Part of the ongoing series on Nature and Transformation

I love to go out in late September

among the fat, overripe, icy, black blackberries

to eat blackberries for breakfast,

the stalks very prickly, a penalty

they earn for knowing the black art

of blackberry-making…

excerpt from "Blackberry Eating," by Galway Kinnell, 1980

Perhaps you expected the orange, brown, yellow, and red warm colors of autumn to adorn the top of this page? But autumn has the full spectrum. These dark cool colors expose another side of autumn, of the “black art” of poetry making. Kinnell’s poem is my favorite metapoem, exposing the way “the ripest berries / fall almost unbidden to my tongue.” The cold silence of September after the heat and music of summer give the poet a reflective metaphysical space for his writing.

Autumn has plenty of music, too, and I’ve created a short playlist to go along with this week’s exploration. Feel free to listen as you read:

My birthday falls on the tenth day of autumn. I like this time of year. It is one of reflection and, for me, freshness. Some see spring this way, but I have always worked off of academic calendars, so autumn comes about a month into ‘the year’ (as does my birthday). I’ve had a busy start to something – teaching, learning – and now it’s time to check in. How is it going so far? What do I want to accomplish this year? How have I grown since last year? The cooling air helps me to feel more alive and wake up to whatever reality I want to create for myself.

People travel to my native New England, Vermont especially, for the pure beauty of the fall foliage. There are many places around the world that have their own version of this phenomenon. Where I am now - in Switzerland - we have it, too, but this year, because of the summer drought all over Europe, the leaves outside my window turned quickly to brown and fell in mid-August. They have already been raked off of the ground. I can only hope this extreme summer sparks stronger movement from governments to fight climate change.

Perhaps similarly optimistic, the leaves falling, for me, don’t signify the end to something, or a harbinger of death. Instead they are a chance at a fresh start, more like a haircut. The winds of change open me up and freshen me. The rains of November cleanse me in preparation for the introspection of winter.

Perhaps the oft-used metaphor of autumn as a kind of movement toward death isn’t a pessimistic one anyway. Does it not allow us to consider why we are living? And why we cherish the things that live around us? The transformation reminds us that the Earth is moving on its axis around the sun, making us feel small to the wonders of the universe.

Or…it is simply a nice season to wear a sweater, bake a pumpkin pie, and take a walk without sweating or getting frostbite? There are many layers of autumn’s pleasures.

This year, I’m going home for the month of October. I’ll be in New England in autumn for the first time in many years and will talk about this home-place during the next couple of weeks. But for now, I want to remain in the abstract, in the liminal spaces created by a recurring time.

Autumn poems

Autumn always feels ripe for poetry, as if the wind and falling leaves carry in a simultaneous mood of something between nostalgia and melancholia and fresh alertness to one’s surroundings. For me, who has always been a student or worked in schools and universities, it has always marked the start of the year. The cool air awakens me to the new people and ideas I will interact with.

Literary minds cannot talk of autumn without conjuring John Keats and Robert Frost. With Keats, the choice is obvious. One must look at “To Autumn” (composed on September 19, 1819; published in 1820); here is an excerpt, the last of three stanzas:

Where are the songs of spring? Ay, Where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

Keats also finds joy in the “music” of autumn. He found a great amount of beauty during such a short life. Bright Star (2009)is a dramatization of that dreamer’s life. His three stanzas mimic life’s transformations in an ode to the beauty of the season itself, as if a myth-like creature that propels us forward with her wind.

Many consider it one of the best poems in the English language. But sometimes in the sheer appreciation of its aesthetic beauty, we forget its place in history. Autumn is not the same every year; its recurrence also reminds us of the changes within and around ourselves each year.

In “Agrarian Politics and the Economics of Writing: Keats's ‘To Autumn’” (1991), Andrew J. Bennett discusses the ‘perfection’ of the poem as well as its place in a political time, considering the nature of poem writing as ‘work’ for which to be remunerated. Paul H. Fry’s “History, Existence, and ‘To Autumn’” (1986), on the other hand, investigates the impact of a “good harvest year” in 1819 and other elements of socio-political history in the poem: “even the countryside is enclose by the hedges and crofts of history, and that Autumn itself is a leisure class commodity produced by field hands too worried about the coming cold to notice the pleasures of merely circulating” (p. 211).

Robert Frost, who lived until he was 88 (vs. Keats at 25), gave us many more autumn poems, such as “October” and “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” He lived in Massachusetts and Vermont for most of his life, often using the seasons as subjects of his poetry.

My favorite autumn poem by Frost is “After Apple Picking” (1915), which similarly to Keats, takes us through a persona’s transitions. Frost’s persona is more explicit and anecdotal as a human figure. The beauty also lies in the diction and rhythms of his language as well as in the understanding of underlying philosophical questions about childhood, aging, and death.

Here is an excerpt from the middle of the (single-stanza) poem:

Magnified apples appear and disappear,

Stem end and blossom end,

And every fleck of russet showing clear.

My instep arch not only keeps the ache,

It keeps the pressure of a ladder-round.

I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend.

And I keep hearing from the cellar bin

The rumbling sound

Of load on load of apples coming in.

For I have had too much

Of apple-picking: I am overtired

Of the great harvest I myself desired.

The short sentence stops suggest the slowed movements of the persona considering that he has come toward death or at least a new phase of life, perhaps more settled and less exploratory. Of course, apples are symbolic of many things: knowledge, sin, temptation, immortality…even love.

The persona wants a “sleep,” likening it to that of a “woodchuck” (hibernation) or “just some human sleep.” So perhaps he’s not talking about death at all, just a rest, just some time for reflection.

After all, in my experience at least, apple picking starts as a joy and quickly becomes a chore. Sometimes we need to step away to appreciate life’s joys again.

Autumn in a seasonal series

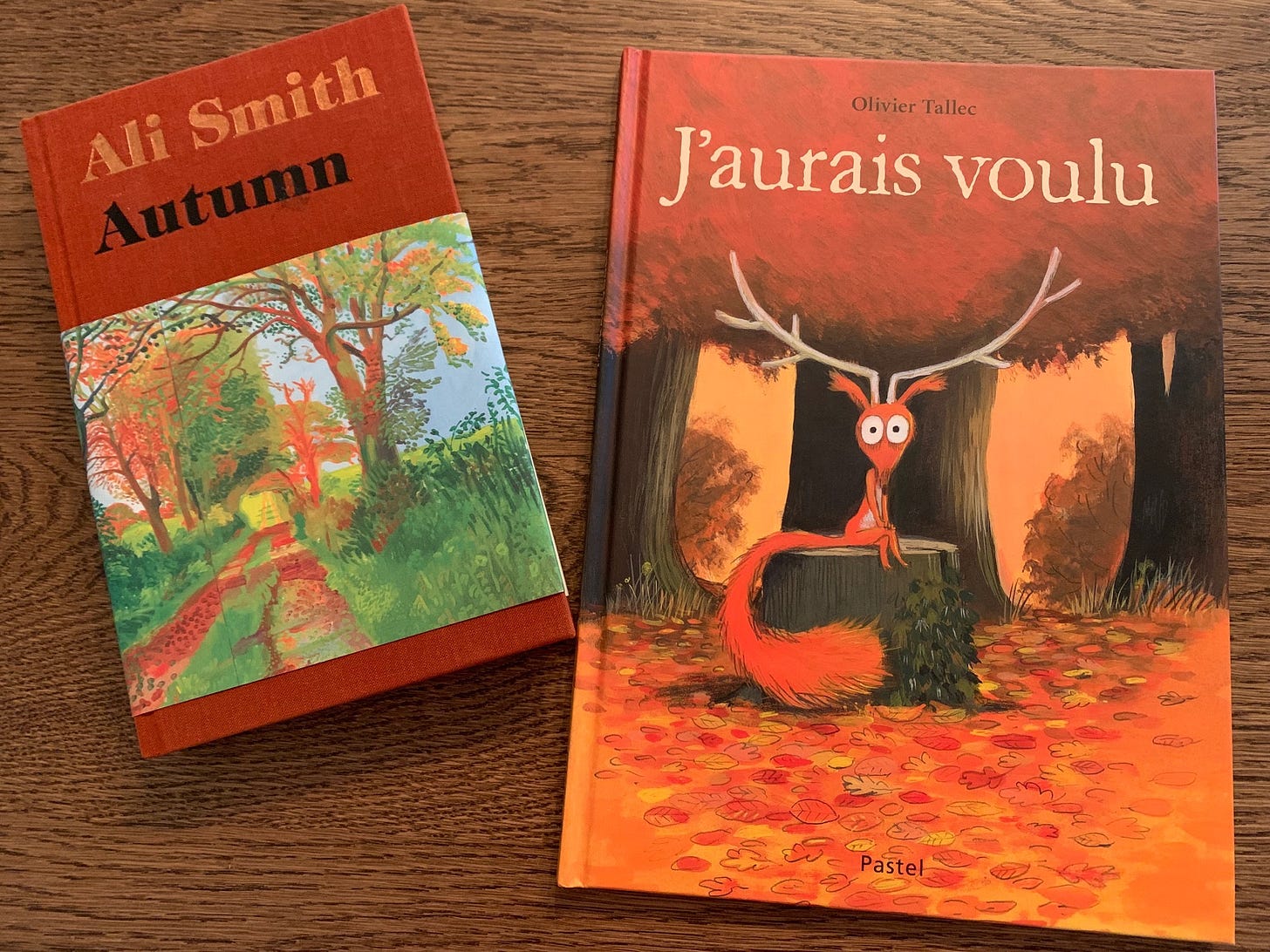

Ali Smith’s Autumn (2016) is the first in her seasonal quartet series.

The cover, as with the others of the series, is a beautiful digital painting by David Hockney. (He has his own ‘Four Seasons’ which you can view here.) Could they be the most beautiful covers ever created? Even if one takes off the Hockney book jacket, one is left with a warm brown cloth, indented embossed author and title, and complementarily-colored turquoise endpaper.

Smith opens with a multi-allusional entry as she likens “an old old man washe[s] up on shore” metaphorically to the time of year (p. 3):

It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times. Again. That’s the thing about things. They fall apart, always have, always will, it’s in their nature.

…

I’m ground so small but in the end I’m all, I’m softer if I’m underneath you when you fall, in sun I glitter, wind heaps me over litter, put a message in a bottle, throw the bottle in the sea, the bottle’s made of me, I’m the hardest grain to harvest to harvest

Her allusions to Dickens (A Tale of Two Cities) and Yeats (“The Second Coming”) help us consider allegorically the writing of her 2016 tale of a world that feels fractious. (The Gaurdian considers it the first post-Brexit novel.) But she also looks at the cyclical nature of things, giving us hope that they will turn around.

The book is about more than political allegory; it is also about individual time and mortality and the way we experience the seasons of our lives. Keats’ poem seems to be in the background without explicit reference throughout the book, but the poet who died so young makes an appearance: “By the time ‘Autumn poet’ John Keats pops up, we are fully immersed in the nightmarish dreamscape of Daniel Gluck. Keats died young but Daniel is old; in his feverish thoughts he lies washed up on a beach, surrounded by bodies and contemplating his mortality.”

At the end of the novel, it is “November again. It’s more winter than autumn” (p. 259). One expects an even worse place heading toward doom, but she goes on to talk about a the roses (p. 260):

But roses, there are still roses. In the damp and the cold, on a bush that looks done, there’s a wide-open rose, still.

Look at the color of it.

Smith reminds us of hope and beauty despite some aspects of a depressing world. She breaks the fourth wall to tell us to “[l]ook.” We are then given agency by he words.

Similarly French filmmaker Eric Rohmer made a series of seasonal films, although his ends with autumn. Autumn Tale (Conte d’Automne, 1998) brings together second chances at love, winemaking, and a small community. It’s more lighthearted than Smith’s book but similarly investigates human time and our interaction with the seasons that repeat within our lives.

These roughly connected seasonal artistic explorations allow the artists to play with seasonal metaphor in new ways and create a more epic multifaceted portrait, whilst avoiding the sequel. This is not unlike Kieslowski’s Blue - White - Red series, although he utilizes the colors of the French flag.

Painting a moment

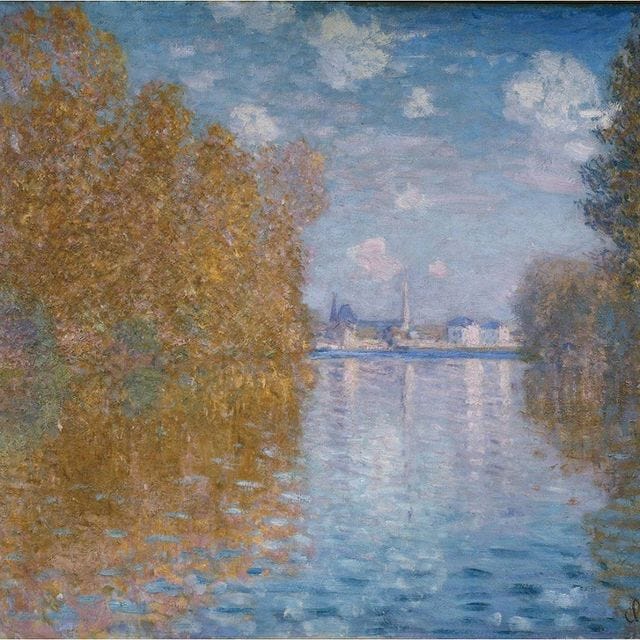

Impressionist painters were also famous for capturing the seasons and for showing the vivid colors of autumn as well as the movement the autumn wind has on the landscape. Impressionists often focused on the passing of time and changing light in their work. You might consider images of Claude Monet’s prolific series, which showed water lilies or cathedrals in different seasonal settings.

Monet’s “Autumn Effect at Argenteuil” (1873) is as much a play of color and light as it is a subject with meaning. The painting has a clear vanishing point that draws the reader in, as if floating down a boat on the river. The reflection of orange leaves on the water is both realistic and shows us that the world can be quite abstract and unexpected if we look more closely. The contrast of the green trees on the other side of the river suggests that we all move at our own pace; that people transform when they are ready.

Daily Art Magazine has a wonderful list with images of other famous autumn works of art, and David Guinn’s street art (“Autumn” and “Autumn Revisited”) is worth taking a look at.

We might consider how a still shot exploration of autumn magic is different than poetry, books, and films in the way it mimics a moment in time. If we consider time as a subject, how does a painting paradoxically immortalize a fleeting moment? How does it make us reconsider our subjective experiences of time? Does it not suggest that we could slow down time forever?

Kids and the philosophy of change

Kids often think about traditions instead of the changing weather, which they just roll with. In autumn, a New England kid might want to go apple or pumpkin picking and may start considering a Halloween costume or jack-o-lantern design. They might consider what sports season starts during this time of year (wherever they are based) and who is going to visit at American or Canadian Thanksgiving (and what movies they’ll be able to watch, such as Charlie Brown specials).

The Peanuts kids seem to suffer and philosophize more like adults in the autumn. They play sports in cold, rainy weather. They wonder about the death of a leaf. They take joy in the beauty of nature.

It’s not just an adult superimposing seriousness on children, but a real reflection of the world of kids that is also philosophical. If we really listen, we can hear the great ideas and questions they come up with on a daily basis. I learned this during a year teaching art to elementary (primary) school students as well as through the musings of my almost-four-year-old at home. I showed the second graders a clip of Peanuts before working on autumn crafts I had learned as a child. They came up with unexpected ideas while their hands were working and told me tales of memories from their own autumn experiences, sometimes in other lands.

[Craft aside: One of those gorgeous art students in grade 2 engaged in a philosophical discussion of craft vs. art with me one day while we were making Romanian sorcova. If you’ve got kids or you just like doing things with your hands, why not make some art of autumn things like leaves, pinecones, acorns, and more? Here are a few ideas from The Imagination Tree.]

The autumn reminds us that kids are growing up and observing their surroundings. What are your memories as a kid during fall? What do the children in your life teach you about being comfortable with change?

Olivier Tallec’s J’aurais voulu (‘I would have liked…’, 2021, cover above) tells the story of a squirrel who wants to be anyone but himself. Although the story is not about autumn, its setting makes for beautiful watercolor paintings as well as an added layer of meaning. The squirrel bounds through a multicolored forest, kicks mounds of leaves in frustration, and picks blackberries while trying on the identity of a hedgehog. After posing as many animals of the forest, he decides that, actually, he likes being who he is: a squirrel.

During the fall, I notice more, because all seems to be moving and changing. Again, this year I have greatly changed. This newsletter is something new. Feeling at home in Basel is something new. Other things are not, but I can experience them again…for the first time. I will hike atop the crinkling leaves and sit outside at a cafe with my family, moving closer as the wind comes in.

How have you changed and how do you plan to make the most of your autumn? What is lurking in that liminal space…

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

I guess I'm an autumn guy though most of my memories - especially of when I was a kid - are connected to endless summers at the beach.

I like autumn's melancholy, its colors and softer vibes. Something like this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzQ9NCGHGaw (the whole album has an autumnal feel)

Ah, thanks for mentioning Eric Rohmer. He's one of my favorite film directors.

I have to say that I am like you - I always feel a fresh start feeling at the beginning of Autumn. I don't know whether it's a hangover from school days, or because I have my own children. I also live in a University city, so September sees the students drifting back and gives the city a buzz that I love! It always makes me want to hunker down and read and study, which is partly why I decided to start a Substack : ) I hope you have a lovely 'homecoming' visit!