciation for Provence through Van Gogh, we can see Massachusetts reflected in film and therefore influencing our understanding of place.

There’s the Jaws series from Martha’s Vineyard (as I discuss in The Sea) then many Boston-based films utilizing the mafia history, such as Martin Scorsese’s The Departed (2006, a reinvention of Hong Kong-based Infernal Affairs, 2002). Whitey Bulger and the Winter Hill Gang made Boston a space of imagination through the many true and mythical stories about them.

There are areas of Boston known for crime and poverty. Other films like Ben Affleck’s Gone Baby Gone (2007) and Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River (2003) also focus on these elements. I was able to see the latter film when I first moved abroad to Paris and despite its neo-noir elements, it oddly made me feel close to home and nostalgic. It was probably a very different experience than most had with it!

Here’s John Ulrich from South Boston quoting Gwendolyn Brooks to discuss many of his friends who succumbed to suicide and drug use as well as South Boston Survivors, his charity to help local kids “get into art or other things” that would help them:

The above video is part of Robert Pinsky’s Favorite Poems Project. A great project to recreate with students. Two of my other favorite videos are Evans Jones on “The Song of the Banana Man” and Lina Yiang on “I’m Nobody! Who are you?”.

South Boston, or “Southie”, is also the setting at the start of Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting (1997), with authentic Boston accents from Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Along with Affleck’s brother and Mark Wahlberg, films with these Boston natives are much easier on the ears for locals.

The film above, of course, moves over to the Harvard part of Boston (well, Cambridge) - identified as preppy, yuppy, snobby…whatever you want to call it. This is a great scene showing some of the conflict between different areas and mindsets of Boston.

The Social Network (2010) also takes place in and around Harvard and touches on some of these themes. To experience more of the Massachusetts film myriad, I recommend: adaptations of Little Women, Coda, Knives Out, A Civil Action, adaptations of The Crucible, Patriots Day, Manchester by the Sea, The Fighter,

There’s also a totally original film by Tom McCarthy you might enjoy for the way it portrays the power of journalism. Spotlight (2015) is a dramatization of The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team of investigative journalists. It highlights the way they exposed the sexual abuse scandal of the Roman Catholic Church in Boston, which was and is a very powerful institution and part of the local culture.

Concert Halls

Of course, there’s a lot more to the arts in Massachusetts than the literature, film, and art highlighted here and on Tuesday’s newsletter. There’s also a rich history of classical music at the Boston Symphony Hall, Tanglewood (out West in the summer), and Jordan Hall (home of New England Conservatory), fantastic concerts at Fenway Park (where one normally sees baseball) or House of Blues, and many other places of performance.

Most people would agree we can’t recreate live music at home through record players, videos, or Spotify; isn’t it the same with film or dramatic theater as discussed above? Each music space creates its own culture of experience.

The more intimate (but notoriously loud) Mama Kin Club was owned by Aerosmith who would also make surprise appearances there. Their goal was to help unsigned bands get recordings and signings there. It had the aura of the coolest place in Boston in the 90s…but closed in 1999 just before I would have been allowed in without a fake ID.

Perhaps the coexistence of different types of music (as in other cities) but in their distinct cultural spaces makes way for new music.

Of course, concert halls are on the streets, too, and there are plenty of street musicians as well as festivals on throughout the cities of Boston and Cambridge. Even without the best acoustics, there are benefits of reaching more people and clearly a much cheaper gig to put on.

The streets have character here. They are more European to many, because they were made in large part before having cars in mind. The bricks, tiny passageways, hilly backstreets, and different look throughout the four distinct seasons make these streets places where artists might flourish.

In reality, cultural spaces can be everywhere, from the nature trails surrounding Walden Pond or Emily Dickinson’s haunts in Amherst to the city streets of Acorn Street in Beacon Hill or Harvard Square (and the contrasting gated campuses or interiors of the university’s spaces).

It’s wonderful to see that cultural spaces are being supported by the new Mayor of Boston, Michelle Wu. Her team is focusing not only on preservation but also accessibility, in theory bringing creative spaces to all neighborhoods of the city. In this way, what we see on the streets may reflect the inspiration and mentoring that people can find in the workshops, museums, theaters, and concert halls they deserve the privilege to attend.

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

My hometown was a cultural desert, particularly when I was growing up, and my parents were never interested in (and never encouraged my sister and I to go to) museums, concerts, etc. So I'm mostly self-educated in that respect.

To this day, though I listen to music daily, concert-going is not really my thing. I became a movie buff when I was in college, and art is a more recent passion.

This is a piece I wrote about Tokyo cinemas. https://giannisimone.substack.com/p/the-last-picture-show?s=w

Club 47 / Club Passim has amazing musical tradition and history. Betsy Siggins (https://www.bennionkearny.com/betsy-siggins-club-47-bob-dylan-and-joan-baez/) was there for it all and helps run Folk New England (https://folknewengland.org/).