In a tweak of the Tuesday Topics section of The Matterhorn, I’ll be sticking with the topic of Paul Auster for a few weeks, including a look at his work on films, his use of critical theory, and his non-fiction books.

I also recently recorded an earlier article for my new podcast that discusses one of Auster’s early works (link on the text connects to Podbean, Apple, Amazon, and other listening platforms):

In case you missed it, in this same format last month we looked at Jazz:

Jazz in the arts (now free)

Jazz, identity & the meaning of life (now free)

Jazz conversations (Jeffrey Leonard & Ken Ross)

And this weekend, I tried something a bit different by offering a space for conversation about the topic of engaging with “the other side.” The provocation was met with some really fascinating responses as well as further recommendations of newsletters, podcasts, articles, and biographies. Thanks so much for all who participated! The thread is still open for response.

Paul Auster (introduction)

Every week, The New York Times Book Review asks an author:

“You’re organizing a literary dinner party. Which three writers, dead or alive, do you invite?”

Well, I’m still waiting for the invitation to interview with the NYT, but I’ve already got an answer to the question: [two selections of many authors I’m constantly considering each week I read the column] and Paul Auster.

Although I had already long loved a variety of literature, in part thanks to some great teachers, Paul Auster made me want to be a writer. He was the first contemporary writer that both wowed me and didn’t seem to take himself too seriously. His books contain many layers of meaning, and yet, his stories are also of everyday experiences. Though they may play with imaginative ideas and forms, somehow they always stay grounded. They always seem to have very practical messages you might imagine discussing while at a baseball game (a common metaphor used by Auster, who is a huge fan of the Mets).

But I think the simple humanity of his ideas and careful look at the culture of the everyday are not simple at all; they are the essence of life. He captures the ideas so beautifully through story, image, and a literary discourse that runs deep.

When you meet someone else who loves Paul Auster, you both kind of light up. Don’t you? There’s a joy that someone else has also discovered him. It’s as if you share a secret language.

Being Paul Auster

And language is something that interests Auster greatly. It doesn’t mean he uses flowery words. Instead, there is something both natural and precise in the way he writes prose. It’s too consistent to just be down to a good editor or perhaps collaboration with his writer-wife Siri Hustvedt.

Auster got his start in publishing through translation (French to English) while living in France. Although in interviews, he often claims that he does not infuse his novels with elements from French poststructuralists, many including myself have noted how strong the influence seems to be. I sometimes wonder if simply reading other French novelists and immersing himself in the culture made him arrive at some of the same ideas as Derrida without purposefully studying his work.

Relatedly, here’s a conversation he had with a Japanese translator on “cross-cultural communication.” There’s also an interesting interview with the author in this French journal, TransAtlantica, that partially discusses the act of translation. They discuss his work as a constant form of translation, including this section:

Nathalie Cochoy: In “White Spaces,” such an important text, you seem to constantly translate sentences into other versions of themselves. Meaning is never fixed but open to infinite possibilities… You then succeed in speaking about silence, not so much by describing the movements of the dancers as by turning your text into a dance of words…

Auster: I wanted to write about nothing. I wanted words just to be words, but I wanted those words to accompany a dance. Somebody in France is trying to do it, to make a show of it. I don’t know if he’s getting anywhere, I’m not sure, but there’s something under way. I hope it happens.

Maybe because of this influence, the Brooklyn-based writer is considered “super cool” in Europe.

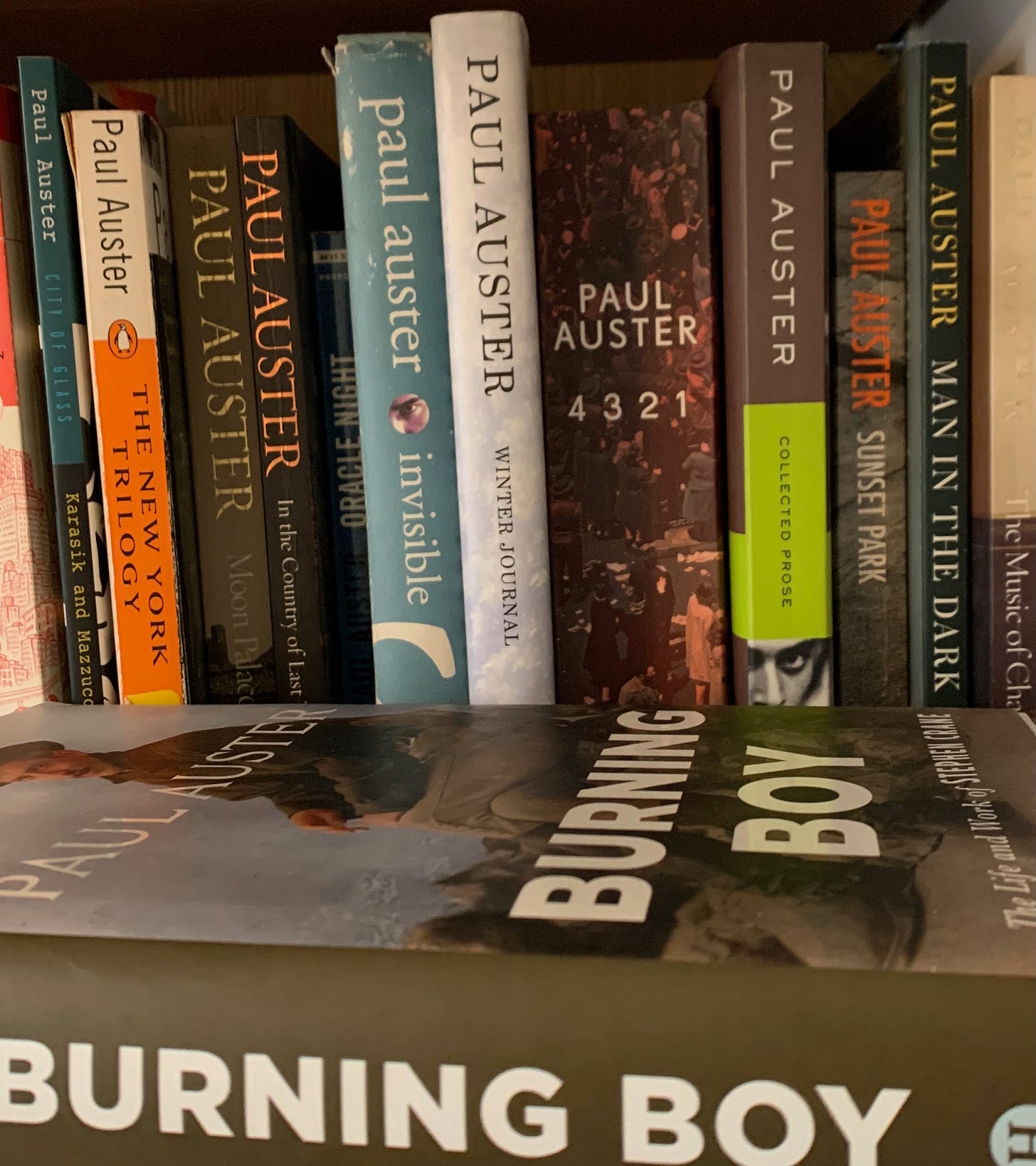

After some time writing several plays and working as a teacher and professor, Auster eventually found fame in the 1980s through The New York Trilogy, a series of detective stories. Although the stories are much more than that. They are like labyrinths of philosophy through the streets of New York. That fame gave him freedom to keep writing prolifically for decades, and he’s still doing it at the age of 75. In 2017, he published the acclaimed tome 4 3 2 1 and since then, he’s published four non-fiction books that I’ll get into in a couple of weeks here.

Becoming a writer

Below, Auster talks from his Brooklyn home about what got him into writing. This is a short but fabulous interview! I highly recommend watching it if you are a fan of Auster (before or after these posts) or if you are a writer.

Here he discusses the way baseball player Willie Mays had inspired him when he was only seven to write. Auster had an encounter with the great player but had no pencil with which to get an autograph. “After that day, I always made sure to keep a pencil in my pocket. And I tell my children to this day, that this is how I became a writer.” If you listen to the talk until the end, you’ll hear how Auster finally gets his autograph…fifty-two years later.

He also talks about “aborting novels” and writing thousands of pages in his twenties that he threw out. However, it’s interesting to hear him talk about the way this became his novels later on. The work he built on then gave him the knowledge and wisdom to write later on.

It also gave him the maturity to choose to write only a page or three a day, to make the writing look “so smooth that it is like a piece of music.” Auster is also somewhat famous for continuing to write on a typewriter, and even wrote a book about it.

[Related to our look at jazz writing last week, Auster discusses moving around his home to find music and rhythms that become language in his writing.]

Encounters

In college, I first read The New York Trilogy in a course on contemporary American literature, which we then used again in a course with the same professor on literary and cultural theory. I guess I simultaneously developed a passion for critical theory and the Auster-oeuvre, so the two for me are interconnected.

Since then, I’ve gone on to read most of his works. Some of my favorites are Music of Chance, which takes a lot of inspiration from Samuel Beckett whom Auster met in Paris, 4 3 2 1, for its play with parallel universes and emotional storytelling, and the gorgeous novel Moon Palace:

“I had jumped off the edge, and then, at the very last moment, something reached out and caught me in midair. That something is what I define as love. It is the one thing that can stop a man from falling, powerful enough to negate the laws of gravity.”

- Paul Auster, Moon Palace

As a teacher, I brought City of Glass (part of the Trilogies) to many high school students and also utilized the graphic novel, an adaptation by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli. Using these texts brought up interesting discussions of trauma’s impact on an individual as well as the detective genre, metafiction, place/spatial theory, semiotics, the graphic novel text type, and adaptation. Below, the three authors discuss the process of adaptation at Comic Arts Brooklyn Festival.

[There’s a whole theorizing discourse on adaptation, although often focusing on book—>film; check out: “On the Art of Adaptation,” “Rematerializing Adaptation Theory,” and “A Dialogue on Adaptation.”]

Last November, we looked at the motif of the Phone Call in this text. Recently, I did a voiceover version of that article on my new podcast:

I find myself always coming back to Auster, as a reader, writer, teacher, lecturer…he always seems to enter the dialogue of what I’m trying to say, helping me express it or inspiring to move into new directions. As such, I’ve published several articles about his work:

discussing The New York Trilogy in “6 Thrillers for Lovers of Literary Fiction”

discussing 4 3 2 1 and Burning Boy in “The Joy of the Tome”

“Mise-en-abyme in Wayne Wang's New York and Hong Kong Films” (some of these films were collaborations with Auster; I’ll talk about these in two weeks)

In the news

Even if you’re not familiar with Auster’s novels, you may have seen him in the news this past year or so for one of three reasons: talking about gun violence in America, experiencing tragedy in his family, and discussing his recent tome written during the pandemic — Burning Boy.

Most recently, Auster has spoken out about his views on guns from a very personal place. He’s not politically shy, having started the Writers for Democratic Action group, initially created “against Trump.”

Within a span of days this January following several mass shootings that started the year in America, Auster published several articles on the topic that also relate to his new book Bloodbath Nation, a collaboration with his photographer-son-in-law that depicts the places of American mass shootings in an effort to curb gun violence.

In LitHub, Auster published: “Why Is America the Most Violent Country in the Western World?” where he starts by describing his time in the Merchant Marines. He tells a personal story of a fellow Marine to firstly explain his own horror at the shooting of Martin Luther King, then to expose the stupidity with which some people use guns:

We were standing on the deck one afternoon watching a flock of gulls circling above the ship when Lamar told me about another one of the fun things he liked to do on Saturday nights in Baton Rouge when he was feeling bored, which was to take his rifle and a pocketful of ammunition, park himself on an overpass of the interstate highway, and shoot at cars. He smiled at the memory of it as I tried to absorb what he was telling me. Shooting at cars, I said at last, you must be pulling my leg. Not at all, he answered, he really did it, and when I asked if he aimed at the drivers or the passengers or the gas tanks or the tires, he vaguely answered that he shot in the general direction of all of them. And what if he hit and killed someone, I asked, what would he do then? Another one of Lamar’s shrugs, followed by a laconic, indifferent, almost blank “Who knows?”

In The Guardian, there were simultaneous publications of an excerpt from the new book and an interview with Auster. In the interview, Auster explains the effect of his son-in-laws photographs:

What do you think makes Spencer’s photographs so eloquent?

I think the absence of human figures is striking and the way that there are no guns, no reference to mass shootings, just these often rather ugly buildings in the middle of rather nondescript, depressing American landscapes. There’s an emptiness to them. I don’t want to get too pompous about it but I think that emptiness does reflect the emptiness of this world we’ve created in which people are slaughtered with so little effect on the life of the country. We all get upset, we all complain, and yet things stay the same. And the gun lobby remains very, very strong.

Art can truly tell a story and influence people’s opinions on a deep level. I hope that his work makes an impact on at least some individuals currently fighting for the ‘freedom’ to own and wield a gun in America.

In the excerpt from the book, Auster also talks about a secret personal tragedy in his family: his grandmother had killed his grandfather with a gun. The insinuation that the gun makes it easier to kill, faster and less personal.

Auster has seen personal tragedy in a different way recently with the deaths of both his son and grandchild. After many articles sensationalizing the stories, The New York Times tried to put something together that made the story more nuanced and humane about the perils of addiction. The article attempts to show that although addiction may have consumed the family, there was still love before tragedy:

The young family moved into a small apartment in Park Slope, not far from Paul Auster’s brownstone. Daniel read bedtime stories to his daughter and took her for strolls around the neighborhood. In a photo taken for her first Halloween, the family is dressed up as characters from “The Wizard of Oz” — Daniel as the Tin Man, Zuzan as Dorothy and Ruby as the Cowardly Lion. Later that fall, neighbors noticed a jumble of toys and baby clothes on the Bergen Street sidewalk.

Despite, and perhaps because of, this sadness, Auster continues to write. During the pandemic, he wrote a book on Stephen Crane. Originally slated to be a ‘short’ biography, the writing took on a life of its own, as he describes in this interview with The Guardian:

That was my plan: 150 or 200 pages. Then one thing led to another and it turned into this new member of the Rocky Mountain chain. It’s an enormous book, I know. For a life that was that short, it’s pretty strange that I should have written so much. But it’s not just a biography, it’s also a reading of his work: it’s about evenly split between the two.

The book is beautifully written; despite its length of nearly 800 pages, each sentence is exquisite. Like the biographies of Hermione Lee, this work is much more than a biography and inspires to go back to Crane to read him more carefully. What do you think about Crane’s work?

Besides the Crane biography and the book of photography, Auster has recently published Talking to Strangers: Selected Essays, Prefaces, and Other Writings, 1967-2017, Groundwork: Autobiographical Writings, 1979–2012, and A Life in Words: Conversations with I. B. Siegumfeldt (of course, with a typewriter on the cover).

These are beautiful works of non-fiction. Auster has so much wisdom to share with the world.

But at the same time, I’m dying for that next novel to come out. No doubt it will both comfort his readers with that sage voice and simultaneously shock us with new ideas and unanticipated experiments.

Do you read Auster? What are your favorite books? What has he taught you about the world or made you consider in a different way?

Continue the series:

I loved The New York Trilogy and have been wanting to follow up with more of his works for a while. This resparks that initiative. Also glad to learn more about him and his perspective.

Love this - it really makes me want to check out Paul Auster. My only interaction with Auster has been the Jim Jarmusch films (with a film-major daughter in town from school in NYC, I'm thinking we need to screen Blue in the Face). And, I should read the guy, perhaps starting with the New York trilogy! But, this also reminded me how much I love the stories of Siri Hustvedt who was married to him - so likely I'll go and check out a couple of her books I haven't read as well! Thank you as always for the inspiration. 🌷