Layering Queerness in Fiction

A guest post from Mr. Troy Ford, fiction writer and founder of Qstack

Today, in anticipation of the next half of this season’s podcast on layering fiction, I have a special guest post from

. I started reading Troy’s fiction on last year and was quickly immersed in his voice and experimental styles. His stories are extremely touching with an edge that makes you think deeply. He also publishes occasional essays about writing or his life as an author.Like me, Troy is an ‘American expat,’ a writer and editor from California living on the Gold Coast of Spain about 30 minutes outside of Barcelona in Europe’s answer to Fire Island: Sitges. He’s had a wide array of careers and experiences in the past, ranging from gardener to taxi driver to interior designer, and currently also defines himself as a house husband and dog daddy.

As an admirer of Troy’s work, I was intrigued when he announced a new publication called

that he planned to launch this June. His current serialization — Lamb — ends each week with the following:LGBTQ+ fiction and writers remain a marginalized population in the world at large, and even here on Substack there is a relative paucity of queer content.

If you have a queer bestie, coworker, frenemy, nemesissy, softball team, gym buddy, book group, favorite guncle, Aunt Butch, or adored florist-caterer-handyperson-bartender—please help extend my reach to the wider community by sharing this post directly with someone who will appreciate a queer story.

Troy’s work related to visibility and community both within queer communities and more general connections outward from these spaces is a wonderful way to use his writing voice. I thought also of my students and the way this publication might inspire them in different ways. As such, I asked if he would be willing to do something in written or audio form for Matterhorn readers and was so pleased that he accepted. He came up with a wonderful combination of philosophical discussion and how-to for writers, with quite a few recommended reads or views embedded within.

In fact, Troy has already completed a soft launch of Qstack, with a novel excerpt from

. But come June 1st, the full Qstack Directory of LGBTQ+ Substacks will debut, with guest posts and community projects.In the meantime, you can learn a little today about queerness in fiction and add your ideas in the comments. Thank you, Troy!

Layering Queerness in Fiction

If you’re reading this, and you’re interested in writing characters with diverse sexual identities, congratulations, you’re halfway there already!

Not everyone is called upon to write stories about characters significantly different from their own general demographic, and that’s OK—nobody needs to rush home and start writing a story about a queer character just because they want to be inclusive.

On the other hand, surely you will have already met some queer people in your life, and they have had some effect on you. As writers, we collect experiences—not in an acquisitive, transactional sort of way, but with an attitude of genuine interest in the diversity of people from which we may draw inspiration to create characters that are as alive in their own way as we can make them.

Certainly for many writers, our main characters are often people who are similar to ourselves in some important aspects. So far, most of my own main characters are cis gay white men—I don’t get extra points for writing about a marginalized community that I happen to belong to; but I also don’t lose points because my main characters are not trans or women or people of color, though I have had occasion to include diverse identities in supporting characters.

“Write what you know” is a great beginning, but there’s no telling all the diverse characters you will need to populate your stories in years to come.

Definitions and Terms

But maybe we should start with a definition of who we are. Specifically, we’re talking here about sexual identity rather than gender identity—as a cis man, I’m going to leave discussion of diverse gender identities to people who live that experience.

Here’s a short rundown of the rainbow at hand:

Gay - someone who is sexually attracted to members of the same gender, usually men for men, although sometimes used by women as well.

Lesbian - a woman who is attracted to other women.

Asexual/Ace - not sexually attracted to any gender, but may be open to romantic relationships.

Aromantic/Aro - not romantically attracted to anyone, but may feel or act on sexual attraction.

Demisexual - attracted to people with whom they share a strong emotional connection.

Bisexual - attracted to people from more than one gender identity.

Pansexual - attracted to individuals irrespective of sex, gender, or gender identity.

Queer - an umbrella term intended to include anyone who does not identify as cis/heterosexual/straight.

Polyamory - engaging in multiple romantic and/or sexual relationships with the consent of all people involved.

“How To Write Straight Characters”

For half a moment, I thought about a cheeky take, along the lines of “The Heterosexual Questionnaire” by Martin Rochlin, Ph.D. in 1972, who tried to flip the script by asking questions like:

“What do you think caused your heterosexuality?”

“When and how did you first decide you were a heterosexual?”

“Is it possible your heterosexuality is just a phase you may grow out of?”

My proscriptive story writing version might have gone something like this:

DON’T call them “breeders”—it’s rude, and reduces their humanity to a single unfortunate consequence of their behavior.

DON’T rely on stereotypes—if all your straight male characters are football players marrying their cheerleader sweethearts and having 2.5 kids each, then you are simply checking off a list of “straight” characteristics, not infusing them with realistic personalities.

DO allow straight characters to live to the end of your story—they shouldn’t all die in childbirth or bar fights three chapters in to give us something to feel sorry for them over.

But this is ridiculous, of course, and yet the sort of advice you will find if you Google “How to write queer characters”—which I did, finding tips exactly along those lines—and so perhaps not so very ridiculous after all.

Stereotypes BAD?

Standard advice places stereotypes as the biggest set of things to avoid when writing queer characters (any characters, really) and yet we have plenty of instances when stereotypes were turned on their head to great effect.

As just one example, let us take as our text the hit TV show Modern Family (2009 - 2020), the sitcom portraying an extended family of three couples in various pairings: a May/December and interracial coupling with Jay and Gloria, a heterosexual marriage between Claire and Phil, and gay couple, Mitch and Cam, with their panoply of wisecracking friends.

Mitch and Cam were hilarious in part because they did have some of the stereotypical characteristics associated with gay men, but also other traits which developed into well-rounded portraits of modern gay men attempting to navigate their experience of themselves and each other with kindness and grace.

What worked was how often they unleashed their penchant for drama, glitter, and arch rivalries to the hilt, and then fretted over what people would think—were they acting authentically? Were they judging themselves (and each other) as harshly as society often does?

Portraying effeminacy, or any stereotype, in gay men (I will leave aside “butchness” in lesbians as a similar stereotype with its own set of intricacies) is hurtful when it is weaponized as a means to mock us and undermine our personal power, and to oversimplify our personalities based on behaviors we may not even exhibit.

Incidentally, I would like to acknowledge that even though many gay men are not in the least effeminate, there is also absolutely nothing wrong with being effeminate! Shocking but true!

Homophobia, at its core, is misogynistic sexism turned toward people both gay and straight. So while we may sometimes say “Don’t give stereotypes like effeminacy to your queer characters” we might also recognize that it is often not the characteristic which is wrong, but the process of taking a trait, running it through a sexist lens, and then weaponizing it as a blanket generalization.

The point is: it is possible to write characters who have stereotypical behaviors and mannerisms, and still have it read as a positive and complex portrait, showing needs and motivations, and inspiring a balanced understanding.

One further specific stereotype concerns the wish for happy endings in queer stories. There was a time when queer characters mostly led sad and lonely lives, punctuated only with furtive encounters in dirty movie houses, or luring virginal ingenues into lives of fruitless degradation, and ultimately, suicide. Perhaps it made for titillating reading to midcentury pulp fiction enthusiasts, but the downside, when all the characters that “look like” us look like that, is of course that young people were not able to imagine ways to live which didn’t involve unhappiness.

It was also another tragic consequence of the AIDS crisis that many of the most famous stories emerging in the 80s and 90s, just as the gay civil rights movement began hitting its stride, turned to the depiction of the horrific suffering and injustice of that time.

The cynical side of that period in our history was the exploitation of our devastating losses to further a conservative agenda which attempted to prove an essential “disease” of homosexuality—what was inherently sick made manifest. It was—is, of course—complete nonsense, but nevertheless explains why so many queer people nowadays still wish to highlight and celebrate positive depictions, and wince when someone chooses to write a story with less than glowing themes or outcomes.

With all due respect, I want to urge every writer to feel free to tell the stories they need to tell, whether comedy or tragedy, something in between, or deep in left field—your story doesn’t have to be anything other than what it is. The only question you need to ask yourself is: Have I given my characters a true and authentic humanity within the context of the story? If you can say “yes” than you are doing the work you are called to do.

Character Worksheets

Perhaps the most important thing to remember when writing characters with diverse sexual identities, then, is that they deserve the same degree of development as every other. When we develop as writers, we are aiming for rich, complex characters with whom your readers can identify, whose personalities inform every other aspect of your story—plot, theme, tone, style, to name just a few.

Do you already use character worksheets to build up a picture of your characters based on set questions like appearance, family history, occupation, etc.? There are templates to be found online that can prove helpful to take your characters from cardboard cutouts to living, breathing people your readers will come to love or hate—for all the right reasons.

If you are having trouble developing a character who is not heterosexual, here are just a few of the many questions you might ask to prime the pump:

Are they open about their sexual identity, or do they keep it private or even try to hide it? Why do they take that approach?

What attitudes or stereotypes did they experience as a child, in the place where they grew up, in their family or among friends? Was their experience accepting, or did they face discrimination—and how did they react to it at the time?

How do they approach romantic and sexual relationships now? Are they satisfied in their relationships, or are there challenges?

What kind of community do they find themselves in during the course of the story? Do they feel like they belong, or are they isolated?

Writing a story, in many ways, is a constant exercise in asking questions of your characters, and finding answers which resonate with their personality as they move through the events and scenes which make up your plot.

Sometimes I like to think of it as improv: you have a setup to start a scene or story, but you don’t have a script, just actors on a stage. You tell them how to begin—start at point A, aim at point B—but it’s up to the actors to inhabit the characters they are playing, and the script—your story—emerges as they interpret the idea.

It’s a constant process of iteration between you the writer (director) and your characters (actors) as you test out different ideas and approaches by allowing the emerging personalities to influence the course of the story, and sometimes suggesting new ways it might take a more authentic or interesting turn.

Where To Start

Why not start small, and imagine What If: What if the sister, the cousin, the best friend or boss of the main character were asexual, gay or demisexual?

Go crazy: What if the next door neighbors are a lesbian couple with mad sword skills and an arsenal of kitanas in Your Zombie Apocalypse? How about a straight celebrity couple looking to hoist their rainbow flag with a parade of queer co-conspirators? Perhaps a gay hairdresser whose supernatural ability with scissors sets the world on fire, one fabulous hair day at a time?

Better yet, try googling “queer writing prompts” and spend a little time sketching out an idea, no commitments, just try something on for size. The possibilities truly are endless.

And Reading, Of Course

And then there’s reading—the perennial answer to every question when we start in a place of not knowing. Here are just a few steps in a queer direction, some of which you can watch as well as read:

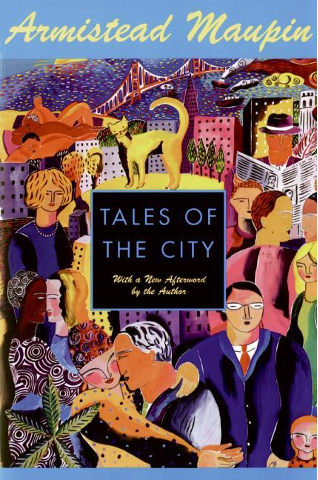

Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City series centers on the interconnected lives of a straight trans woman, a straight woman, a bi woman, a straight man, and a gay man all living out their hopes and heartbreaks in a post-Stonewall era San Francisco.

Several of the plot lines and complications grow out of their various identities, including:

Blackmail over an affair with a trans woman.

Another extramarital and interracial affair which results in a pregnancy.

The death of an extramarital lover.

The unequal economic status of two gay men in a relationship—one of limited means, and one a well-off doctor.

The perception (and assumptions) of racial identity as it intersects a lesbian relationship.

Sexual promiscuity among straight, bi, and gay people.

Although Tales of the City is generally considered more comedy than serious drama, it realistically explores how diverse sexual identities can inform the direction of plot. There are a total of 10 novels, with the recent publication of Mona of the Manor (2024), and four TV miniseries if one were inspired to follow all of the characters through over five decades of an evolving zeitgeist.

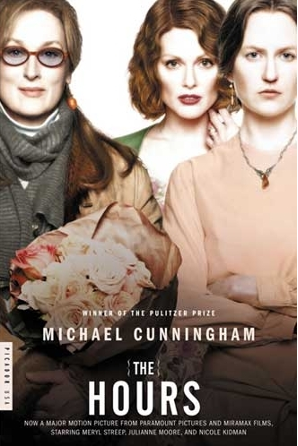

Another book turned into a movie is Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Hours, inspired by the pioneering feminist author Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway. In this fictionalized imagining of a single day in the lives of Virginia Woolf herself in the 1920s, married but closeted woman Laura Brown in midcentury America, and out New York lesbian Clarissa Vaughn at the dawn of the 21st century, the three women face devastating turning points in their respective times.

How about some good old-fashioned non-fiction to open up your understanding of asexual, aromantic and demisexual perspectives? In Eris Young’s Ace Voices: What It Means To Be Asexual, Aromantic, Demi or Grey-Ace chapters look at everything from dating, love and sex to mental health, family, community and joy through interviews with people speaking out on a much misunderstood subject.

If you wanted something a little closer to our Substack home, you might follow some queer Substacks—the Qstack Directory of LGBTQ+ Newsletters debuts on June 1st—and get a little perspective from the rich diversity of voices just a click away.

And finally, give my own serial novel Lamb a look, the story of two gay school friends coming of age in a post-AIDS world, told through reminiscences, journal excerpts, letters, and short stories. We are currently just about a dozen episodes in—plenty of time to catch up and fall in love with the sweet but misunderstood main character. Says one reader: “I am excited and terrified by how much I’ve fallen for dear Lamb.”

Thank you for reading, and many thanks to Kate Waller, a true friend and ally, for the opportunity to share about this complex subject.

Thanks for this thoughtful essay. There is such glorious diversity in the world. Why not celebrate that in our stories?

I'm so happy to see this post and even happier to see it cross-posted here on Kate's stack. As you might imagine, Troy, I've thought a lot about this subject and done a fair amount of hand-wringing about whether I've done an adequate job of fully realizing the LGBTQ+ characters in "The Memory of My Shadow" and "Harmony House." As a cis, straight white man I'm constantly trying to balance representation of all people in my writing with cultural appropriation. The last thing I ever want to do is hurt anyone or make them feel inconsequential.

For me, having a trans daughter changed many things, but most importantly, it's helped me to understand how important it is for queer people just to be seen and not completely ignored in the world. So, I've erred on the side of potentially getting it wrong sometimes in my fiction in service of being inclusive and expanding my palette of creative choices. You can paint so much more when you include all the colors. Thanks for writing this, and thanks for being such a generous reader and supporter of my work.