Part of the ongoing series on Beauty and Creativity.

Every city is beautiful to me (from outside its borders), just as all talk of particular languages' having greater or lesser value is to me unacceptable. -Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 1927-40 (p. 458, Belknap Press)

Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their

discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and

everything conceals something else.

-Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, 1972 (p. 44, Harcourt)

So here I am in New York. The mega city. The elusive city. The City of Dreams. Whatever you call it, it’s a whole thing. Not a place, but a perspective or way of being…or maybe a being itself.

I’ve never lived here but keep coming back. Perhaps it’s the distance and time that make it an imaginary ellipsis for me, built upon memories, cinema, and literature much more than reality. It dances in my mind with other urban life, all compartmentalized by place or culture or emotion.

The beauty of bombardment and of layers of (hi)stories, of magical encounters with the everyday and with all kinds of culture(s)…these beauties wistfully fly around me in the autumn wind, whispering into my ear and awakening my soul. The soles of my shoes make a rhythm as I carve my way through, blending with the sounds of this urbanity.

There are so many pockets to this city. These days, I spend a lot of time in Brooklyn, only because my friends have moved there. It’s a different world from when I used to visit Leela in the East Village or my sister in Astoria. But then, it’s all the same city. It’s all part of a weave of buildings, streets, restaurants, museums, offices…and, of course, people.

I come from a suburb outside a small city and first went to school in a small town on the coast of Maine. But since then, my life went all urban, like it does for a lot of people. Boston, Paris, Milan, Hong Kong, Vienna, London, Basel…that’s where the jobs are…and the apartments and the people.

But, oddly, we can find solitude in the city. Sadly, many people find extreme loneliness, too. It doesn’t have to be that way. Sometimes learning to navigate the city’s possibilities can help us to see and to choose what’s for us. Or sometimes it’s the city itself that should be helping others by reading itself, understanding what it’s spaces mean for its denizens, and where people might fall into the gaps.

How many of you live in cities? Is it a necessity – i.e. for a job – or do you live there because there’s something you love about it? What kind of city is right for you? How big? How international? When you travel, do you enjoy heading to a city for its culture or do you prefer to ‘escape’ to the countryside?

How does it feel when you enter a city? And when you leave it?

New York oozes life. Sometimes, though, it makes me so switched on that I have a hard time relaxing while I’m there. As much as I love it, I feel relieved that I don’t have a million choices of cuisine and music and shopping at my fingertips when I leave. That could be because I don’t live there.

I guess when I first moved to Hong Kong, I had a similar kind of overwhelmed and excited feeling. Even though I loved all the shows and catch ups and food and art and eclectic fashion, escaping felt nice. If you live in a city, you find your escapes within it as well, don’t you? Many New Yorkers like ‘the park’…but there are other spaces, too. Maybe it’s just a friendly local café. In Hong Kong, I could get on a hiking trail within ten minutes from my flat in central. In Basel, a teensy tiny city by comparison, my home is a fifteen minute walk to the center, yet it’s an escape. I guess all homes can or should be, but I mean it’s really surrounded by green and it’s also pretty quiet (although we do hear youth walking home at odd hours of the night, reminding me life is happening on many levels and at many hours here).

Maybe it’s being able to escape that lets us not only appreciate but also understand the city on some kind of deeper level. After I read a book or watch a film, it takes a little time to separate myself from the experience and think about it. Same thing with a city. The city is a text, after all, and it’s one that’s being rewritten every day.

So there’s probably a trillion things you could say about cities, because they’re each unique and they’re each uniquely experienced by residents and visitors. But what we can do is try to organize ways of investigating the city. It can help us to understand the city as a text.

No, I’m not an English teacher trying to take the fun out of cities! Ahhh! Hear me out. Through understanding, we can gain more awareness of our impact on it and vice versa. Could it be more fun this way? Imaginary possibilities at every turn…

And maybe through these analytical skills or themes and motifs that can slowly develop over time, we can realize our own identities more fully by allowing transformation and finding justice within the spaces that nurture us, whether home or restaurant or library or event hall.

Today is for framing and we’ll come back to cultures and personalities of different places around the world later, building on some of the ideas we start here. Today is for finding a common starting point of what cities have to offer us while at the same time beginning to understand what makes a city unique.

Reading and writing the city

What is a city? And what is a text?

ThoughtCo. has a little overview of what makes a city vs. a town, and it varies greatly by country. It may be population or local governmental structures or, historically, whether or not there is a cathedral (in the case of England) or even a wall that surrounds it.

Cities, of course, vary greatly by size and global impact. There are markers or rank, like Alpha, Beta, and Gamma cities; explained well here. Only London and New York make the Alpha++ ranking and Alpha+ is made up of Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, Beijing, Dubai, Paris and Tokyo.

There’s also an interesting blog called Alpha City by Professor Rowland Atkinson, Chair in Inclusive Societies at the University of Sheffield. Interesting he doesn’t live in an Alpha City, but he is not so far from one of the only two Alpha++, which is probably useful for his research. He deals with a lot of issues, such as: gentrification, where taxes go, representation through journalism, and “what contribution each of us makes.”

Or, if you prefer to measure your cities by skyscraper, this website places Hong Kong at the top, followed by Shenzhen just over the (disappearing) border with China.

How are they all cities and how are they each unique? I’m talking about culturally. But, of course, that is influenced by everything else.

The word city comes from the Old French cite (town or city) and the Latin civitatem meaning: “citizenship, condition or rights of a citizen, membership in the community," later "community of citizens, state, commonwealth.” Of course the idea of ‘citizenship’ as someone who belongs to a nation goes back to city-states; ironically, 19% of the world’s foreign born population lives in cities, so many are likely not citizens by modern definition.

A text, well, is anything that can be read. Literary texts are of the ‘written word.’ Other texts have their own languages as well. It’s something we teach in high school English these days…the language of film, graphic novels, multi-media…and there’s so much more: music, paintings, photography, architecture, tattoos, fashion…all these have their own languages of performance and lexicons of analysis that are also in flux. They are dynamic because text types evolve as reflections of the individuals and cultures that create them and because they work among intertextual, international networks.

There is a language of cities. We can read the walls of a city. The bricks, street art, windows…they all tell stories. They tell us who was there and who is making claim. They tell us what is being kept in or kept out. We can read the signs; there are literal signposts as well as symbols of signification everywhere. People walking down the street each tell a story as well, both visibly and invisibly.

The smells and sounds tell stories, too. Anything close to the smell of wood faintly burning reminds me of the Paris metro. Some have tried to map smells; this designer, too. There are many languages in a city and there is the host language. New York is home to as many as 800 languages, some held intact through diasporic neighborhoods. In Hong Kong, I constantly heard the interplay of Cantonese, English, and Mandarin/Putonghua. These languages mean different things culturally, politically, and economically.

There’s also big, visible scale language of the city: the architecture and green spaces. The movement of streets. Do you feel different on a huge avenue and in an alley? We even use different prepositions to place ourselves there.

My late, wonderful advisor at the University of Hong Kong, Dr. Esther Cheung, created a course called: “The City as Cultural Text.” Although Hong Kong was Dr. Cheung’s starting point for her investigations of culture and urban studies, her perspective was global and her expertise ran deep in literature and film from all over the world. The course as well as her work on ‘the city’ more generally, looked at the play between global and local frames. This was something she helped me to do with my project between Hong Kong and New York; one that was also built upon understandings of world migration, cinema, and urban studies.

But Esther’s understanding of the cities was not limited to the matrix of local and global; she was also interested in both the culture of the everyday as well as collective experiences of traumas or events.

Dr. Winnie Yee, also from our department, wrote a posthumous article about Dr. Cheung’s work, titled: “Between crisis and creativity: Esther M. K. Cheung’s study of the everyday” (2016) in the Journal of Urban Cultural Studies (another good resource for this topic in general). As Dr. Yee summarizes:

By analysing textual practices such as film aesthetics and metacultural criticism, Esther M. K. Cheung developed a unique approach to Hong Kong and other global cities. Her interest in urban culture was not confined by geographical boundaries. In a unique and remarkable way, Cheung analysed the intricate relationship between everyday life, creativity, and moments of crisis. Her readings of, and intense preoccupation with, understanding cities have inspired scholars to seek the abandoned and hidden small events and narratives of our everyday life.

We’ll look more at all of these elements later on when looking at Hong Kong, and I’ll also do some writing about ‘culture of the everyday’ in relation to a few interesting theorists in a few weeks..

Today, I’ll look at texts that write the city and contexts that allow us to read the city to create a frame by which we can further investigate urban spaces as we look at particular places in the future.

Urban imaginary

We can look to artists for inspiration about the idea of a city.

Poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire is an interesting perspective to see Paris from, but he is also a philosopher of artistry within urban life. In “The Painter of Modern Life” (III, 1863, see also Jonathan Mayne translation on p. 682 in Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism, second edition) he discusses this city observer’s relationship with the paradoxes of urban life:

For the perfect flâneur (saunterer), for the passionate observer, it is an immense joy to take up one’s dwelling among the multitude, amidst undulation, movement, the fugitive, the infinite. To be absent from home and yet feel oneself everywhere at home; to view the world, to be at the heart of the world, and yet hidden from the world, such are some of the least pleasures of those independent spirits, passionate and impartial, that language can only inadequately define.

Still observing Paris some 120 years later in 1983, Chilean Roberto Bolaño wrote about a “sinister” sky hanging over the city in his novel Monsieur Pain (review from Ursula K Le Guin):

Like a mirror hanging over the hole, I thought. But we could never know for sure. An indecipherable tongue. I urinated against a wall, profusely. I was tired; I felt wretched, alone, and confused in the midst of a labyrinth that was far too big for me. (p. 77)

Reflections of both filth and beauty can be witnessed in literary accounts of cities, often within paragraphs of each other, sometimes finding beauty in the filth or vice versa. It is as if we are lost in a “labyrinth,” willingly allowing all kinds of humanity to reach us. Although the city is a place of possibility, it is likewise an entrance into letting go of your path and allowing the labyrinth to of our world’s truths to take over.

When we look at NYC specifically we’ll come back to the labyrinth with Teju Cole’s Open City, Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry, and Paul Auster’s City of Glass. And I cannot think of labyrinths without thinking of Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Garden of Forking Paths” (1941), even if the subject is not specifically urban:

I imagined a labyrinth of labyrinths, a maze of mazes, a twisting, turning, ever-widening labyrinth that contained both past and future and somehow implied the stars. Absorbed in those illusory imaginings, I forgot that I was a pursued man; I felt myself, for an indefinite while, the abstract perceiver of the world. (p. 122, Collected Fictions, 1998)

In Venice, the Borges Labyrinth garden is inspired by this story and promises “reflection, awe, and intimate recollection.” CBC Radio also has a fascinating look at “Borges’ Buenos Aires: The Imaginary City,” discussing, for example, the way “being blind allowed [Borges] to see the world in unfamiliar ways.”

Do you allow yourself to get lost in city streets? What do we gain when we turn off Google Maps? How do un-navigated journeys mimic our thoughts? When I lived in Paris, smartphones didn’t exist and the city is not on a grid like NYC. I had a tiny pocket map that got me anywhere I wanted to go. I went by foot whenever I could, discovering little shops or nicely painted doors along the way. Sometimes, I had a friendly interaction because I was lost. I would ask someone for help and in a few minutes, we shared cultural exchanges on street corners that could became mini films inside my head, forever accessible and shifting in memory.

Other creative geniuses seemed to throw themselves into these mazes, even with its dangers, to expose the hidden beauties in their art. In “David Bowie Was Really Singing About City Life” by Feargus O'Sullivan in Bloomberg’s CityLab (2016), he looks at the way Bowie echoed Baudelaire’s solitary navigation of the city:

Few major music stars have proved so fascinated with city life, both its freedoms and its occasional desperation. As a boy from a grey suburb who tried to forge a creative life in the big city, Bowie didn’t just have dreams that chime with many people. For fans, his career and music actively planted the seed of that dream, creating a template for those who sought the city’s freedom to liberate themselves—and who found that, when they arrived, they often got more than they bargained for.

Cities run like a seam of coal through Bowie’s music. It’s not every musician, after all, who writes songs about urban revolutionaries, a 1970s DJ lonely in his nightclub booth, and the movie theater as a (failed) site of urban escape, or who writes instrumental music evoking the streets of an Eastern Bloc city. Not uncommonly, his songs’ voices adopted the persona of a lonely urbanite.

This summer, I read a strange and beautiful novel that felt like a journey in the author’s memories between shared traumas (i.e. terrorism in Nice) and personal reflections (waking up in a hotel room with his wife). In To Walk Alone in the Crowd (2021), Antonio Muñoz Molina writes of several cities, interweaving a fictional journey of the mind that is pieced together as memories of city experiences. He collapses time in Paris:

To walk through Paris with nothing to do and no one to meet after a day’s work is to be here on this precise evening in June and simultaneously to remember it years or decades later, when things that are hazy or even entirely invisible in the present will appear in the crisp, irrefutable outline of their historical becoming. (p. 71)

And in Hong Kong, he imagines an encounter with Portuguese artist Vhils about the global nature of cities and the way “[d]estruction is part of creation”:

A world that all big cities have in common, including Hong Kong. No matter how far apart or how ethnically different two cities may be, in the end there is always soul and cement. That is why he set up his second studio in a Chinese city that sometimes resembles London and at times Beijing. (p. 104)

Artists working between cities can find truths in the connections and in the echoes of memories — both personal and collective.

Pedro Correa photographs cities as if he were painting them. The Spanish painter working in Brussels travels to many large cities for much of his work. From the photographer’s website:

Excerpt from interview for Villas Magazine, by Kunty Moureau

"When approaching Pedro Correa's work, one must go beyond what lies in plain sight in order to appreciate the mission he has undertaken: to reveal the beauty of cities where it is least apparent. What he calls "impressionistic photography" is a moment of truth that cannot be grasped at first sight."

We can make projects of cities collaboratively as well. Artists can encourage others to create in hidden spaces.

Nigerian-born London-based poet and dramatist Inua Ellams began a project called The Midnight Run to create through discovering small places in the city and sharing between people:

The idea behind the Midnight Run is simple, to negate the frenzy and hysteria of mass media and reality t.v. for actual reality; for the simplicity of walking and talking. To reclaim the streets and rediscover a city after dark, to inhabit its confines of glass, concrete, steel and structure, as a child does a maze; with as much innocence and wonder as is natural.

After studying James Joyce’s Dubliners, a short story collection of people and places of Dublin culminating with the more famous novella The Dead, my students have created their own multi-media pastiche: Hongkongers and Vienners. Students are able to pastiche style and respond to themes from Joyce’s work while adding their own photographs or drawings of once invisible places and people. They simultaneously investigate their own relationship with the city and create a collective experience at a certain point in time. Hopefully, they also learn something about classical literature and sublime writing style!

Further related reading:

Patricia Novillo-Corvalán connects Joyce, Borges, and Bolaño under “Transnational Modernist Encounters” (2013)

“Imagining the City: The Difference that Art Makes,” Judith Vega (2013)

“The Anthropology of Cities: Imagining and Theorizing the City,” Setha M. Low (1996)

And what about making a ‘City’ from sand, from seemingly nothing, rather than creating art from within a city? This is what Michael Heizer has done for fifty years in the desert. It has recently opened, but the artist claims it is not done. This piece of ‘land art’ is only available to six visitors a day. What is a city without people? Is it a vision of a dystopian future or does it mimic ancient cities discovered by modern humanity? The absence of people suggests the city has a life all its own from the stone and sand, carved into beautiful aesthetics. But of course, the design is by a person, an artistic vision. What humanity is left in the infusion of the design?

The (post)modern city

Modernity has shaped the city differently. It has added skyscrapers, making vertical cities, sometimes on the outskirts of the historic city, like Paris’ La Défense. Early skyscraper rivalry between Chicago and New York has given way to many more in the Gulf and China especially, although the American cities still certainly make the cut. Architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, I. M. Pei, and Zaha Hadid have changed the shape of the city.

The buildings are not just architectural beauties (or eyesores, like the Montparnasse tower) or (phallic?) symbols of power; instead they can be practical ways to expand and improve urban life. Bloomberg looked at the pros and cons of adding skyscrapers to cities in 2016. Building taller buildings can also be better both the environment and providing access and equality, as this Atlantic article argues.

I am awed by these large buildings and love to journey up to the top of them when allowed (and when there isn’t a big line); I learned to live in their shadows in Hong Kong, welcome on a hot summer day. But in Hong Kong, we could also easily hike up above — within the city — to look down on these buildings, reminding us of the power of nature and allowing us to see them as players in a cultural construction.

Modernity’s layers of creation and destruction in the city is a theme explored by Benjamin in The Arcades Project and by many others looking at a ghostly city as well as Anthony Vidler’s ideas about the “Architectural Uncanny.” Orhan Pamuk begins his memoir Istanbul with themes of this urban doubling and strangeness, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is probably the most famous example. We’ll come back to these ideas with London as well as ideas about the Freudian double and doppelgängers in general.

So, how has Postmodernity changed the shape of cities? We can’t assume we are past ideas of ‘modernism’, even though the ‘post’ suggests after; the two are in play with each other in a kind of ongoing conversation. Modernism’s key features (as artistic movement) are generally reduced to individualism, experimentation, symbolism, absurdity, and formalism. Postmodernism is instead characterized by “broad skepticism, subjectivism, or relativism; a general suspicion of reason; and an acute sensitivity to the role of ideology in asserting and maintaining political and economic power.” One might see modernism as a response to tradition in light of industrialization while postmodernism is a breaking apart of truths we had believed to be true in the wake of world (nuclear) war and (the more uplifting) revolutionary movements in the 1960s.

I’ll explore these as artistic movements later, including a discussion of Toynbee’s use of the term and French post-structuralists. But in essence, we can think of Modernity as a historical time period from the late nineteenth century to the second world war, and Postmodernity either defined as starting after WWII or 1968 when we think about the shape of cities.

To add to the increase in the globalization of cities, Postmodernity has added digital screens to our realities. Our screens both reflect the cities we see, often making the invisible visible and live mapping one’s whereabouts, and document the urban culture before us.

Additionally and pre-dating our smart phones, screens have become part of the cityscape. New York’s Times Square is perhaps the most famous example and you might also conjure up images of Tokyo, but sometimes unexpected juxtapositions have the greatest impact, like this recent Samsung ad in Barcelona:

With digital screens, the signs of the city become more complex, because the speed at which visual and sound change in front of us is unlimited. Jean Baudrillard calls this a part of the hyperreal, a world without a clear origin, constantly in flux. In Simulacres et simulation (French [Simulacra and Simulations] 1981), Baudrillard talks about the cinema of the hyperreal that makes a sort of perfect, absolute reality, but one paradoxically grounded in constantly fluctuating signs (p. 75).

How does your urban experience fluctuate due to encounters with moving signs? Do advertisements speak to you on the metro? Do you look down at your smartphone as you walk, occasionally? Has your cashier been replaced by a digital screen? Whose screens are you on — captured inadvertently in people’s photographs or on surveillance cameras…keeping us all safe?

In “Symbolic Exchange and Death” (pp. 488-508, ed. Rivkin and Ryan), Baudrillard discusses the “indeterminacy” of postmodern society (pp. 490-1) and its ubiquitous truth:

The city is no longer the politico-industrial zone that it was in the nineteenth century, it is the zone of signs, the media, and the code. By the same token, its truth no longer lies in tits geographical situation, as it did for the factory or even the traditional ghetto. Its truth, enclosure in the sign-form, lies all around us. It is the ghetto of television and advertising, the ghetto of consumers and the consumed, of readers read in advance, encoded decoders of every message, those circulating in, and circulated by, the subway, leisure-time entertainers and the entertained, etc. Every space-time of urban life is a ghetto, each of which is connected to every other.(p. 502)

Cinematic cities help us to imagine these types of framing between modernism and postmodernism in an imagined world.

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982, with sequel Blade Runner 2049 in 2017) are two frequently cited films in the realm of urban studies.

The films both investigate the duality of creation and destruction in the city. How can the city represent future hope as well as dystopic visions? When does innovation and technology go too far? When do buildings, robots, and screens take over our humanity?

In States of Emergency: Urban Space and the Robotic Body in the "Metropolis" Tales (2008), Lawrence Bird writes (pp. 127-8):

One of the most ubiquitous and disturbing images is indeed, an image that comes close to defining them – is the apocalyptic destruction of the city, with a human or humanoid figure at the epicenter. Very often this figure shares in the destruction of the city: it comes apart as the city does. This mutually experienced destruction implies more than just a catastrophe. Whether we are aware of it or not, bodies and cities act as each other’s limits. On the one hand cities and buildings, as they shelter and enclose us, articulate a series of important distinctions. They mark a boundary between the spaces of the individual and those of the public. They afford a distinction between the space of citizens (often associated with the human) and the space beyond citizens, beyond civilization (the realms of the inhuman). On the other hand, our bodies in turn place limits on the city. Architecture and urban form take the human as their measure, literally and metaphorically. The shared destruction of these mutually delimiting figures -- human and urban architectures – implies a modern crisis in what it means to be human and what it means to dwell together in a community.

If you’re interested in Blade Runner as a postmodern text, definitely take a look at Giuliana Bruno’s “Ramble City: Postmodernism and ‘Blade Runner’” (1987), at least as a starting point. She hits on a lot of ideas about pastiche, schizophrenia (as a term used in postmodernism; ie by Fredric Jameson), history, artifact, and more. This is the conclusion, which will make a little more sense if you read the rest of it (!!):

A tension is expressed in Blade Runner between the radical loss of durée and the attempt of reappropriation. This very tension, which seeks in the photographic signifier the fiction of history and which rewrites history by means of architectural pastiched recycling, underlies as well the pyschoanalytic itinerary. An itinerary suspended between schizophrenia, a fragmented temporality, and the acceptance of the Name-of-the-Father, standing for temporal continuity and access to the order of signifiers.

Liminal space

But what about the invisible layers of the city? Does it have a soul? What is lurking in the emptiness?

A city is made of different texts that fit together to make a massive one, a living one. The in-between spaces, literally and metaphorically, create a liminality of experience. The crossing of thresholds and gaps can be places to ponder and to dynamically thrive, or they can be greatly detrimental.

At best, cities are spaces of creativity, where the individual is empowered to be who they want. At worst, they create entrapping black holes where the individual is lost. This is where spatial justice comes in.

Writers and artists have long loved the city. They lurk in its shadows, observing the others. Or they shine on its stages, calling out to be seen.

PKL “Morning in a Foreign Land” (city at the end of time, pp. 194-195, Cantonese and English versions, English translation by the author and Gordon T. Osing, 2012)

I wake to find heaven and earth indeed changed.

In my half-living in the mists the gone ones speak

and return to mist. I think of the ones we know

scattered about in the world, enduring storms.

A broken-off aftermath of words lingers at the edge of my mouth,

mixes with the new world’s sounds to make yet another language.

In a blue, clearing sky the torn clouds

scatter around the skyscrapers of this foreign land.

July 1991, Chicago

Calvino Invisible Cities

You can read Calvino talking about his book in a lecture later published in Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art:

What is the city today, for us? I believe that I have written something like a last love poem addressed to the city, at a time when it is becoming increasingly difficult to live there. It looks, in- deed, as if we are approaching a period of crisis in urban life; and Invisible Cities is like a dream born out of the heart of the unlivable cities we know. Nowadays people talk with equal insistence of the destruction of the natural environment and of the fragility of the large-scale technological systems (which may cause a sort of chain reaction of breakdowns, paralyzing entire metropolises). The crisis of the overgrown city is the other side of the crisis of the natural world. The image of "megalopolis" - the unending, undifferentiated city which is steadily covering the surface of the earth - dominates my book, too. But there are already numerous books which prophecy catastrophes and apocalypses: to write another would be superfluous, and anyway it would be contrary to my temperament. The desire of my Marco Polo is to find the hidden reasons which bring men to live in cities: reasons which remain valid over and above any crisis. A city is a combination of many things: memory, desires, signs of a language; it is a place of exchange, as any text- book of economic history will tell you - only, these exchanges are not just trade in goods, they also involve words, desires, and memories. My book opens and closes with images of happy cities which constantly take shape and then fade away, in the midst of unhappy cities.

Although the lecture is from 1983, it could have been written today. The conflicts with overcrowding and the environment are still there. What is beautiful is that Calvino allows himself to see the harsh reality of what cities can do — swallow up the earth as well as people’s dreams — but can also maintain an optimistic, imaginary vision of a happy urban future, where culture and art and internationalism (symbollically through the meetings between Kubla Khan and Marco Polo) can propel us further into a more peaceful and beautiful future.

[You can also look at Calvino’s book in relation to postmodernity specifically through the article “Postmodern Temporality in Italo Calvino's ‘Invisible Cities’” by Sambit Panigrahi (2017).]

These things at play create the liminal space or the ellipses that allow for creation:

Culture (personal and collective)

(Post)Modernity

Private/public space (spatial justice…)

(In)Visible

Past/Future (ghostly, imagined, machine, preservation)

Spatial justice

Spatial justice deals with the puzzle of space and the way that space is used. What is accessible for all? I don’t just mean private and public. What about spaces with illusions of membership? Streets just for this kind of person or that one? And shops? Family parks…clubs for the youth…basketball courts for the talented…signs for who is welcome and who is not…

Seeking Spatial Justice by Edward W. Soja (2010) explores this idea though case studies in Los Angeles that attempt to understand why and how disparity of city spaces affects people. He looks at urban housing, mass transit, spaces of culture, and other resources, arguing that “justice has a geography and that the equitable distribution of resources, services, and access is a basic human right.”

In order to investigate how “justice and injustice [as a product of geography] are socially constructed and evolve over time,” he begins with quotes from two other renowned scholars in the field:

Questions of justice cannot be seen independently fro the urban condition, not only because most of the world’s population lives in cities, but above all because the city condenses the manifold tensions and contradictions that infuse modern life.

-Erik Swyngedouw, Divided Cities, 2006

Just as none of us is beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings.

-Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism, 1993

So space and justice are also intertwined with culture, in other words, who we are.

My PhD was concerned with the urban space of the apartment, specifically of migrants, and the way it allowed or denied possibilities of identity assertion. These private apartments are in constant flux with the external spaces — especially through building ownership, public housing governance, outside space — i.e. what is going on on the street, and how the outer urban culture, traumas, and laws impact the person living on the inside of the flat.

David Harvey is geographer who deals a lot with philosophical questions of space and time. Here is a lecture from him on the Right to the City and Urban Resistance:

In an essay called “The Right to the City” (2008), Harvey sums up his views about the dynamic aspect of cities and identity:

The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from that of what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire. The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.

In “Creativity, Culture, Knowledge and the City” (2004), Peter Hall discusses the need for driven artists, youth, and talent from a variety of backgrounds within cities if these global places labeled as knowledge centers are to continue as productive forces. He describes the conclusions of several urban theorists who have suggested this sort of spatial justice, allowing ‘common people’ to live in the middle of the city, takes a lot of time and careful thought:

That conclusion holds if the aim is to build a truly creative city: one in which there are embedded cultures and networks of creativity. Of course, it is possible to create a substitute in the form of an instant programme to build new galleries, concert halls or museums. This is the construction of a city of cultural consumption, in the form of urban tourism, and it need not have much at all to do with the other deeper process, the building of a city of cultural production. Yet even the city of consumption may be a problematic enterprise unless there are certain preconditions in the form of existing facilities, existing artefacts, like older galleries or theatres or concert halls and d the populations that support them year-long. (p. 257)

Cities tend to have art schools and MFA programs, just as they have other types of educational schooling, but it is more difficult for an artist than a scientist or banker to make enough money to live in central London. Yet, we want art in the city; in fact, we equate it with the city. Are all artists doomed to struggle until they become the small percentage who ‘make it’ at the cost of perhaps their health or having a family?

The future of cities

There is a cool interactive multi-media on the Shape of Cities by National Geographic. How will they continue to change? What’s next? What can create more accessible and green cities whilst maintaining the cultures and awe of experience?

UN Habitat: For a better urban future – has a very cool interactive multimedia website; click to read the full 10 chapter report with some really sweet illustrations.

World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities seeks to provide greater clarity and insights into the future of cities based on existing trends, challenges and opportunities, as well as disruptive conditions, including the valuable lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, and suggest ways that cities can be better prepared to address a wide range of shocks and transition to sustainable urban futures. The Report proposes a state of informed preparedness that provides us with the opportunity to anticipate change, correct the course of action and become more knowledgeable of the different scenarios or possibilities that the future of cities offers.

Quartz’s “What’s next for smart cities?” explores the realms of digital layers and extended postmodern hyperreality that can positively impact cities. Apps are also changing cities. Mapping is occurring on a 4d level.

But there is also a return to historical architecture and preservation as well as a re-imagining of city centers in a post-pandemic world. Is the hope in a return to something else, something nostalgic or is it in a futuristic cityscape? This tension has been explored through fears and imagination since cities began.

There’s so much to consider —

What about global health and the spread of the disease? The New Yorker explored How Ecuador’s largest city endured one of the world’s most lethal outbreaks of COVID-19 and several films explored the impact of SARS on Hong Kong pysche as a collective trauma well before our recent pandemic.

What about the impact on the environment? Despite fears addressed by Calvino and others, could the city of the future be answer for efficiency?

Will we continue to expand the vertical cities in innovative ways, or consider instead more of the impact of space on the street level?

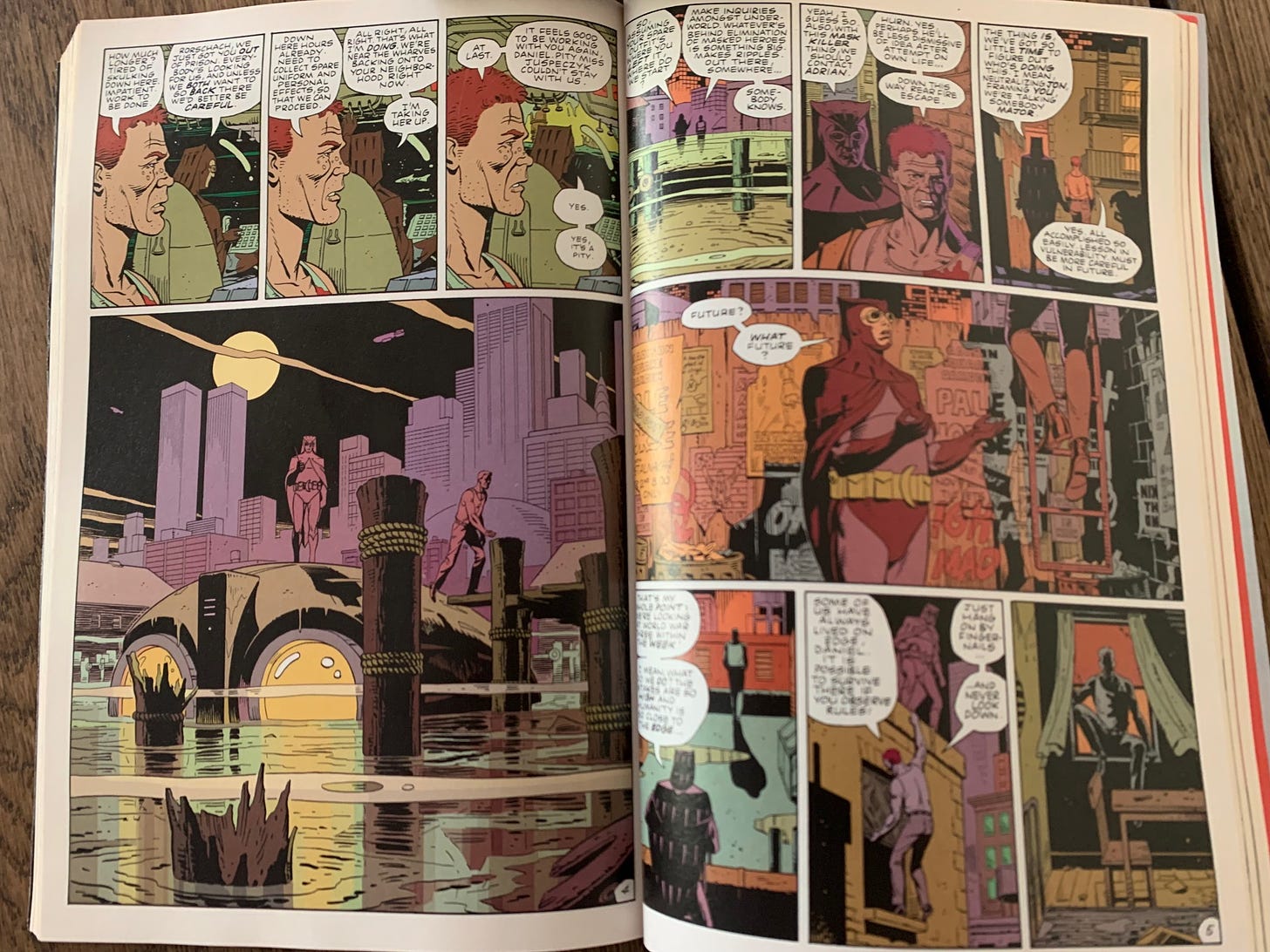

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ graphic novel Watchmen (1986, international edition for DC Comics - 2008) also deals with the existential question:

‘Future? / What future?’

We’ll keep exploring the concept of the city as we look at specific cities. They are all in conversations themselves and the way one evolves or is rooted in particular histories and arts may affect another.

In the meantime, tell us what the city means to you and what other texts help you understand the concept of urbanity.

Man, I’m exhausted, just like after a trip to NYC. Time to put the phone on ‘moon’ and get a little lost in the old streets of Basel. I hope I didn’t wear you out, too! :)

This topic could be covered so many ways, and you got to lots of them! A couple books / projects I like when I think about cities are Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs, Cityscapes of Boston by Peter Vanderwarker and Robert Campbell, and the photographers Charles Marville followed decades later by Atget covering Paris' 19th to early 20th century transformations which then inspired Bernice Abbott to create changing New York in the 1930s. The list goes on and on. All manage to pin down some part of the intangibles of cities. Oh, and LA Plays Itself is an amazing documentary showing how even when you're not making a documentary you capture documentary details.

Great topic, Kate. I love reading literature set in the city and always find it difficult to connect to books and films set in the countryside. I also love living in a city, and am lucky in that where I live in the UK is purported to be the greenest city in Europe, where the trees outnumber people - a fact I love! - as well as being right on the edge of the Peak District National Park, so there is plenty of greenery as well as urban architecture. It is also a vibrant university city (with 2 large universities) and we live right by one of them. It means that the city always seems to be in flux as the students leave and return, and it makes for a multicultural as well as multi-generational population.