17. Self Portraits

How reflecting oneself is much more than narcissism (yes, even selfies)

Part of the ongoing series on Identity and Power

I took a painting class in college as part of our Art History program, and one thing we had to do was paint ourselves. Somehow the pose I chose inadvertently put my armpit at the center of the composition, and so it hangs in my parents’ basement. Don’t worry; I will not reproduce it for you here.

Still, it was a useful process and made me think about the purpose of depicting ourselves when there are so many other worthy subjects out there. Our professor told us that every painting we produce would be a kind of self-portrait, a window into our souls. In fact, when I painted a copy of Lucien Freud’s ‘Girl Reading’, I thought it looked just like my sister. Well, according to the class, it really looked just like me (who happens to look a bit like my sister). Maybe I just look in the mirror too much and it became the painting? Maybe I inadvertently chose something that already looked like me? Or maybe we find ourselves in other images, other portraits, and are able to learn from this discovery?

Why do we seek to capture ourselves? I think it must be mainly about understanding our identities, both for the purpose of knowing ourselves better and for sharing these pieces of ourselves with others. One could also argue it’s vanity. Or perhaps a kind of unhealthy obsession of the self.

My later self portraits become body parts - legs separated from body, sometimes upside down / an arm (attached to my head, but this was secondary). It could be labeled as something to do with cubism or feminist painting. I guess it’s because I also spent so much of my time doing sport, looking at these body parts to function at their peak. Icing them or heating them up. Stretching and massaging them. Without meaning to, I looked at them all the time and, really, you only see your face when you look in the mirror.

I felt like my muscles were something to be proud of — so I drew them. I also liked the different shapes you could make and they way you could think about how to use your appendages in different ways; like, how am I different when I’m upside down? Why can’t adults still do acrobatics? When will my muscles next fail me?

Anyway, it may also be because I was not amazing at painting faces! I’m not sure; I haven’t tried all that many of them. Or because I wasn’t quite sure who I was yet. (Am I now?) Maybe I was afraid of capturing something of my self that was beyond me.

This all occurred in the pre-smartphone-selfie era. Would our class’s gallery have looked very different a few years later, because of this phenomenon of ubiquitous faces?

Selfies get a bad rap, but several psychological studies have found that taking selfies actually produces positive feelings about oneself and general happiness. However, this good feeling can become an obsession, even addiction.

Has it always been like this — with classic self portraits, I mean? We all know Vincent Van Gogh had mental health problems and many know that he produced a huge amount of self-portraits. Were they helping him stay sane or see beauty in himself despite his problems…or did they contribute to his downfall? Or, were they simply witness and document to what Van Gogh went through?

Van Gogh is widely seen as one of the masters of the self portrait; here are several others. His study of shape and color and light are always powerfully beautiful, in my opinion, aesthetically. But there is also something in the expression that suggests a search for his own humanity.

There is a beautiful poem by Derek Walcott titled “Self Portrait” (1980) about Van Gogh:

The loneliness of Van Gogh.

The humbleness of Van Gogh.

The terror of Van Gogh.

He looks into a mirror,

and begins to paint himself.

He discovers nobody there

but Vincent Van Gogh.

This is not enough.

[...]

no. Nobody there,

not Vincent Van Gogh,

humble, frightened and lonely,

only

a fiction. An essence.Walcott looks at these self portraits as psychological experiments from the artist himself. It is as if he sought a type of therapy by finding himself in painting and instead pealed back the layers of self to expose, through the paintings, his loneliness and fears. One might argue that we all share these fears, and perhaps the appeal of his self portraits is more than the beautiful brush strokes, but the imagination of the hand that made them, one that could be our own.

Chuck Close is another favorite self-portraitist (and portraitist) of mine. In a similar way to Van Gogh, at first his paintings seem like color and shape studies. The squares of color that make up the faces in huge scale draw us in. The experience is that we want to step close and then far back for the full experience. I think this mimics the way we understand ourselves and others. We can look at the minutia; but then who is it in front of us? Are they kind? Have they had difficult experiences? Are they open to our friendship? Do they have questions about themselves?

Below, Big Bird and some kids like at a “painting of Chuck” by zooming out slowly:

His work captivates kids partially because of the discovery element. There are different layers to the work they look at and, ultimately, they are faced with a person they can connect with as well as imagining becoming artists themselves.

Maybe there’s something childlike that wants to draw…ourselves. Maybe it’s a way to figure ourselves out. Or be proud of ourselves. Or discover something that makes us unique.

The act of encountering

I had the privilege of teaching art a year ago to children. A joy which I have talked about before, though it also had some pains (I love teaching teenagers, but I’m not really comfortable with a room full of kids under 12!). The experience taught me a lot.

We started with self portraits in the older years, grade 5 and 6, which became my most memorable unit. We learned about facial proportions, shading techniques, working with pencil and oil pastel. The children did a great job of observing and trying things out, while being open to starting again if something didn’t turn out right.

I could see they were taking this project seriously and wanted to help them push it a step further. So I decided to add a layer of master-study as well as pastiche to the assignment. After some classroom inquiry work, we went to the nearby world-class art museum (just a walk down the road; what a place to teach art), to experience some of the self-portraits and portraits in person. We looked, discussed, questioned…and then the students sketched in their notebooks for about an hour, sitting on the floor or benches. They wanted to stay longer.

It was evident that these faces impacted the way they saw themselves. Later, through selecting one or two artists to pastiche in some way in their own self-portraits, the students drew on creative symbolism or aesthetic techniques to say something really powerful about their identities. Pastiching let them dig deeper and experience the self in new ways. For example, a one student added a natural background like those of Frida Kahlo to demonstrate her own interactions with the Swiss mountains. Another, also interested in Kahlo, made somewhat of a unibrow to show her transition to a puberty. One used Picasso’s ‘blue’ self portrait (1901, at the Picasso Museum in Paris) to consider how she feels in the middle of winter. Another used “Seated Harlequin” (1923), not a self portrait but a study from our trip to the museum, as inspiration for herself after ballet practice.

It’s one thing to learn from making art out of yourself, about yourself; it’s another to learn from other’s self portraits. Do we simply learn about the artist themselves? This could be a worthy enough undertaking. To understand an individual is to value their life, their culture, their journey. But it can also tell us about more than that one person. It can tell us about different elements of context and about shared human experiences.

It’s certainly not the same effect as looking in the mirror. And rarely would I say it flatters the artists; instead it discovers or uncovers something. Let’s take the blue Picasso - it is as if it is a layer of him. He appears to protect himself from something - the cold? His own fatigue? Failure? But he also does it by looking directly at himself (in the creation of it) and the viewer (in the end effect). Although confident in the stature he creates, I sense a relay of some of the suffering he holds — as we all do — in this blue-tinged layer of his self.

Perhaps this is what makes the self portrait worthy of being hung in a gallery: it gives us much more than autobiographical information. It can be a beautiful aesthetic, a political message, or a study of the human experience, just like other kinds of art.

The photographed self

Wolfgang Tillmans is an incredible portraitist with a lot of press this fall due to his big exhibition at New York’s MOMA (on until January 1, 2023). The German photographer is known for his representations of intimacy, nightlife, and queerness. The museum’s description of its show starts with Tillmans’s words: “The viewer...should enter my work through their own eyes, and their own lives.” He believes in an independent engagement with his work, including many portraits of others as well as himself.

Osman Can Yerebakan for The Art Newspaper describes a transcendent experience from encountering Tillmans’s portraiture:

The pictures seem to breath, move and even dance. The images seep into our minds' eye like the water, sweat and tears that Tillmans always loves to show us—in our most naked encounter with photography, we change too. Facing the essence of capturing moments in his photographs, we remember why pictures exist and our eyes are cleansed from saturated downpour of snaps on screens and off.

Although Tillmans is perhaps most famous for depicting queer identities and artists in his work, a review of the show in The New Yorker also places the city itself and his work as a multi-media artist at the forefront of his appeal, which could add to our previous conversations about The City as Text and Soundtracks:

[Tillmans’s] gaze on the city is a knowing one, whether it is turned on a downtown It Girl (a portrait from 1995 of Chloë Sevigny holding an electric guitar), an image of rats creeping around, or the Spectrum, a queer night-life venue formerly located in Bushwick. He also makes music, and the new exhibition includes videos accompanied by the soundtrack of his first full-length album, “Moon in Earthlight.”

Returning to the people themselves, these images of faces and bodies are exquisite — sometimes celebratory and other times sad. But what fascinates me in the context of self portraiture are several of his works titled as ‘self’ with hardly any of his body present. [Although here is another “August Self Portrait” (2005) that does capture his full figure, plainly dressed and at ease, as if to say, “Hello, here I am. What do you think?”]

I can’t find a freely sharable photograph of either I’m going to talk about right now (on commons or through Instagram; if you see one, please let me know so I can add it to the article). You can look at the article linked above to see “Lacanau (Self)” (1986) and at this article from Der Standard for "Lüneburg (self)"(2020) (also reproduced in the New Yorker article below).

“Lacanau (Self)” was taken decades before smartphones. It is from the perspective of the artist’s gaze, looking down on his light pink t-shirt, Adidas shorts, and leg/foot, walking in the sand. The image created appears abstract and looks like a study of color and shape. Lacanau is in Médoc, between Bordeaux and the Atlantic coast of France. We went to that region this past summer for a couple of weeks to enjoy the sea, the oysters, and the wine (which is delicious, by the way). But we also found something else: rather than an uptight gathering of people at the shore who simply wanted to add to their wine collection, there were extremely large naturist camps and a very alternative, eclectic feel. I can understand why Tillmans wanted to capture himself in this spot and why a light pink t-shirt with tanned skin captures the mood.

"Lüneburg (self)" is more intimate, if you look closely enough, as it depicts the artist in bed, taking a photograph of his phone, mirroring himself in a small rectangle, presumably the camera of a video call. The receiver of the call, however, is only shown as a light pink (again) duvet, creating (also again) an abstract shape in the rectangle within a rectangle. The phone is held up against a water bottle on top of a plain off-white table of sorts; it reminds me of my son’s old high chair tray. From 2020, I think we all had scenes like this. Because we have to zoom in or look very closely to even see Tillmans (who is then still behind a big camera lens), it perhaps emphasizes the enclosures around us all during the pandemic. It is as if Tillmans is saying, “Look, I am still here, though I may be hidden. I’m capturing this moment in history. And I’m capturing my place in the world in this strange moment.” Or maybe he’s saying he’s disappearing.

What do you think it says? And how did you capture yourself during the pandemic? Many of my photos of the time are of my son growing up, learning to walk with more confidence, completely unaware of the uncanny nature of the empty city surrounding him, or selfies of us doing something at home. Some are also screenshots of me with friends and family on zoom/whattsapp/houseparty/facetime/meets calls, trying to also capture this moment in time, selfies through another screen not unlike the one above from Tillman.

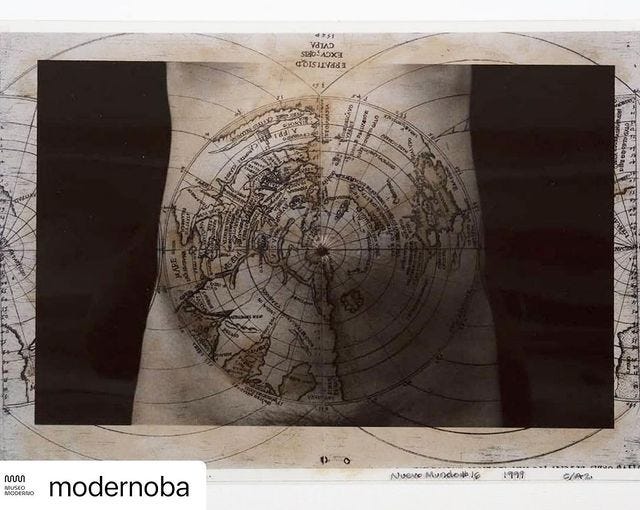

Also exhibited at MOMA this fall as part of a different show — “Our Selves: photographs by women artists from Helen Kornblum” — is Tatiana Parcero. She is a Mexican photographer working primarily with self portraits. Her work places body and nature, as well as drawings from ancient civilizations and colonial mapping, in the same frame and even put in physical interaction as an overlay on her body. Here is a link to further reading in Spanish from Deborah Dorotinsky Alperstein that places her work within a cultural context.

Her self portraits create something like ephemeral tattoos, using her body as the canvas but also as the natural medium.

jdc Fine Art who shows her work says: “ Her visual explorations harmonize and repetition of Parcero’s own figure through different series affirms the singularity and plurality of human the experience- one of many; all are one. The body has evolved as universal symbol, unit, or container connected to and composed of everything.” This goes back to the idea that although her photography is extremely intimate in terms of her own body and its interaction with history and nature, the effect is universally human, not only for her culture but for anyone. How have our bodies been shaped by histories around the world? How are we a part of the map of the world, however miniscule in scale?

#selfies

What’s the difference between a self-portrait photograph and a selfie? Typically we consider selfies to be self-portraits on smartphones and not necessarily of an artistic nature. But there is crossover and differences of opinion, as outlined on the Getty blog; this particular definition is offered from the curator of the Getty’s In Focus: Play, Arpad Kovacs:

The self-portrait and the selfie are two separate, though at times overlapping, efforts at establishing and embellishing a definition of one’s self.

Qualities like medium specificity, deeply rooted histories, and traditions (or lack thereof) that define these efforts only superficially differentiate the two. What has greater weight is the selfie’s inherently replaceable and even disposable quality. If after taking a picture of oneself the results are unsatisfactory, it is easily forgotten and replaced by a new picture.

The self-portrait, whether it is a carefully composed study or created in haste, often contains more decisions than could be easily erased. Calling a self-portrait by Rembrandt a selfie is not only anachronistic, it also negates the carefully calculated set of decisions that created the rendering.

This does not mean that selfies cannot be self-portraits, or that selfies by nature require the opposite of calculated intent. An artist could choose to represent him or herself through selfies; however, self-portraits don’t immediately signify selfies.

So any selfie on Instagram, my selfie platform of choice, could be a self-portrait. According to Kovacs, it depends on the intent and, perhaps, the editing and curation process. As these elements are invisible to the viewer, are we also able to decide what is worthy of portraiture status? Something that looks spontaneous, for example, might be extremely thought out or edited. Or must we discover through documented interview of the process by the artist? And must we believe them?

There’s a connotation that the act of taking selfies means you are vain or self absorbed. ‘Oh, I don’t take selfies!’ is the mark of a balanced, confident, selfless person…isn’t it?

The Chainsmokers’ #SELFIE has a scathing and humorous look at the act of narcissistic selfie creation:

I like their take, and have definitely rolled my eyes at the kind of behavior they depict here, but I don’t think this method of taking selfies is the only one. What if selfie-taking could instead be something uplifting despite Buddhist ideas that letting go of the self is the best way?

I’m not saying that not taking selfies makes you anything at all other than somebody who’s not into it. But I do think that if we think of each selfie as a type of self-portrait sketch, there can be positive purpose this act of creation. Maybe that’s just because I like taking selfies sometimes, and I’m not afraid to admit it.

I’ve been going through a bunch of photos on my Apple cloud, which is why I was looking at the pandemic photos I mention above. Just pre-dating that, I came across many selfies I took as a new mom, during my year at home on maternity leave. The experiences and emotions flooded back to me — extreme fatigue, extreme love, confusion, isolation, contentment, joy, frustration, what-felt-like-failures, boredom, who-am-I moments, am-I-still-strong? poses. What was really interesting to me was that upon viewing the selfies, I recall many of the feelings and wanting to capture those moments later for myself, almost like a private diary. By studying them later, what I saw was much more positive than at the time. I think that in many, I felt like: “This is so hard and nobody sees me!” and in hindsight, I see a lot more strength, contentment, and dynamic shifts in perspective.

It’s hard to name exactly what it is in the photos that I see — I don’t know if it’s love or strength that I see instead weakness and isolation, but it’s something there that tells of the powerful journey. I mean, I still see the fatigue clearly under my eyes and in my skin, but something else shines through from behind it.

Maybe a self portrait is a kind of forgiveness. It’s like saying: here I am, my whole self. Through this act I am validating/loving/acknowledging myself.

Is that what Picasso was doing as well? Or did he think himself a superstar whose face needed to be hung in museums? If you look at the blue self portrait of him again, I think you’ll see something much more raw and vulnerable than that.

A selfie or self portrait is also a kind of power. We choose the image others see of us; we choose how we want to see ourselves. We can make this image available to the entire world, whether they choose to view it or not. There is some bravery in exposing oneself in this way through a moment of intimacy with oneself.

A supermodel, for example, now has the power to create her or his image rather than be the object of a photographer and curator all the time. Their social media can tell a counter narrative, if they prefer. Although of course at times there will be PR and agents whispering in their ears about what would be best for their image, in other words: what sells. If they do control their own accounts, they really do have full say, although they could lose work because of it. (i.e. Bella Hadid’s support of Palestine on Instagram leading to a loss of work.)

There are quite a few articles on this discourse, including the BBC’s look at influencers’ effect on the industry, an examination of the drawbacks from Vogue, models’ power over businesses on social media, and a look at wider representation of models (shape, culture, race, etc.) through self promotion.

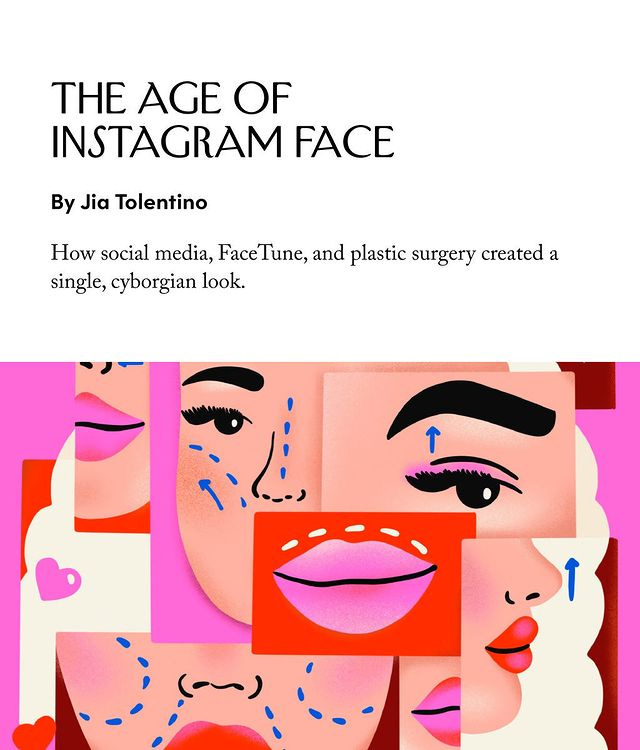

However, must of us have also read of the dangers of the idealized body on Instagram and other platforms. Although photographic touchups and different types of plastic surgery have been around a long time, the current phenomenon, according to The New Yorker, is worse because it is in front of us everyday and its difficult to know what’s real anymore:

Social media has supercharged the propensity to regard one’s personal identity as a potential source of profit—and, especially for young women, to regard one’s body this way, too. In October, Instagram announced that it would be removing “all effects associated with plastic surgery” from its filter arsenal, but this appears to mean all effects explicitly associated with plastic surgery, such as the ones called “Plastica” and “Fix Me.” Filters that give you Instagram Face will remain. For those born with assets—natural assets, capital assets, or both—it can seem sensible, even automatic, to think of your body the way that a McKinsey consultant would think about a corporation: identify underperforming sectors and remake them, discard whatever doesn’t increase profits and reorient the business toward whatever does.

The article posits not only problems created with body image due to Instagram’s images but also an increase in plastic surgery directly linked to what people see on Instagram, which happens to be doctored photos anyway.

And what kind of photos are they? They make people thinner, more ‘white’, younger…and sort of strange if you really stop and look:

“It’s like a sexy . . . baby . . . tiger,” Cara Craig, a high-end New York colorist, observed to me recently. The celebrity makeup artist Colby Smith told me, “It’s Instagram Face, duh. It’s like an unrealistic sculpture. Volume on volume. A face that looks like it’s made out of clay.”

So you have filters and angles to look a certain way and then in real life people are trying to copy these filters with plastic surgery. Makeup, too, is sometimes used for these effects and has been used for centuries to mask abnormalities or enhance features. Makeup can be fun, like an artist’s toolkit, unless it is used to cover dissatisfaction and sadness. Is your makeup a mask or a celebration? The answer can be subtle and can change on a daily basis.

Long-form self portraiture: films & novels

Even if we don’t take selfies, all of our feeds are in some ways self portraits — what about even our curation? Is a Spotify playlist we create not a type of portrait of ourselves, at least for a moment in time? Can we find the person there among all the music, as if rising above it like a spiritual intertext? In longer versions of self portraits, we see much more than faces staring back at us. Perhaps it can answer some of the questions above, or alternatively make them more complex, which is really a more accurate depiction of our own complexities.

Another work like the photographer Parcero that also makes great use of place and the body is a self portrait of a country, as proclaimed in the title: Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (Ma'al al-Fidda, Ossama Mohammed & Wiam Simav Bedirxan, 2014). The International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) writes:

While in political exile in Paris, the Syrian filmmaker Ossama Mohammed received an extraordinary Facebook message from the Kurdish teacher and activist Wiam Simav Bedirxan from Homs. “If you were here with your camera, what would you film?” Mohammed edited the material Simav shot herself in the besieged city together with excerpts from “1001” cell phone videos of heavy shelling and aerial bombardments. Blood flows – a great deal of blood. Citizens are tortured and executed, and no one can turn a blind eye any longer. But this is more than just a devastating documentary about the tribulations of ordinary Syrians. The reflective commentary also demonstrates what cinema can mean in the face of war.

In a way, it is a self portrait of the filmmakers, their views and cuts of a tragedy in their homeland is also a part of themselves. However, the use of the film work from many other phones shows a collective approach to capturing a place in time. It is a “self-portrait” rather than “portrait” because the images and voices come from within, come from parts of the country itself.

María José Alós’ An Appropriated Self-Portrait (Mexico, 2014) offers a self-portrait of herself (rather than a place) but likewise through a montage of images. As MUBI says:

The simple premise of this unique, female self-portrait—a search for one’s self through faces, dialogue, and images from films—becomes a complex exploration of identity and its construction through others. This work is a mesmerizing, empathetic kaleidoscope of cinematic appropriation.

She also uses clips of others, such as Winona Ryder in Girl, Interrupted (from 53:00), to show herself. Others include Claire Danes, Nicole Kidman, images of the universe, and a landscape including geysers. The effect is that we must attempt to create an idea of her (or ourselves) through the variety of images and sounds.

Another self proclaimed self portrait film is by Agnès Varda: The Beaches of Agnès (2008) —

Varda starts with a short discussion of her name (first Arlette after Arles, where she was born; she changed it to Agnès at age 18), which seems like an important thing to discuss when trying to understand the self.

On the beach, she asks those who will help her recreate scenes from her life to look at a mirror to see the camera; there is therefore a heightened awareness of the framing of things and the dreamlike quality of film that is both a reflection of real life and not. She also sticks old photos in the sand, as if creating a mini gallery that interacts with the actors and the natural surroundings in harmony.

Her self portrait is a journey: the places seem to tell the story as much as the people. The film partly explores her genealogy – visiting her childhood home, exploring the denial of Greek ancestry by her father. It explores space and memory. There is the beauty of the old home’s tiles, radiators, glass captured through the camera; they had to flee at the start of WWII; this is both a trauma and a joyous adventure.

Though the film is declared a self portrait, she can’t help being interested in others. The film is also about neighbors, the man living in her old home, feminist activists, and, especially, her husband who died of AIDS: the filmmaker Jacques Demi. The mosaic of people in her life helps us also understand the filmmaker, through her gaze, through her love.

Because Varda also writes this and her other films as an auteur, they are each in some way a self portrait of her. Writers do this, too. Milan Kundera says in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (France, 1984):

The characters in my novels are my own unrealized possibilities. That is why I am equally fond of them all and equally horrified by them. Each one has crossed a border that I myself have circumvented. It is that crossed border (the border beyond which my own ‘I’ ends) which attracts me most. For beyond that border begins the secret the novel asks about. The novel is not the author’s confession; it is an investigation of human life in the trap the world has become. (p. 215)

According to Kundera, then, and if others write or make films like he does, then any text is a kind of self portrait, or at least an imagined version of the self that may or may not be realized.

The last line above demonstrates the idea that the more we attempt to capture our unique selves, the more we paradoxically may find a universality of humanity that only differs because of the world’s ‘traps’, that is, contexts perhaps limiting the assertion of our identities. In the case of The Unbearable Lightness of Being set during the Prague Spring, this is also specifically about governmental control on our bodies and our ideas.

Further reading & viewing:

The New Yorker on Janice Guy’s photographic self portraits

“Joanna Hogg’s Self-Portrait of a Lady” on the filmmaker’s self-portrait film: “The Souvenir”

James Joyce: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

André Aciman: Alibis — essays on elsewhere

Paul Auster: Winter Journal

In the last text mentioned here, a memoir, Auster writes in the second person as if the self-portrait were never intended for outside viewers. It gives the language a feeling of intimacy, allowing him to level with himself and be comfortable with not always knowing how he feels about something. I think we are all doing something like this with any kind of self portrait. It is an exposure.

It is also an understanding that while we can attempt to piece together the narrative of our own lives, we can never fully understand that of another. In this case, he talks at length about his mother who recently died:

On the other hand, even though you happen to be her son, you know next to nothing yourself. Too many gaps, too many silences and evasions, too many threads lost over the years for you to stitch together a coherent story. Useless to talk about her from the outside, then. Whatever can be told must be pulled from the inside, from your insides, the accumulation of memories and perceptions you continue to carry around in your body—and which left you, for reasons that will never be entirely known, gasping for breath on the dining room floor, certain you were about to die. (p. 132)

No portraiture can tell the full story of one’s life. But maybe it can capture some of these pieces Auster is so afraid of losing, or that he’s already lost, of both his mother and himself.

The passage brings up another point, that the body holds memories and the body is a composite of people we love rather than just our own self. In this way, any of the self portraits discussed above are also creations of those who love the artist. There is a communal element to the selfie, even if one creates it alone.

Do images of yourself or the process of creating some image of yourself change the way you view your own narrative? Can it help us to discover missing elements or memories?

Feel free to add a link to your own self portraits in the comments. Or, give us your scathing opinion of selfies! We’d love to hear all sides.

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

What a fascinating discussion on the study of self-portraits; I love the way you introduce the idea of the selfie as self-portraiture. Your selfie's during lockdown and of your early days as a new mother are a wonderful way to capture a place and time for the future. I have to confess that I am not very good at taking pictures including selfie's, and usually rely on my kids to take them of us as a family!

I have been thinking a lot about these ideas of images within the media lately also in my own posts, as well as identity and how it is expressed and understood.