Jazz in the Arts

Where else do we find jazz's influence & how does it become a concept more than a musical genre?

Jazz is not just music and dance. We see it, hear it, feel it in many places and other types of artists use it for inspiration. I’ll go on to talk about jazz in movement when we look at jazz in your own writing. Today, let’s take a look at film, visual art, and literary works.

First, I’ve got a brief overview of jazz’s origins and some resources you can take a look at in order to orient us. [You can also read last week’s introduction to this topic (free post).]

The Harlem Renaissance & The Jazz Age

First, just a little bit more background to help us think about the question of jazz and identity a little further along.

Although jazz began in the nineteenth century, as noted above, it came to fame and a greater part of American (and European) culture during the Harlem Renaissance. It was such a strong influence that the 1920s was even called the Jazz Age. However, jazz of course didn’t end with the 1929 stock market crash. The ‘age’ was connected to excess and to the time between world wars when America was blossoming.

Artists like Louis Armstrong (below), Ma Rainey, Duke Ellington, and Fats Waller (sadly, no relation to yours truly) recreated what jazz was and expanded its musical language.

Jazz was an integral element of the Harlem Renaissance. In many ways, it created a space to be heard and validated a Black American identity in an elevated way: the definition is, of course, greatly nuanced and continuously changing, just like jazz. It is at once individual and creative but also part of a human experience and coming from a rich cultural history.

The Harlem Renaissance was about giving a voice to the experiences of African Americans, and nothing gave expression to the African American experience better than jazz.

1. Jazz was born out of the Black experience in America, basically fusing African and European musical traditions.

2. Jazz evolved from slave work songs, spirituals (religious Black American folk songs), blues, brass band music, and ragtime.

3. Jazz, more than any other music, has been intimately linked with legal and social equality for all, particularly African Americans.

The above link also has a great lesson plan for grade 5 students. Below is a nice overview that could be used to start the lesson. Most teachers also know about Crash Course (started by author John Greene and his brother). But these videos are also great for anybody, not just students. The information is well researched and clearly presented.

The Harlem Renaissance established itself as a period of great innovation within jazz. There was a development with the piano making it more accessible for Black musicians. Innovations like this eventually because characteristic of the artists, and the music, of this period.

There were many prevalent themes in the works coming from the Renaissance. These included ideas of a “New Negro,” a person who could fight racism and stereotypes through literature, art, and music. These themes relied on the influence of slavery and the effect it had on the Black identity.

Further reading and discovery:

Black History in Two Minutes or So’s intro to the Harlem Renaissance (another great youtube.com channel)

“The Harlem Renaissance as Postcolonial Phenomenon” (Robert Philipson, African American Review)

“Symbols of the Jazz Age: The New Negro and Harlem Discovered” (Gilbert Osofsky, American Quarterly)

“Jazz As Part Of The African American Cultural Diaspora” (James R. Gore, Art Beat Blog)

Film

There have been many films about famous jazz musicians and the recent film Soul (2020), featuring Jon Batiste’s music, has brought jazz to a new generation. Soul was Pixar’s first depiction of a Black lead character and used a careful investigation of jazz’s roots in Harlem to tell its story. The film also grapples with the desire to create art — the main character is a band teacher who dreams of playing jazz professionally but falls into a manhole at the start of the film, struggling in a purgatory and considering the meaning of life (we’ll come back to jazz & the meaning of a life next week).

Although Batiste has a large range of composition and performance, his love for jazz is evident in performances like this one and in his position as the Creative Director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, which I have not yet had the pleasure to visit. If you’re a teacher, note that they have virtual tours for students as well as workshops for all ages (pre-K through to university).

In a discussion of his music as a method of political voice movement in The Guardian especially for BLM, Batiste talks of his love for jazz in relation to his culture:

“I see jazz as a superpower,” he says. “It has never depended on popularity to maintain relevance because its value is undeniable; it represents all the nuances of the human soul. It is an honour to play this music because it is my heritage – it is the Blackest, deepest American classical music that has grown to become a universal art form. Jazz shows you that something can be from a specific experience and it can be adapted in a way that’s not appropriated.”

Painting

Romare Bearden was an incredible muralist that followed from the Harlem Renaissance, working in Harlem in the decades just after. His work often included depictions of jazz (and blues) music being played or danced to. You can read Ralph Ellison’s take on his work in “The Art of Romare Bearden,” which likens him to a Picasso figure speaking for an African American identity, but also to the notion of a freedom of racial identities:

Thus in the poetic sense these works give plastic expression to a vision in which the socially grotesque conceals a tragic beauty, and they embody Bearden's interrogation of the empirical values of a society which mocks its own ideals through a blindness induced by its myth of race.

Bearden seems to be connected to the fabric of artists everywhere at his time. In a fascinating discussion among James Baldwin, Alvin Ailey, Albert Murray, and the muralist (“To Hear Another Language”), he talks of ‘living with’ Langston Hughes and other artists in Harlem as well as encountering Matisse and Picasso in Paris.

And Matisse did have his own fascination with jazz around the same time as this encounter, specifically in the muralistic book called Jazz. As part of his “cut-outs” series, he included dancers and saxophone players, for example. Matisse inspired Bearden, as seen in this famous work called “The Piano Lesson.”

In a time just after the second World War, Matisse’s creation of something new and beautiful out of the pains of society was not unlike the birth of jazz music. The Met Museum describes the book as such:

Henri Matisse's radical rethinking of what an illustrated book could be, depicts scenes of the circus, travels, mythology, and fairy tales. Yet despite the rhythmic juxtapositions of forms, the undulating lines, and the ostensibly joyous subjects, "Jazz" is haunted by a deep sense of danger, loss, dread, and even death.

Many other visual artists have, of course, turned to jazz for inspiration. But a key figure whose work seems born out of jazz is that of Jean-Michel Basquiat. In “How Music Inspired the Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat,” Ted Stansfield tells us:

Jazz was definitely the most important musical genre for Basquiat. His father played a lot of jazz while he was growing up. Very early on, his father described in an interview how Jean-Michel drew on the floor while he played his jazz. Art and music came together very early in [Basquiat’s] world. Through listening to that music, he also developed a profound appreciation for pioneers of bebop, which is a more avant-garde kind of jazz that was really spearheaded by Charlie Parker. He cites Parker repeatedly in his work, he cites Parker’s tragic loss of his daughter at the age of two, and he understood Parker among many other jazz musicians as real champions of Black excellence, and he wanted to celebrate that and his work.

For a thorough investigation of Basquiat’s roots in jazz, check out this article by Evan Haga called: “Basquiat and Jazz: A Guide.” The article includes embedded music by jazz musicians who have in turn been inspired by Basquiat’s art, such as this one by The Vandermark 5:

(There’s also a musical in the works on his life by none other than Jon Batiste.)

So many collaborations and inspirations among art forms makes me consider jazz as truly a philosophy in addition to a form of music. Ultimately, jazz is about freedom and a lack of limits, although it is rooted in particular structures of musical language — rhythms, notes, and historical references. Is its musical articulation the ultimate manifestation of these ideas or is the music the spark of other creative forms?

Poetry

When we think of jazz and poetry, we may consider both references to jazz (and its musicians) as well as a style of using language. Langston Hughes is perhaps at the center of this: one cannot think of his poetry without considering jazz music. He once said:

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.”

Hughes wrote of and through jazz and also performed with jazz musicians:

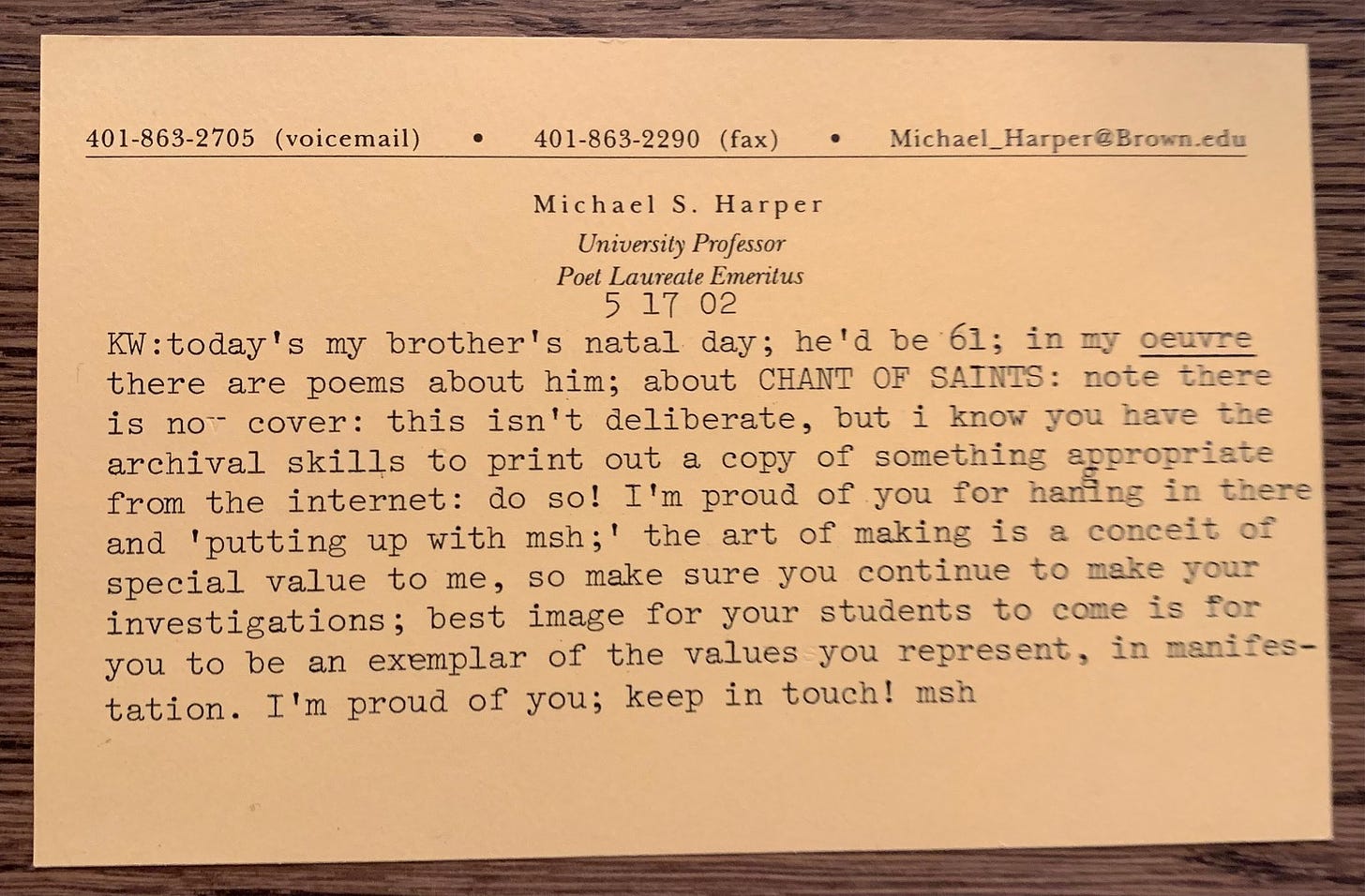

If you are really interested in this topic of jazz in poetry as well as other art forms, please look at the book Chant of Saints edited by poet Michael Harper and Robert Stepto. Here’s a link to a review by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.. The book also contains the above mentioned article from Ralph Ellison on Romare Bearden’s work (p. 158+) and includes color reproductions of his Odyssey murals (Ellison also utilized the epic Greek poem).

Harper’s poetry and essays also feature in the book. I was extremely lucky to take a senior seminar course with Professor Harper during my university days. We met in a small old room on campus, six of us arriving to sit at the round wooden table in the evening for three hours. He drove up to Maine from Rhode Island once a week for the course, armed with a huge pile of books that he may or may not refer to or quote from and ask us to comment, making the connections between ideas ourselves.

Harper gave each of us a copy of the hardcover book as graduation presents with typed index card inscriptions. Below is a photograph of mine. I guess in some ways, this newsletter is my method of “continu[ing] my investigations.”

Harper was deeply interested in the Black American experience and history, but also much more than this. He was influenced by his travels and his many students, he said. As Poetry Foundation articulates: “Harper was distinctive in that he often sought to bridge the traditional separation between black America and white America, writing poems that speak across the divide and draw upon elements of the racial, historical, and personal past of all Americans.” The four poems he selected of his own oeuvre to include in Chant of Saints include domestic travel (Michigan, West Virginia) as well as international (Jamaica, England, South Africa, France, Belgium) as well as references to other artists like the poet Galway Kinnell, Edmund Burke, and Robert Hayden. To emphasize: these references are all included in four poems. His essays include many further allusions to attempt to bring the world a little closer.

Here are a few excerpts from poems included in a book he also edited with Anthony Walton: The Vintage Book of African American Poetry (2000) —

From “Dear John, Dear Coltrane” (p. 267)

Sex fingers toes in the marketplace near your father's church in Hamlet, North Caroline -- witness to this love in this calm fallow of these minds, there is no substitute for pain: genitals gone or going, seed burned out, you tuck the roots in the earth, turn back, and move by river through the swamps, singing: a love supreme, a love supreme; what does it all mean?

From “Where Coltrane Is” (p 271)

Dreaming on a train from New York to Philly, you hand out six notes which become an anthem to our memories of you: oak, birch, maple, apple, cocoa, rubber. For this reason Martin is dead; for this reason Malcolm is dead; for this reason Coltrane is dead; in the eyes of my first son are the browns of these men and their music.

Harper died in 2016 after a long remarkable career, leaving us with many poems to consider. One day, I will have to do a whole post on ‘chant of saints’ and Michael Harper. For now, you can ‘meet the poet’ (posthumously) here:

Harper includes many others in his books who utilize jazz like Robert Hayden, Richard Wright, and Gwendolyn Brooks, who famously wrote: ‘We jazz June” in the poem “We Real Cool”; here’s a musical rendition by Prince Harvey:

Novels

A lot of us think of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby as soon as we hear the words The Jazz Age. Here, you can read about what the novel “reveals about the jazz age.” I loved teaching this novel for many reasons; its structures are fascinating and pedagogically useful (frame narration, complicated protagonist/antagonist situation, careful symbolic references) and its dichotomies allow for deep discussion and investigation beyond the surface level plot and connections to history.

Novelist and short story writer Zora Neal Hurston was heavily influenced by jazz music. She penned an essay called “How it Feels to be Colored Me” (1928) about an experience of listening to jazz next to a white man, and the way this made her consider her racial identity and its celebration in music:

A white person is set down in our midst, but the contrast is just as sharp for me. For instance, when I sit in the drafty basement that is The New World Cabaret with a white person, my color comes. We enter chatting about any little nothing that we have in common and are seated by the jazz waiters. In the abrupt way that jazz orchestras have, this one plunges into a number. It loses no time in circumlocutions, but gets right down to business. It constricts the thorax and splits the heart with its tempo and narcotic harmonies. This orchestra grows rambunctious, rears on its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending it, clawing it until it breaks through to the jungle beyond. I follow those heathen--follow them exultingly. I dance wildly inside myself; I yell within, I whoop; I shake my assegai above my head, I hurl it true to the mark yeeeeooww! I am in the jungle and living in the jungle way. My face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue. My pulse is throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something--give pain, give death to what, I do not know. But the piece ends. The men of the orchestra wipe their lips and rest their fingers. I creep back slowly to the veneer we call civilization with the last tone and find the white friend sitting motionless in his seat, smoking calmly.

"Good music they have here," he remarks, drumming the table with his fingertips.

Music. The great blobs of purple and red emotion have not touched him. He has only heard what I felt. He is far away and I see him but dimly across the ocean and the continent that have fallen between us. He is so pale with his whiteness then and I am so colored.

Invisible Man author Ralph Ellison, already mentioned in reference to Romare Bearden, was a musician himself. Much has been made of his most famous novel’s seeming roots in jazz music, not so much through references but in the manner in which it was written. Ellison has said: “I would have to improvise upon my materials in the manner of a jazz musician putting a musical theme through a wild star-burst of metamorphosis.”

Additionally, this article discusses both Ellison’s desire for musical education in America and the inherent dichotomies in jazz. However, Ellison has also critiqued ‘modern jazz’ for its shifts toward a more academic and eurocentric articulation. The New Yorker quotes him:

For Ellison, modern jazz musicians made the mistake of seeking “status and respectability,” and of seeking it as intellectuals and from intellectuals, predominantly white ones. Ellison blames these white writers for their inescapable evaluation of jazz and its specifically black American traditions in terms of their own Eurocentric tradition. For Ellison, the essence of jazz is a specific “reality of life and experience”—that of black Americans—“which nourishes the beginning of jazz and which will continue to nourish its future life.”

Perhaps the two forms can coexist, but the danger is in the power of an intellectual jazz in overtaking the more ‘pure’ form of music. It’s often a debate in any form of artistry: does intellectualizing it heighten its power or decrease its authenticity? This is a dichotomy continuously explored in Dr. Victoria Powell’s The Gallery Companion, which I mentioned last week.

What do you think about jazz and identity? Does it have anything to do with your own identity and is this rooted in Black American culture in some way, whether you identify as a Black American or not?

We’ll come back to these questions next week when we look at Jazz, Identity & The Meaning of Life. Thanks for reading The Matterhorn!