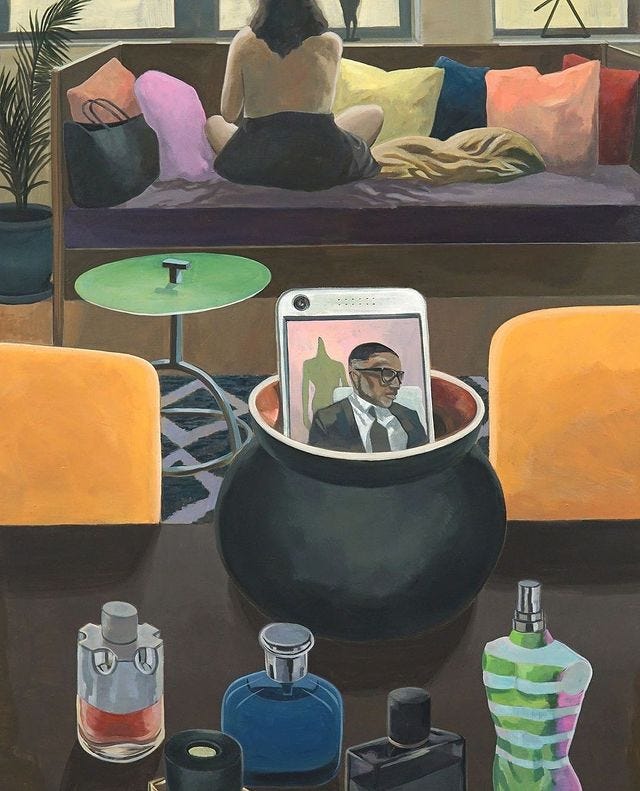

12. The Phone Call II (going digital)

How have changes in phone communication changed the way we experience reality?

Part of the ongoing series on Transformation and Representation

I was always late to the party with cell phones, smart phones, and roaming data packages. I guess I’ve always been trying to keep some independence from my phone (and also save a little cash when I was a student — again). But the inconvenience is that you can get left behind…limiting my online connection to being on campus or at home during my PhD meant that instead of calling or texting me to make sure I made it to a social event (these, of course, began changing at the last minute the moment we were able to pivot through our pockets), friends would continue to WhatsApp me (really the only acceptable communication in Asia) with confusion about my lack of data plan. Well, it saved me a bit of money, and that was scarce at the time, but not enough to make it worth it.

Before smartphones even, I was late to get a cell phone, but who needed one on a small New England college campus, especially when most of your friends either lived with you or were on your sports team? And you went to parties in groups, collecting and roaming together…or if you roamed apart, enjoying the not knowing of where you would end up. Isn’t it fun to be elusive?

When I think of literature or film about this period in one’s life, I imagine a post-2005-or-so one would simply be filled with different forms of online messages to convey narrative changes. But I graduated in 2002, just before Facebook was born in 2004. Like the world of Charlotte Simmons, we went (relatively) blindly about our days. Our “facebook” was a ten page white and black print out of our first-year class; you better hope you had a decent photo cause you were stuck with that for four years. Facebook has a lot of problems, but at least you can make your profile photo what you want; if you come to college with braces (yes, that’s me, and they weren’t the invisible variety at that time, my friends), you’re really going to want to change that photo when it’s possible. (Don’t pity me; I embraced the braces and bonded with Vinny #3, a big senior with the same metal apparatus who always seemed to be at the same parties and shared an affinity for the uniqueness of our mutual metallic disfiguration.)

If you also want to read about the state of theorizing phones and their social impact at that time, Hans Geser writes of these investigations from a Swiss perspective in 2004: Towards a Sociological Theory of the Mobile Phone. A lot of the ideas are still relevant, however. Perhaps they are even predictive of our normal now. Take this example:

The cell phone accentuates these contingencies because in comparison with the fixed phone at home. calls can hit receivers in a much broader range of different mental states, social circumstances and environmental conditions (for instance while being exposed to eavesdropping in a cafeteria or while driving a car).

Cinematically, this can be interesting investigation of the human psyche — in public vs private, and the way we are all part of a big performance.

For a follow up investigation from the Wall Street Journal, check out the video on how the iPhone changed us over 15 years. It looks at many angles, from teens asking why you would ever take your phone out of your hand but also those who hate selfies. Somebody conjectures: “We are just intermediating reality with this screen in front of our face” (13:00-05). Is it “everything you could possibly need in the palm of your hand” or is there “moderation needed”? The question is central to the documentary.

Anyway, after deciding to go back to a cushy salary at an international school rather than a scholarship or starting academic pay (there were other reasons, too, but the money influenced my phone use, which is why I only mention it here), I went all in and never looked back. I put a lot of limits on my phone use, but this isn’t a mindfulness or productivity post about how I get my writing done.

At the same time, though, I wanted to try everything out, partly because teaching these ‘new textualities’ of social media or podcasts was part of the international Language & Literature curriculum that I was teaching and partly because I was simply interested in understanding. I learned about Snapchat and Tinder (not part of the curriculum, but I was recently divorced!) and finally had enough data to share photos and videos whenever I wanted, creating a library of hundreds that would grow to many thousands in need of the forever-once-a-month-cost of iCloud Storage Upgrade after having a kid.

I had decided to embrace it and go all in. Some days I hate my phone, but isn’t my life also richer for it? I have culture and art and texts at my fingertips…and I can create all these things in my hand, too. It’s safer, too. Those college campuses are better with access to Ubers and friends, but there’s also access to online predators. Hmm. Some might say that’s like saying you shouldn’t wear your seatbelt because you might need to escape from your car. It does make us safer but we have to know how to use it the right way. The problem is that that’s changing all the time.

There are far fewer horror films building tension and suspense through calls on smartphones (unless they mysteriously lose a signal I guess). The magic and mystery of the old school phone has been lost. I’ve never even owned a phone like that despite my slowness to adapt — in college they were issued. I never bought my own. I often want to just throw my smartphone in a drawer for a day or two, but I think about using it when there is danger or being there if a teacher calls about my son needing help. Have we handcuffed ourselves or created a better world? I always come back to this question, usually deciding on the latter but still wishing to be more free.

Mobile phones and the culture of everyday life

It seems to me a lot of artists are slow to adopt the changes in phones over the last few decades. Maybe the fear is about dating their work too specifically, with changes being made so rapidly, things look old quickly, but not old enough to be vintage or retro. I haven’t found a great piece of research on this, so if you know of it, please send it my way.

To get back to artistry, let’s start with my 2014ish impressions: I enjoyed Instagram for its ability to curate beautiful things and memories. Twitter had some great intellectual and journalistic uses, which were great as teaching tools, but could be overwhelming. A great teaching moment was when the kids were shocked that hashtags actually had functions beyond humor (#canhashtagsbefunnyanymore?). I hated Snapchat and all kinds of ‘Stories’ at first, but then the hip teens told me why they liked it. ‘It’s more like an old phone conversation.’ Huh? ‘It’s so stressful when people can read your texts over and over again…these are like conversations, there and gone. Ephemeral!’ I love when my students teach me. This was deep.

I’m talking about a whole different world of online texts that we explore in different conceptual topics here. But I also use it to illustrate that while a phone is not a phone anymore, maybe there is a desire that it behaves more like it used to.

Quite a few sitcoms as well as some films use texts that pop up on screen. It allows for counter narratives and secret messages between characters. This happens on the French soap opera Plus Belle la Vie, for example, where affairs and sneaky teenagers are all around. BBC’s Line of Duty likewise makes use of texting between characters. Here’s a scene of ubiquitous secret communication. It’s highly useful in plot development since the subject of the show is the police unit investigating other police; there are many layers of truth.

Aesthetically, though, it looks stupid. And when others use it as part of the screen, often we miss it on our tiny home screens where most of us watch film and television now. Many articles explore why and how the screen seems to get texting wrong, such as this one from 2018 and this one from 2021. We’ve got to assume actors, screenwriters, and directors do a lot of texting themselves; is that the depictions are inauthentic or that smartphone use feels inauthentic itself to the human experience?

Many are simply leaving them out, because who wants to see these tiny screens on a big screen even if we use our phones all the time in real life? Who wants to experience love or heartbreak through texts? Who wants to understand the world through tiny videos? Well, loads of people. And I’m not saying they’re wrong. But literature and film are the opposite: they hold our attention to develop a story relatively slowly and to explore the nuances of humanity and cultures. You could argue against that statement with a lot of art that’s out there, but I guess I am thinking especially about the art of everyday life.

I think of a passage about “visual journey[s]” in Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life (1980, translation from French to English by Steven Rendall in 1984). He discusses the “cancerous growth of vision” in our society (p. xxi), and claims that a purely literary text allows for more imagination and growth. Would De Certeau consider a phone call – or even texts – more open to an active imagination and understanding vs. the visual of a Facetime call? Well, in real life, the visual Facetime is not (usually) some sort of propaganda or advertising or even simply art meant to tell us something. But if this Facetime were in a film or used as an image in a written text, it would contain more passive information perhaps. In any case, maybe we would not listen to the words of a phone conversation as carefully as we would without visual.

Baudrillard’s concept of the Hyperreal also seems to predict the strange realities we live in with smartphones creating a multiplicity of realities, so it is hard to know what is real life.

We use our phones everyday. Therefore, they are extension of our bodies. But this means that there are other forces potentially controlling our bodies. John Fiske’s famous essay on the everyday: “Cultural Studies and the Culture of Everyday Life” looks to Foucault:

Foucault argues that the mechanisms which organize us into the disciplined subjects required by capitalism work ultimately through the body. He shares with ideology theorists the attempt to account for the crucial social paradox of our epoch-that our highly elaborated social system of late capitalism is at once deeply riven with inequalities and conflicts of interest yet still manages to operate smoothly enough to avoid the crises of antagonism that might spark revolution. He differs from them in disarticulating power and its attendant disciplinary mechanisms from a direct correlation with the class system, and in focusing less upon the forces that produce subjects in ideology, than upon the micro-technologies of power which produce, organize, and control social differences.

Does the smartphone free us or control us? Does it reproduce and reinforce hierarchies and biases, or does it allow for counter-narratives?

Cinema

Let’s rewind a little and look at the way Wes Craven continued to use the phone for horror while it was changing. This famous opening scene from Scream (1996) depicts Drew Barrymore in a cameo as the unassuming babysitter murder victim. The cordless phone allows her to walk around the house, letting the tension build.

Scream reminded us all that we could be seen even when we could only hear the caller on the other end. Although the first cell phone was invented in 1973, they were just starting to become more ubiquitous (there was even a smartphone by 1994; who knew?). The cell phone allowed the killer a kind of surveillance and haunting that was previously unavailable. Lucky for me, it was also around the time that I was doing a lot of babysitting in a suburban town. I still earned just $4 an hour after thinking I would be gutted every time the unfamiliar house-phone rang.

A year prior, Clueless (Amy Heckerling, 1995) gave us cell phones of status, used ridiculously in the high school halls. Well, it seemed ridiculous at the time, but who hasn’t now done something along the lines of calling a family member in the basement while you are sat in front of the TV? In Clueless, the phones highlight the performed nature of the dialogues between Cher and her friends. Even on the film poster, the three main girls pose as if speaking on their phones, so that they become a part of their fashion statements. Of course the phones date themselves quickly, adding to the chronotopic quality of the film in 1990s Beverly Hills, which is both representative of America (as seen by the outside at least) and drastically not (for most Americans).

In Mean Girls (Mark Waters & Tina Fey, 2004), the phones are landlines but the newish use of putting people on hold and allowing multiple callers is utilized in an epic split screen four-way phone call. Dramatic irony (of those on screen but not on the call), embarrassing mistakes (talking to the wrong person), listening in, and sharing secrets make the phone a fantastic comic device and symbol of our performative natures. (This film is also an amazing adaptation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, but I digress…no phones in colonial Massachusetts.)

I was reminded of the Mean Girls split screen scene with a similar setup in the finale of Derry Girls, a television show about a group of teens growing up in Derry in the late 90s. Irish politics and terror is always in the background (a little like Belfast, a film that I also loved). Erin and Michelle, two of the main characters, are not speaking over a disagreement about Michelle’s older brother, in prison for murder. Because of this and a recent plot twist placing one of the group members in a different town, we see a comical phone scene. Unfortunately, I can’t find the clip online, but the whole series is worth a watch and the scene loses a lot without the buildup. With call waiting mistakes on a hamburger phone and the cousin-friend downstairs picking up the phone incognito, we have a typical late 90s comedic phone situation, that could probably only happen in the late 90s. So, the scene as one of historical fiction, uses the chronotopic details well.

For a viewer like me, about the same birth year as the Derry Girls would have been (and the writer of the show, Lisa McGee, who wrote a semi-autobiographical script and was born in 1980 just like me), it puts us right back to that time of our lives. It makes us at once the same –school dances, exams, conflicts with parents or friends, fun roaming the streets and doing not much at all—and then aware of our stark differences when they show an NRA bomb go off or the encounters with ubiquitous military and police.

Both of these scenes might help us reflect on the way we speak to others. Would we say something again if we knew a particular person were listening? How do we attempt to manipulate friendships or other relationships for ourselves? In the absence of phone calls post-smartphone, have we avoided mishaps like the above or have we regressed to a quieter, brooding manipulation? Or one that takes place on social media, even less ‘face to face’ than a phone call?

Also before smartphones, as part of normal life at least, was The Wire (2002-2008). You may remember cell phones from this great Baltimore-based detective show: payphones and burners, police phones and walkie-talkies. They featured everywhere. Here’s a scene where Lester prank calls marlo (also disguising his voice) and another scene of disguising a voice on the phone by Proposition Joe.

Can you sing about a text?

Search lyrics for texting – and you’ll find most of it about ‘drunk texting’ or generally texting to being caught texting the wrong person (usually cheating) rather than the conversation itself.

Example: Chris Brown “Drunk Texting” (2018): “Just can’t stop myself so baby, I’ll be blowing up your line. I got you on my mind. …I’ll be drunk texting you…” Texting facilitates the sharing of drunk feelings. I think this is a relatable idea, if rather simple.

Then there’s “Why you texting?” by Michael J Woodward (2021) and “Text me” by R. Kelly (whose soft R&B voice just sounds creepy now). Ariana Grande’s “Thank u, next” implies a text in the title as a quick way of ending something not serving you. The video features an initial high school hallway mise-en-scene with rumours circulating due to online messages as well as a couple phones and even an old school mix tape.

Others, like Lady Gaga, go retro:

And Adele doesn’t include the actual phone in her video for “Hello” but she says the other “doesn’t seem to be home.” The old phone seems a more poetic device to discuss heartbreak. There is something romantic about the phone call and even musical in itself (whose mind doesn’t go to Stevie Wonder whenever somebody says, “I just called…”?).

I’m deathly afraid of singing in public and refuse to do karaoke nights even after a few drinks and even after living in Hong Kong for eight years. However, I think I could sing on a phone. Not that I really have a reason to, but I would do it. What does that mean? Do we hide behind our phones? Are we more confident? Do we not care?

Will we keep singing about phone calls even if we barely use them? How will the phone become purely nostalgic? Will we ever lose that ‘old phone ring’ many keep using on their smart phones?

We can easily capture any sounds we hear with our phones whether a call or not. The line between live call and recording can be blurred, since many send recorded voice or video and photos to friends in lieu of live conversations. We don’t want to interrupt people’s lives, and sometimes time zones stand in the way, but we can capture a moment for them in this way.

Nigerian artist Emeka Ogboh has been experimenting with “soundscapes” for many years. He first had the idea that the sounds of his hometown could be art when a friend guessed that he was in Lagos upon hearing the background noise during a phone call.

The ease of sharing sounds, whether professional music tracks, our own playing of an instrument, or the sounds of city life, is made possible with cell phones and smartphones. We receive layers of texts through the background noises of the calls we make out in public squares or within the birds’ music of the forests.

Texting is a text; can it be part of a novel?

There are many novels with embedded texts, some awkwardly, others more poetically and connected to characterization. Two novels that do it well are Super Sad True Love Story (Gary Shteyngart, 2010) and Beautiful World, Where are You? (Sally Rooney, 2021). Shteynhart uses phone messaging as one of the embedded texts to flush out the relationship of the main characters; as the New York Times says:

As recounted in Lenny and Eunice’s own slangy diaries and their e-mail and text messages, their relationship is like a country song a ballad of longing turning into love turning into loss.

The novel is also part commentary on an imagined dystopian New York, complete with smartphone obsessions. As NPR puts it: “Americans now spend all their free time shopping and watching videos on their ''apparats,'' smart phone-like devices that nobody is ever without.”

The latter novel, from a much later date, includes a few smartphone references in the background (dating app, shared video) but mainly utilizes the text by means of communication (other than in person). We see different parts of the characters through the language they choose as well as the through the thoughts going into whether or not one should text and exactly what/how, such as this passage on p. 144:

Simon: Do you want to come over here?

…

A few seconds passed. He rubbed his jaw with his hand, watching the screen, which reflected on its surface the bulb of the ceiling light in its glass shade overhead.

Eileen: !!

Eileen: I was not fishing for an invite!!

Simon: I know that

Eileen: are you sure?

Simon: Yes

The grammatical formality of Simon and informality of Eileen (a writer and editor) emphasize their personalities and the confusions in their romantic relationship. Something similar can be seen between the other two in a relationship, Felix and Alice, on pp. 218-9. Ultimately, the texts enable meeting points but also conflate uncertainties and misunderstandings while the climactic moments are decidedly without phones. Additionally, much longer emails (several pages each) between the two female friends create an antithesis of clear and healthy communication to that of the lovers.

Because texts are usually intermittent, their unusual flow doesn’t fit smoothly into a storyline. Perhaps they are closer to epistolary examples in literature, as they are written forms of communication, but they nature of their potential immediacy also changes their effect drastically to be something between a call and a letter (or email) and something perhaps entirely itself. A topic for another day.

Can literature capture the humanity in a text? Or is a text lacking of humanity by nature?

“Cell Phone Novel” is a piece of fiction published by Justin Wolfe in Columbia (2013) that talks about a romantic relationship as filtered and affected by cell phone use. The fact that is five pages long but called a novel perhaps emphasizes the fleetingness of interaction emphasized in the story. This is how the pair meet:

The way we got together in the first place was that I texted her one night about how I was going to kill myself because nobody wanted to go to a bar with me; I was trying to be funny but she didn't get that tone from the text, not totally, and then my phone was ringing because she had called me and her voice was saying "Hi" on the other end. Before that we had never talked on the phone, though we had texted each other a hundred times, maybe two. The next afternoon, we went to the mall and I helped her pick out a green silk tie for her father's birthday. (p 115)

The story moves between short texts and prose inner monologue narrative that conjectures about the use and impact of various punctuation, how to ‘laugh’ through texting, and text prediction that ultimately wants to write ‘I love you’ instead of ‘I can’t talk.’ There is an ongoing critique of the lack of tone, and therefore reality, on the phone. Overall, the feeling is isolation, which I’m sure many of us have felt whilst alone with a phone (but a plethora of contacts at the text-ready).

Changing what already exists

There is something about adding contemporary phones to something old that shows the ridiculousness of our usage. Korean artist Kim Dong-kyu adds smartphones to famous works of art:

The universal malady struck a chord with South Korean designer Kim Dong-kyu, who tells Quartz that he was deeply bothered by how much people obsessed over their phones—often to the point of missing out on real-world experiences. “Smartphones emphasize connection and communication,” Dong-kyu muses.”But in reality, it seems that only severance [alienation] and superficiality remain.”

The phones in his art seem to take away artistic solitude in the works or become weaponized in other cases. The link above depicts several of his images.

Similarly, digital artist Gerry Buxton puts an iPhone in a caller’s hand, who says: “Oh Jeff... I love you too... but...” a response to Lichtenstein’s work that we looked at last week. Perhaps it shows that some things stay the same. The depiction is of a woman in a head scarf instead of a blond bombshell-type; maybe it suggests that new phones can also empower.

Ephemeral texts

What about Tik Tok or Stories (on Instagram or Facebook) – dialogues that disappear? How might this change a narrative?

Dating apps and their messages? I’ve tried doing this in a novel and mostly avoided the actual communication in the dating app other than to discuss how frustrating and game-like it can be. Nobody wants to read the torture of waiting this way.

The ubiquitousness of various modes of video calls is fairly recent. I wonder if they will enter our literary dialogue? After all, they can catch you off guard in more ways than one. How many time have we called Grandma with her curlers in or exposed uncle XX still in bed at ten on a (remote) work day? How many clues to a mystery could we capture in the background of video call?

And then, what about the idea that with a smartphone we are all creating many types of texts all the time? Some more permanent, some ephemeral? Some that reach wide areas of the globe instantaneously…

Photos…social media content…written or verbal texts…

Are these really phones anymore anyway? They have gone beyond…hors-category?

Do we need to turn photos into artwork, like the artists Duo, or are they art already?

Can smartphones “activate gallery space” or do they take away from the experience, do smartphones keep us from appreciating art?

Further reading short takes (before my final thoughts)

It’s hard to keep up with something that’s changing so fast. But here are a few who have tracked its impact through or on the arts or on culture (that may be represented in the arts) around the world in the last decade. Many of the questions and changes to the way we access information or artistry will remain relevant for a long time.

Ageing withrtphones in Ireland: When life becomes craft (Pauline Garvey and Daniel Miller, 2021) investigates the effect of smartphones on the aging process, and hypothesizes that it allows people to feel more youthful. It asks questions such as: “[D]oes the smartphone simply lose its associations with youth or has its incorporation made older people in some sense more youthful?” (chapter 5)

“In Defense of African Film Studies” (Boukary Sawadogo, Black Camera, 2021, pp. 399-404) discusses the aid of smartphones in distribution (within and exterior to Africa).

“Emergency Cinema and the Dignified Image: Cell phone activism and filmmaking in Syria” (Chad Elias, Film Quarterly, 2017, pp. 18-31) begins by discussing the newness of the “use of the cell phone camera as a tool of documentation, political activism, and creative expression” during the uprisings beginning in 2011. Although we are talking a lot about this documentation of the Ukraine war now, in terms of live video as well and more sophisticated methods of capturing (as well as the possibility of doctored videos), even the ability to quickly send a photograph a decade ago impacted not only this uprising but others around the world. The journal also discusses aspects like uncertainty in images, documenting grieving, questions of creating narratives vs montage, and the cinematic imagination:

By editing these disparate pieces of footage, and adding his own voice to the audiotrack, [filmmaker Ossama] Mohammed develops a cinematic essay on the Syrian uprisings as both “a revolution by images and a revolution of images.” This distinction suggests that the images captured by citizens on their cell phones do more than simply communicate a message. Rather, their political potential lies in the liberation of a cinematic imagination that had been stifled under a system of state-managed cultural production.

“The Magic Inside Your Cell Phone and Its Broad Societal Impact” (Irwin Marc Jacobs, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 2017, pp. 138-154) has a lot of technical information about the development of cell phones, but also investigates social impact, such as the positive effect on students who have access to homework help 24/7. The inclusion of this in a philosophical conference and journal implicitly ask us to consider the way developments especially in smartphone sensors (heavily discussed here) affect us as humans.

“Global Penetration of Korea’s Smartphones in the Social Media Era” (Jin Dal Yong, Chapter 8 in New Korean Wave: Transnational Cultural Power in the Age of Social Media, 2016, pp. 151-168):

Digitization, which refers to the combination of digital technologies, their techniques and practices, their uses, and the affordances they provide, has been a key feature of the latter stages of Korea’s compressed modernity…

“Miniature Pleasures: On Watching Films on an iPhone” (Martine Beugnet, Chapter 11 in Cinematicity in Media History, 2013, pp. 196-210):

With its diminutive screen and set of earphones, the smartphone as screening device encourages the kind of individual and intimate viewing that appears, on the one hand, typical of spectatorial habits in the age of the digital and, on the other, more evocative of the kinetoscope’s peephole apparatus than of the film theatre.

Final thoughts

Finally, an article of post-theory: A theory of a theory of a smartphone. Are we trying to figure out smartphones when really they are just tools we can use for evil or good, for truth or lies, depending on whose hand they are held in?

Will we continue to use the old school phone for nostalgia? Will writers shy away from including contemporary phones in their texts for fear of dating the literature too much?

What other texts use a phone call, or perhaps a smartphone, as defining feature or repeated trope? How do they change the reading of the text?

So what? Who cares? Is the phone motif merely a marker of time and a tool of communication? Is it a simple reflection of society? Or, is the phone a unique symbol? Can it help us to think about the way we communicate? Does it provide a threshold for understanding?

Is it about trust and secrecy? About our sometimes manipulative and selfish natures?

Is every phone call a text? A performance? Does holding something in our hands signify a prop device to our brain, a method of playing with reality?

My line of thought today feels rather like a session on my smartphone. Here and there, lost a little along the way. It’s hard to keep a linear type of reasoning about something that keeps changing so quickly and has a different purpose and reality for each of us. For me, overall, the gift of access, creative functions, and extension of representation outweigh the negatives. Somehow if we can focus on the positives - since they’re not going anywhere - maybe they, too, can become a beautiful trope in our artistic histories. But artists would also do well to continue to convey the harm they can do by taking away our natural realities.

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

I found this deep dive into mobile phones and their meanings fascinating, and you've covered here many things I hadn't considered, particularly around the use of them within novels and films. I was reading a book recently and found myself thinking "why hasn't the main character used her phone for that, it seems unrealistic..." then I realised it was set in the early 90's! I hadn't read the blurb closely...so it did make me think that the use of technology within a piece of art can easily date it. I am in a constant quandary of loving/hating my smartphone (as I think many people are). I loved being able to message with my oldest child when they went to University, for example, but constantly worry about my 15 year old seemingly having a mobile gadget in their hands at all times. As an aside, your comment at the beginning about 'I put a lot of limits on my phone use, but this isn’t a mindfulness or productivity post about how I get my writing done...' - this would be something I would love to hear more about in a possible 'how I get my writing done' post!! : )