Part of the ongoing series on Power and Creativity.

Last week, we took a look at personal soundtracks. The music and sound that accompanies experiences, memories…real life. Now we apply some of those ideas to soundtracks of art forms.

When we think of a soundtrack, perhaps most of us will consider that of a film’s musical score. We can use that as a starting place. Sometimes a song even sells a film to us before we see it. When helping high school students to understand mood and tone (and the difference between them) we would often look at film clips with non-diegetic music in order to understand a filmmaker’s intentions.

The same thing happens when we see a preview with music: we should get a taste of the feel of the film. The music in Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby (2012) trailer featured new music from Beyoncé and Andre 3000, Lana Del Ray, and Florence + the Machine, which told even those unfamiliar with Luhrmann’s oeuvre that this would be a different, edgier version of the novel. It works for television, too. The trailer for the 2006-7 Life on Mars series with the identically named 1973 David Bowie hit used for the theme music made me love it before I could really figure out what the show was about.

Surprisingly (to me, at least), the first full length film soundtrack release was from Disney’s Snow White (1937). Many other Disney and children’s films have gone on to release coveted albums, including the more recent Sing and Frozen films. Some of the songs were hit singles at the time and even decades later in 1993, despite challenges to recover the original music, Disney put out a re-released version. Producers Randy Thornton and Michael Leon tell us: “Luckily, we were able to locate ‘Snow White’ nitrate optical instrumental tracks--just as they were about to be shipped off to the Library of Congress storage vaults.”

1993 was still the days of Tower Records, pre-dating the dawn of digital music by four years. Selling an album was a way to make money. However, it was also a unique aspect of the artistry of filmmaking and one that not only brought music to life in different ways but also sparked the creation of great songs made specifically for a cinematic vision. This is why it continues beyond the need for record sales and why, perhaps, it has expanded into other artistic mediums.

[Today’s Spotify playlist link - not visible below on the Substack app.]

Films

Of course, all films (unless silent) have soundtracks and most include songs. But some make more explicit use of musical soundtracks that seem to define and sometimes even surpass the film itself.

Films began silent, then added a single track of music, and finally more complex sound-tracks of voice, music, sound effects, etc. But during the silent phase, live piano playing often accompanied the art. My great grandmother used to play the piano during these performances, which I guess was seen as a rather mundane working class job at the time, but as I view it through a historical artistic lens…I am amazed. Some film festivals reenact these live performances. And then there are other creative ventures like this live orchestra in front of a Gladiator screening.

You can read more about Deleuze’s ideas of a sound-image relationship here. And if you are a student or teacher of film, here is a good list of vocabulary to talk about the sound in a film as well as an overview of film sound history.

Top Gun (1986) is one of the first iconic film soundtracks to spring to mind, maybe because of the recent Maverick sequel. One could argue the music is better than the film…although Val Kilmer as Iceman is certainly memorable and it was cool to see him reappear in the sequel despite his health issues (have you seen the documentary?). Isabella Soares tackles the question of why the soundtrack is so iconic, linking it to the intensity of key moments in the film but also a range of genre with the ability to appeal to multiple audiences.

I’m not certain why, but I did own the (eek) cassette in the 80s. The songs recently returned to my ears thanks to the fun young children I taught art to last year. Occasionally, they would select songs for the class to listen to while we were painting. The third grade boys were obsessed with music from Top Gun. I don’t think they had even seen the movie. The music itself seemed to sell them some idea of cool or masculinity or energy. They also enjoyed Ed Sheeran and Katy Perry, so I was pleased with the eclectic nature of their selections and allowed a few nostalgic minutes that perhaps their parents had subjected them to at home.

Just a year later in 1987 and just as iconic, came Dirty Dancing in the category of 1980s dance films, probably influenced by the start of MTV. I’m sorry if this is too cheesy for some of you, but I have to paste Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes’ “Time of my Life” here, just in case the younger generations here haven’t seen it. And anyway, I think a little cultural cheese is good sometimes.

Musical soundtracks tend to be in the non-diegetic sound category, like the music of pianos that used to accompany silent films. That is, sound that would not be oriented in the world of the film itself. But occasionally, songs are included in a way that characters are listening to them or even singing/playing themselves. This adds a different level of meaning to the musical texts contained within the larger filmic text.

Dirty Dancing uses a combination of these types of music — either as background to set the mood or as music for the dancers to perform to (which also sets a mood, but is a performance within a performance, making the characters’ reactions to it more complex). One could argue that music comes alive a little more when the characters are also responding to these sounds.

A decidedly edgier Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) also uses a combination of diegetic and non-diegetic music and has an iconic dance scene whose moves are also decidedly easier (and safer) to mimic. The album also included a few sound clips, such as Royale With Cheese:

“You know what they put on French fries in Holland instead of ketchup?”

“What?”

“Mayonnaise. [laughter] I seen ‘em do it, man. They f***in’ drown ‘em in that s***.”

Rolling Stone has a nice roundup of the album but leaves this part out as well as a discussion of “Zed’s dead, baby. Zed’s dead.” Are these not, by inclusion in the album, spoken word songs? Or are they simply marketing tools, teasers to go back and view the film in whole?

Tarantino uses music as part of his storytelling device. He tells us in the booklet accompanying “The Tarantino Collection”:

One of the things I do when I am starting a movie, when I'm writing a movie or when I have an idea for a film; is, I go through my record collection and just start playing songs, trying to find the personality of the movie, find the spirit of the movie. Then "boom" eventually I'll hit one, two or three songs“ or one song in particular, oh this will be a great opening credit song.

Because to me the opening credits are very important because that’s the only mood time that most movies give themselves. A cool credit sequence and the music that plays in front of it, or note played, or any music“ whatever you decide to do“ that sets the tone for the movie thats important for you.”

The frame of a film: how often do we now skip through an opening or turn a film off during the credits? Some filmmakers encourage us to pay attention by continuing part of the narrative as a sort of bleed beyond the contained film. More than outtakes, one might see something along the lines of an epilogue, which I witnessed while taking my son to see Minions: the Rise of Gru partly because we still had a load of popcorn to eat up.

Richard Linklater is another auteur who takes his soundtracks seriously. Here he is on the music of Boyhood (2014):

The linking of music to the passing of time in a bildungsroman-style film demonstrates music’s connection to memory, youth, and identity as discussed last week.

[Aside: how many other 90s teens out there saw The Breakfast Club (1985) during a Life Skills class and mostly you can remember the music, like Simple Minds’ “Don’t You Forget About Me”? In my case, the teachers showed it twice. The film was already a decade old, so I’m not sure how much it showed us about contemporary teenage life, but it was a great movie…]

If we were to change the music to this film or others, would it change what the film said? Similarly, if we were to have different soundtracks to our experiences, would it change them? Or change our perspectives? Does the music of our generation (or the music we choose to listen to) determine our understandings?

Collaborative composition

In a different category is the relationship between John Williams and Stephen Spielberg who began working together 50 years ago. To date, they have made 26 films together. Perhaps because Williams was also the Boston Pops Orchestra conductor at the time, many of these compositions entered our high school concert repertoire; they are easy delights but also high quality music.

Recently found footage shows Williams and Spielberg composing E.T. together:

Director Guy Magar “salute[s] them as the greatest and most productive divine union between a director and a composer in the history of motion pictures.” The sounds created by Williams’ compositions are often fresh and unearthly (not only in the case of E.T.) but simultaneously human in the way we can connect more deeply with the films’ ideas.

Although Williams was capable of greatly sophisticated scores, he sometimes noted that a simpler kind of music has a stronger effect. The simple ‘DAAA DUMMM,” Magar further points out, can be easily identified as Jaws, even in writing. Spielberg at first thought this music was a joke, but Williams explains:

You could alter the speed of this ostinato; any kind of alteration, very slow and very fast, very soft and very loud. There were opportunities to advertise the shark with music. There are also opportunities when we don't have the music and, the audience has a sense of the absence. They sense the absence because they don't hear the 'dun dun' because you've conditioned them to do that.

Film scores about music

Then there are films that are about music. They offer much more than background music or beats that tap into a mood. Instead, they are a representation of culture, a mirror of the times, and often a reflection on the youth of that time period.

Empire Records (Allan Moyle, 1995) depicts young workers attempting to protect their independent record shop from becoming a large national chain. In essence, it is a struggle for cultural identity more than economic independence. As a companion piece, Last Shop Standing: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of the Independent Record Shop (Pip Piper, 2012) is a documentary about independent record shops and what they mean[t] to people.

Do digital spaces of music allow these similar interactions with culture and possibility of curation? Although we have access to much more and can reach a bigger network instantly, what do we lose without the physical space of music? Is this why so many have moved back to records and why record shops maintain a desired space of experience?

High Fidelity (Stephen Frears, 2000; based on the 1995 novel by Nick Hornby) also takes place largely in a record shop. The main character who works there attempts to use music to understand his life after a break up and eventually makes a mixtape to make his ex happy. The characters use music to express their likes and moods; poor Belle and Sebastian are vetoed by Jack Black’s character, who is looking for a little more upbeat energy. Their arguments over music and panning shots of the records and tapes within the film create an active dialogue and love story for music’s place in our lives.

Books with soundtracks

High Fidelity in novel version also has a soundtrack of music that runs through the text. Of course, you have to conjure the music in your mind or have your phone nearby and ready to search for the song allusions (something impossible at the time of the book’s publication).

Even now, one normally separates their music and reading experiences. However, brothers Mark and Paul Cameron have created a business called Booktrack that makes musical soundtracks for digital books. MPRNews also tackles this idea more informally through discussion and youtube.com playlists.

Gibson House Press, an independent publisher of literary fiction, also puts out book soundtracks with music from a wide range of indie artists. The project gives power to the author who is able to make their own Book Soundtrack. Each has a description on the publisher’s website, such as this one:

Esther Yin-ling Spodek channels the angst and humor in lives at the crossroads for her middle-aged suburbanite characters in her novel We Have Everything Before Us. Her playlist reflects what you might imagine hearing in the background of the novel’s parties, dinners, trysts, and conflicts – from Talking Heads to Norah Jones, Lucinda Williams, Queen, and David Bowie.

But their selections don’t focus on books with embedded soundtracks within them. It is their own creative layer to the text in dialogue rather than a realization of the author’s allusions. At least Gibson’s work is by the author themselves, making a multi-media text in the end. In reality, maybe these allusions wouldn’t fit with the mood of the text, and as several could be mentioned fleetingly, one would find it difficult to appropriately overlay them with the text. It seems to me the best method would be to pause and listen before moving on with the reading.

The music partly tells the story, not only through lyrics but through sound. Realistically, if we have to imagine this sound, it can be difficult to come up with the sound playing in the author’s (or character’s) head. We may not even know the reference. So, should a better reader pause to play the piece mentioned?

Allusions create intertexts

Because we all have our memories associated with music, allusions within texts can light up parts of our brain and activate a deeper, more personal reading of a text. However, they may also serve to alienate readers unfamiliar with the alluded work who are not interested in researching the references.

It’s not surprising that Haruki Murakami makes great use of musical allusions since he previously owned a jazz bar in Tokyo. Murakami rarely interviews, but tells us:

I’ve never learned how to write from anyone, nor have I studied in particular. So, if you ask me where I learned to write, my answer is music. Rather than learning a technique from someone, I’ve become conscious about rhythms, harmony and improvisation. If you think my books are easy to read, perhaps we have something in common musically.

His novel Kafka on the Shore (translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel, 2005), for example is rich with allusions to jazz and classical music as well as rock. For example: “He flips on the stereo. It’s a cheerful orchestral Mozart piece I’ve heard before. The ‘Posthorn Serenade’, maybe?” (p. 331) “In fact, the book as many other artistic allusions as well which The Atlantic has neatly compiled. World Literature Today has also created a unique soundtrack to overlay with the novel, but it does not draw on the allusions. I’ll say more about Murakami and his book-length discussion with Seiji Ozawa about music when we look at jazz.

Jennifer Egan’s novel A Visit from the Goon Squad (2011) mimics the form of an album itself. She includes music from artists such as Death Cab for Cutie, Tracy Bonham, and The Who (which the publisher has compiled for your listening pleasure / on publisher’s site). She discusses this aspect with The Washington Post:

Each chapter of “Goon Squad” presents a different set of characters loosely connected to the previous set; it’s a novel as record album, hinting at a larger narrative as it moves from song to song, from subject to subject. “Like an album,” Egan explains, “each story stands really solidly on its own legs, yet contributes to a broader vision in a vital way.”

Through song, Egan tackles existential questions, perhaps more poignant through our own experiences with music as we face the difficulties of life:

“I can't tell if she's actually real, or if she's stopped caring if she's real or not. Or is not caring what makes a person real?”

“Time’s a goon, right? You gonna let that goon push you around?” Scotty shook his head. “The goon won.”

“The answers were maddeningly absent—it was like trying to remember a song that you knew made you feel a certain way, without a title, artist, or even a few bars to bring it back.”

Academic David Hering considers the way “Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010) and Dana Spiotta’s Eat the Document (2006) use music as a way to problematize postmodern approaches to history and temporality” (“Play it Again…”). Although the music may help us have a deeper, more philosophical, or layered experience, the music may also simplify our existential questions. Rather than a postmodern explosion that lacks rationality, the music grounds us in a common human experience. Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis (2022) essentially has the same message: sometimes music can help us even more than words can. It can lift people up or unify them in grief. (Here’s my longer take on this film.)

The same could be said about the way the main character in The Hate U Give (2018) uses music to explore her place in America, in Black culture, and as a teenager. This recent novel by Angie Thomas is about a police shooting of a young Black man and the narrator’s fight to use her voice. It is classified as YA fiction, but I think it’s one for adults as well. Thomas was a teen rapper and music is clearly central to her narrative ideas. I love how she switches from TuPac to Taylor Swift seamlessly and with purpose. The musical allusions also serve to lighten the mood in a book dealing with tragedy. Jonathan Bradley has neatly extracted most of the musical references from Thomas’ book in this article.

There’s a film version, too, which plays neatly with the already present soundtrack (even the trailer starts with a discussion of music). It lacks some of the clever discourse and code switching in Thomas’ original text, but I think in this case, it’s such an important story to tell that even the limitations of adaptation can be overlooked in order to spread the tale more widely and hopefully inspire viewers to read the book.

Although this book’s political importance in light of #BLM is often rightly discussed, it’s also simply a beautiful personal narrative. I’ll definitely come back to it when we look at Baldwin and ‘Black English’ and probably to talk about the power of voices as well. On this blog post, I discuss it as a high school teaching text.

Art

Another way that digital music has allowed art to come alive and in constant dialogue is through increasing experimentation with soundtracks to visual art exhibitions.

Bob Duggan pairs music with paintings in Big Think. Though the experience is one to enjoy purely digitally (both the music and the visuals), he discusses the relationship more generally:

The idea of pairing art and music isn’t new, of course. Research focusing on the “synergizing” of music and art arrived at some interesting conclusions about increased appreciation and understanding and, for the initiated, new perceptions that shook up previous judgments. Many museums feature music (usually period-appropriate music) as part of their overall presentation. Taking the art-music coupling to another level, artist-musician Yiannis Kranidiotis created a computer program to translate the colors in a painting into corresponding sound frequencies so you can “hear” what a painting would sound like.

A couple of such exhibitions that he mentions are those at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Exhibition soundtracks at LACMA) and at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA soundtracks for several exhibitions). Sometimes the music is in the museum space itself, but more often, a soundtrack is available either to play on your phone (and headphones) or through museum headphones.

For metal fans, Norway’s Munch Museet put together a cool combination of Edvard Munch’s paintings with music from Satyricon, one of the leading black metal bands. The band produced the music specifically for the exhibit and is described this way by the website:

The intersection of Munch’s expressive motifs and Satyricon’s baseline-heavy music creates room for thought and reflection that goes beyond the realm of black metal alone. Just like Munch, Satyricon’s approach is open and inquisitive, constantly evolving. The exhibition’s music carries Satyricon’s unmistakable signature yet breaks away from anything they’ve previously created through its format, length, and expression.

The show demonstrates the ability of intertextuality to create something new, both for the involved artists and the audience. You can see a video of the curator discussing this process on the museum’s Instagram.

To take it a step further, David Owsley Museum of Art also experimented with music and painting pairings at Ball State University. They added a social media element, encouraging visitors to engage in an online dialogue specifically about the pairings.

Social Media Soundtracks

I won’t say much here, because soundtracks to social media posts are endless…but when do they become a soundtrack instead of simply background music (to a TikTok video, for example)? Does an author have a cohesive and cultivated soundtrack in mind that grows over time on a page, or is each post a separate entity? Surely, they all fit together somehow.

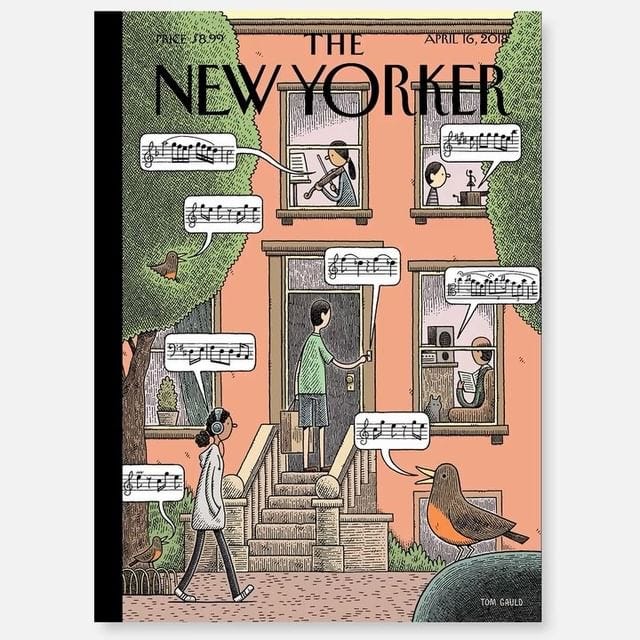

These are questions for another day, but I will leave you with an interesting use of ‘soundtrack’ by The New Yorker:

The caption reads: This week’s cover, “Soundtrack to Spring,” by @tomgauld. (It’s also our first musical cover.) Click the link in our bio to hear more. (April 9, 2018) It was an interactive cover and if you click on the link you’ll see that the live IG video gives you birds tweeting, Beethoven’s “Spring” Sonata No 5 op. 24, and Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” as if coming from the characters on the cover.

Later, we’ll look at musicians in the arts in many other ways. Next week, as the weather is hopefully cooling down wherever you are for outdoor exercise, we move to the Art of Running. Hope you enjoy this web of sound when you have a chance to listen. I’ve posted the Spotify playlist for today and last week’s posts.

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com