We Need Art Now!

A mini manifesto on the purpose of the arts & humanities in our world and wonder at those ignorant to its value (??)

The Saturday Brunch: a figurative flat white or fizzy to start your weekend

You could call this instead: Issue #1 — why I write this newsletter (there will be others).

The way we perceive our surroundings comes from our knowledge of the world as well as our own considerations of beauty (and truth). If we understand a view of the mountains or a room full of people at a party through science alone, are we not missing something? Are we not retreating into a world that could be duplicated by robotic beings?

I love science. And it surely matters. But it has been wrongly hierarchicized into the top rung of a ladder leading to perhaps longer lives and hopefully a way to save the planet when we simultaneously need reasons and ways to live. We need a matrix of understanding. Without a reason, without beauty, what’s the point of saving the Earth anyway? Isn’t this why so many shortsighted world leaders are ignoring what we need to do to tackle this problem?

[Although Elon Musk continuously articulates that he does not want to live forever, my husband’s greatest fear is that he lives to see the day that Musk’s mug - and brain - is attached to a new body (a clone?) to allow him to live on and on and on…gaining more and more wealth for lackluster (evil?) purposes. Anyone else horrified by this image? I get to imagine it once a week.]

When I started out working on my PhD in Comparative Literature, somebody close to me actually scoffed, “Well, it’s nothing like a science degree.”

Of course it’s not. I mean, each degree is different. But if the intention was to claim a higher value or difficulty…maybe they know something I don’t know about the world and how it’s really cool to live in a place without art…literature…culture…ethics…law…. Could we somehow make an easier world of black and white where decisions are obvious and we stay alive by protein powders and UV lights? Where truth doesn’t really matter because, hey, we’re all just staying alive?

Yeah, maybe, like Frankenstein’s miserable monster brought back to life without considering the implications or the clones living in the massive basement complex-lab in The Island (2005):

I really do love science. Don’t get me wrong. I almost majored in chemistry in university. And I’ll take every (tested) vaccine that’s coming! It’s just that the best scientists also consider ethics, emotional impact…humanity. Conversely, the best artists and generally people working or thinking within a humanities frame, are better off considering science.

There are examples of these interdisciplinary creatures everywhere. The great poet William Carlos Williams, who was a doctor by day. Leonardo da Vinci, Renaissance Man extraordinaire. Einstein was a devoted violinist. Brian May of Queen has a PhD in astrophysics. (Here are a few more famous ones.)

The particular scientist who condescended my degree also loves the arts as well, so the comment was probably from a different (human) place inside that can be influenced by the media, economic and education systems, or even jealousy.

Who knows? But even those who don’t say it aloud sometimes think within this hierarchy, because it’s something that’s been taught to us. It is the paradigm of the twentieth century that has only gotten more entrenched in the last two decades. Why should professors in English departments get paid the same as science professors when their graduates likewise have lower earning potential, and therefore less available to give back to the university? When all they do is spend their time reading books? Sigh.

[If you’d like some inspiration or you’re trying to convince someone else (such as your parents if you’re in school), just look at the Guardian’s “What an English degree did for me,” featuring novelists, musicians, executives, politicians, and even a horticulturalist.]

The very fact that this post and other articles exist proclaiming the need for art or the reasons studying literature is ‘good’ astounds me. I know I’m preaching to the choir if you’re reading this newsletter, but isn’t it obvious? Why can’t we shift the dominant narrative?

ART = Human = Creativity = Freedom

My theory depends on the fact that every human being is an artist. I have to encounter him when he is free, when he is thinking. Of course, thinking is an abstract way of putting it. But these concepts—thinking, feeling, wanting—are concerned with sculpture. Thought is represented by form. Feeling by motion or rhythm. Will by chaotic force. -Joseph Beuys

Without the arts, philosophy, all humanities…who are we? A good artist and thinker will understand the world also by understanding science. Perhaps they will not solve a problem of physics or genetics, but they can understand what a scientist discovers in order to see, to create, to decide. They can collaborate to create meaningful projects or policy to propel us forward.

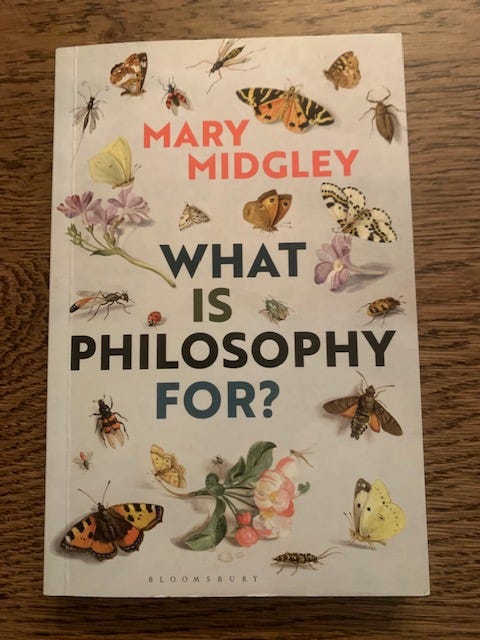

Essentially, this is the argument of the philosopher Mary Midgley in her last book, published in the same year as her death in 2018: What is Philosophy For?

Midgley is discussing the need for philosophy, but she also discusses a need for valuing the humanities in general and the needs of a philosopher in bringing together all areas of research and production or creation. In other words, the silos should exist to propel deep knowledge, but they should hang out together sharing knowledge at cafes or chatting on online platforms…everyday.

Here are a few examples of what she does in the book:

Tackles the notion of free will as a matrix of medicine, quantum physics, spirituality, human emotion, and more (pp. 41-46)

Investigates the dangers of too much “specialization,” rather than scientists who are determined to ask big questions and make “bridges” between ideas (pp. 15-20)

Discusses the human “search for certainty” and the dangers of limiting ourselves in this way (pp. 125-6)

Midgley further explores the malconstructed hierarchy of subjects during the twentieth century:

From the scientific point of view, other forms of scholarship - history, poetry, philosophy, ethics, theology, the arts, the social sciences, which so far have all seemed to be necessary aspects of life - now appear as subsidiary approaches, provisional suggestions, minor arts that need confirmation from physical science - indeed, if possible, from physics itself - before their results can be treated as conclusive. (p. 113)

And goes on in the same chapter to discuss the way “value” has been attributed to scientific truths (only):

In short, the only thing that has any real value is held to be the pursuit of truth - not just any old truth but truths about the physical world, found out through physical science. Other human ideals and standards are not considered to be valuable except in so far as they serve this purpose. (p. 115)

In other words, everything else is seen as wishy-washy. Midgley’s book-long thesis is that the wishy-washy non-black&white answers are the more difficult questions and the ones that should be valued. But she does not attempt to move the non-sciences above either. She wants science to reclaim philosophical values and to work with the humanities.

Of course, many do this kind of work. We need these people to be valued! Why can we not deconstruct the opposition created between a science-rational world and that of lofty artists?

Relatedly, there is a great interview with the NYT with Jennifer Doudna about her lab and her research on CRISPR gene-editing technology:

I don’t mean to put it pretentiously, but your work involves touching the fabric of life itself. Has doing that work given you any wisdom that you can pass along to younger scientists? And I don’t mean something like “If you try your hardest, your career will work out.” I mean deeper wisdom about the relationship between humanity and science. But I’m asking from an ontological or theological perspective. What thoughts does having your hands in there editing DNA spark about our place in the universe?

It does seem quite profound that just in the last few decades human beings have figured out “What is the genetic material? What does it look like? How is it replicated?” and then, increasingly, “How do we synthesize it, change it and, now, how do we edit it?” It’s not something that we could do today, but you can see all the technical pieces have come together that would allow us to, for example, make the DNA that would encode an entire organism. With CRISPR, you could imagine doing things with life that have never happened in nature but now are possible because we can alter the DNA at will. That is a profound thing. I’ve asked myself, and I think this is kind of unanswerable: Is this a natural progression of human curiosity about who we are, why we’re here, what is life? All those profound questions that scientists have been trying to answer by trying to uncover the actual chemistry of life. Now we have a lot of that knowledge. We’re still, in my opinion, very limited in our knowledge of what our genome actually does, but we have tools that allow us to start to uncover the remaining answers to those questions more quickly. So where are we headed with that? It’s a hard question to answer. If we were on a steady trajectory, it would still be hard to answer, but we’re on this accelerating trajectory. I’m thinking about computing, machine learning, all the hard tech that will change and accelerate the pace of discovery.

The whole interview is worth a read. Essentially, she is asking for philosophy and humanities to come in; relatedly and inversely, she earlier states that “at some level, we’re all scientists, because being a scientist is about being curious about our natural world.” Perhaps one solution to our problem of hierarchy and opposition is through journalists and other writers who give voice to people’s stories working in the in-between, proclaiming truth that is found through interdisciplinary frameworks.

Liberal Arts education

There have been a slew of articles in the last ten years or so about holding onto liberal arts, something in danger of being lost in America and something seen as frivolous from other national perspectives where academic specialization happens much, much earlier (you essentially pick your major in 8th grade here in Switzerland).

David Brooks of NYT wrote “The Humanist Vocation” in defense of humanities just after “the American Academy of Arts and Sciences released a report called ‘The Heart of the Matter,’ making the case for the humanities and social sciences” (he was a member of the committee working on this as well).

The New York Times must have a bunch of liberal arts graduates on staff, because they write about this topic a lot! (Or they are just really wise…) Frank Bruni for NYT writes a response to this discourse in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

I worry that the current conversation about majors is part of a larger movement to tug college too far in a vocational direction.

And I worry that there’s a false promise being made. The world now changes at warp speed. Colleges move glacially. By the time they’ve assembled a new cluster of practical concentrations, an even newer cluster may be called for, and a set of job-specific skills picked up today may be obsolete less than a decade down the road. The idea of college as instantaneously responsive to employers’ evolving needs is a bit of a fantasy.

NYT has published many Opinion Letters in response as well to each of the above articles, such as “Don’t Scrap the Liberal Arts Major” (this one from someone with a PhD in Comparative Literature, working in postsecondary opportunities): “Smart schools are encouraging students to major in liberal arts, but they are also coupling practical career and professional training with them.”

This type of education is my frame. My undergraduate alma mater, Bowdoin College, explains their commitment to a liberal arts education:

The academic disciplines are specialized modes of inquiry through which human beings perceive and intellectually engage the world. Both their power and their limits have led the College to make a long-standing commitment to general education. Specialist faculty cause non-specialist students to become critically acquainted with the perspectives and methods of disciplines in three general divisions of learning: the natural sciences, the humanities and the arts, and the social sciences. The College also sustains programs of interdisciplinary study to reveal complicated realities not disclosed by any single discipline. It requires study outside the perspectives of Europe and the West; and it encourages study abroad to foster students’ international awareness and linguistic mastery.

At Bowdoin, I began knowing I would major in English (literature) but playing around with chemistry and environmental studies as well as whatever looked interesting, ultimately choosing my second area of study in art history. None of this feels like a waste of time. In fact, many of my college papers drew on ideas from other disciplines I was simultaneously studying. Physics helped me consider colors in my painting class in a new light; intro to environmental studies was taught by a philosopher, biologist, and economist, constantly entangled in debate during our lectures.

One argument against is that some think these degrees are lofty without practical use, but many schools have practicality alongside liberal arts. Additionally, the world of work is changing quickly, and we may not understand the needs of work, which may very well be this kind of creative and flexible thinking across disciplines.

To become a teacher, I did need a practical degree as well. I could have done this at Bowdoin, but most states require a masters anyway, so I waited and did my degree at Boston College. This was expensive, and I had to take out a big loan to do it. But it was also a great time to synthesize what I had learned into something useful for myself and my future students. At BC, many of our courses were with other grad students who were aspiring teachers of various disciplines, so we were in constant interdisciplinary conversation.

In secondary schools, I mainly taught English language and literature, but this means a lot of things now. In addition to traditional types of literature and writing skills, we teach film, social media, song lyrics, and more. I also taught some art classes. But the really fascinating thing I started doing in an international school in 2007 was teach Theory of Knowledge, a course of epistemology and applied ethics, but also one that was completely interdisciplinary. We investigated knowledge through the Ways of Knowing and the Areas of Knowledge. Check this out if you don’t know about the course. While the assessments could feel rather forced and dry, the day to day teaching and learning (reciprocal with my students) was such a joy.

In Hong Kong, I was in the Comparative Literature department for both another masters and my doctorate. Some have declared comp lit dead, but HKU looked at it freshly. It had become an interdisciplinary discipline. We studied culture through the arts, looking mainly at literature, film, and critical theory, but also multimedia and new textualities. We learned from and collaborated with law, philosophy, and history professors. We worked from more than a ‘translation’ framework, embracing internationalism. I really felt like that intellectual space I was immersed in there was the future. I’m grateful for it, and grateful that although - sadly - HKU may never be the same place again, some are bringing their work elsewhere, like Dr. Gina Marchetti at Pratt.

I tell you about my journey to show how ingrained liberal arts and interdisciplinary learning is to me. You might say it only works because of the particular journey I had, but conversationally, my classmates who became lawyers, doctors, and even bankers found a lot of value in learning this way as applied to their professional lives, whether in ethical considerations or finding a greater purpose in their work or understanding the way art affects their psychiatry patients. The other two founding members of the Bowdoin Literary Society became a doctor and lawyer.

Part of the issue might be that we place too much value on learning’s direct causal relationship with jobs and money, when there is also a lot more to the world.

Value / Money

We need to acknowledge that art and artists require money. Artists should not be expected to suffer in poverty simply for a life of creation. Believing such would deprive the world of great potential and risk the untimely demise of many rising artists who are likely to pursue something elsewhere or may literally reach a demise due to the depression associated with their unsupported undertaking (though it is one they understand to be of importance).

Universities can tackle this disparity but so can those giving out grants. Taxation can attempt to level the playing field as well, in a redistribution of wealth. I’m not talking about communism here, but a person rich from their banking investments should want to live in a world with the arts, and in a place where philosophical thinkers are deeply knowledgable in history and sociology rather than only the area of economics, for example, that they are advising. Let’s pay the social workers, kindergarten teachers, and muralists making your city beautiful enough money to live comfortably.

We also need to protect the work artists do (à la Taylor Swift discourse) as well as the artists themselves. Freedom & Creativity: Defending art, defending diversity is a book by Laurence Cuny available for free on the UNESCO digital library. It discusses, among other things, the need to fight for protection of online rights of publication for artists as well as protection for artists who may be attacked for their work, due to politics or religion.

As artist Moses Kabaseke from the Democratic Republic of Congo says: “As the number of my followers increase, my personal insecurity increases. Personal safety is essential as an artist talking about human rights” (p. 31). Immigration status is also important; if a person is considered ‘illegal’, how can they speak up or create without fear of repercussions? Cuny quotes Valerie Oka: “When speaking about artistic freedom it would also be necessary before, maybe, to speak of the status of the artist, because before being free to express oneself one must legally exist” (p. 28).

Like the imaginary writer in Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own,” all artists / all people need some space and some money to do their work.

Why now?

What about the “NOW” part of the title of this commentary? Do we need it more than ever? Or is it the fact that it seems to be slipping away from us? The call to action is the act of not losing it forever…as it ebbs out of curricula and public spaces and from lists to donate money to. It seems no mystery to me that the erosion seems to be happening simultaneously with the loss of our earth. Science has a lot of the answers here, but why will people want to act? How can we make the right ethical choices? What are we saving it all for anyway?

It’s not only climate change. With the pandemic, extremist politics, the return of war to Europe, and rise of our time spent on our phones…it can feel like a really messed up place. Unless we stop. Make sense of it. Find hope. Learn how to rise above. It’s amazing that we can make vaccines for COVID in such a short amount of time and amazing that we can help so many refugees escaping from war zones (although much, much more can be done). Sometimes the voice of an artist, whether through writing or song or paint, can help us to move beyond these feelings of doom. I wrote about this when discussing Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, and with a reference to other musical acts and films.

Where are the helpers? They are all around. They are the scientists and the philosophers. They are the photographers and the mathematicians. They are the teachers and the news anchors. Or at least they can be. Let’s all work together for a better tomorrow.

We need to infiltrate the minds of others with this message. Or, we’re doomed.

Can we keep sharing this idea? Can we keep acting on it? Whether in conversation or creation or policy…

This is just the beginning. Let’s talk later about how art affects us personally and as communities. I just want to be clear: art’s not an extra for (human) life. We need it. Who’s with me?

Further reading & listening (in case there’s anyone - especially with money and power - you’re trying to convince):

Why We Need the Humanities (book, 2016)

“Why do we need the humanities?” (The Conversation, 2015)

“Why Is Art Important? – A Holistic Investigation into the Importance of Art”

(Art in Context, 2022)

“We Need Art in Our Homes. Here’s Why.” and “Why We Need Art in Times of Crisis.” (Artwork Archive)

“Why we still need to study the humanities in a STEM world” (Washington Post, 2017)

Not Real Art podcast, July 2021:

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

I'm with you, Kathleen! Being a mature student, I faced many of those conversations too: "why don't you study something more 'practical' than English Literature..." I always retort with the same answer, as you suggest: "who would want to live in a world without music/film/books/art/newspapers..." Great post - I am just catching up on your archives : )

Beautiful post, Kate. It reminded me of the historian Jill Lepore podcast The Last Archive. At one point, she was discussing just how data driven our time has become. Everything, it seems, can be broken down and studied and furthered through data. To the point it can feel like nothing else matters. Lepore protests that there is a truth, unlike what data captures, that can be conveyed in a poem. Art can express, celebrate, and share truths that elude data. I also think about how without exaggeration technology has in certain ways given us god like powers. I believe in order to wield those powers responsibly or decide if they should be wielded at all depends more on a liberal arts type education than the technology education that created these powers to begin with.