Part of the ongoing series on Identity and Culture.

Does the soundtrack to our teenage years define us? It’s made not only of stand-alone music but the music that accompanies experiences, such as viewing films, going on a roadtrip, attending a dance/club/party, having a first kiss/sleepover/job.

Perhaps a secret yearning for the culture of one’s youth can be more easily found in music than in retro fashion or makeup. The sound of a time or the sound of a movement is a cultural collective response to history. It may arrive unbidden — on the radio, at a party, when you open a website. This lack of control makes the experience a part of others’ as well. It is something we can release ourselves to, if we choose.

I’ve made a playlist for today’s newsletter on Spotify. You might want to play the songs to see if they, too, conjure anything for you…to make a collective experience for all of us in this community. Feel free to make your own - just for you - or share a link in the comments.

Youth and memory

The music we know from our youth is proven to help us remember, specifically fond memories. As Kelly Jacubowski et al tell us in “A Cross-Sectional Study of Reminiscence Bumps for Music-Related Memories in Adulthood”:

Autobiographical memory processes play a key role in the construction of a sense of self throughout the course of one’s lifespan (Conway, 2005). Music can be a highly effective cue for autobiographical memories—in particular, positive emotional memories comprising social themes (Jakubowski & Ghosh, 2019; Janata, 2009; Janata et al., 2007), which may be more vivid and embodied than memories triggered by other perceptual cues, such as famous faces or verbal prompts (Belfi et al., 2016, 2018; Zator & Katz, 2017).

I can create many soundtracks in my mind. There was the 1960s music that my gymnastics coach would play until his daughter would do a takeover with early 90s gems that were great for tumbling: Jump and Jump Around come to mind. Still, if I happen to hear Mr. Postman or Leader of the Pack, I’m taken back to backflips and leaps on the balance beam. These songs added a kind of narrative and humor to our time in the gym.

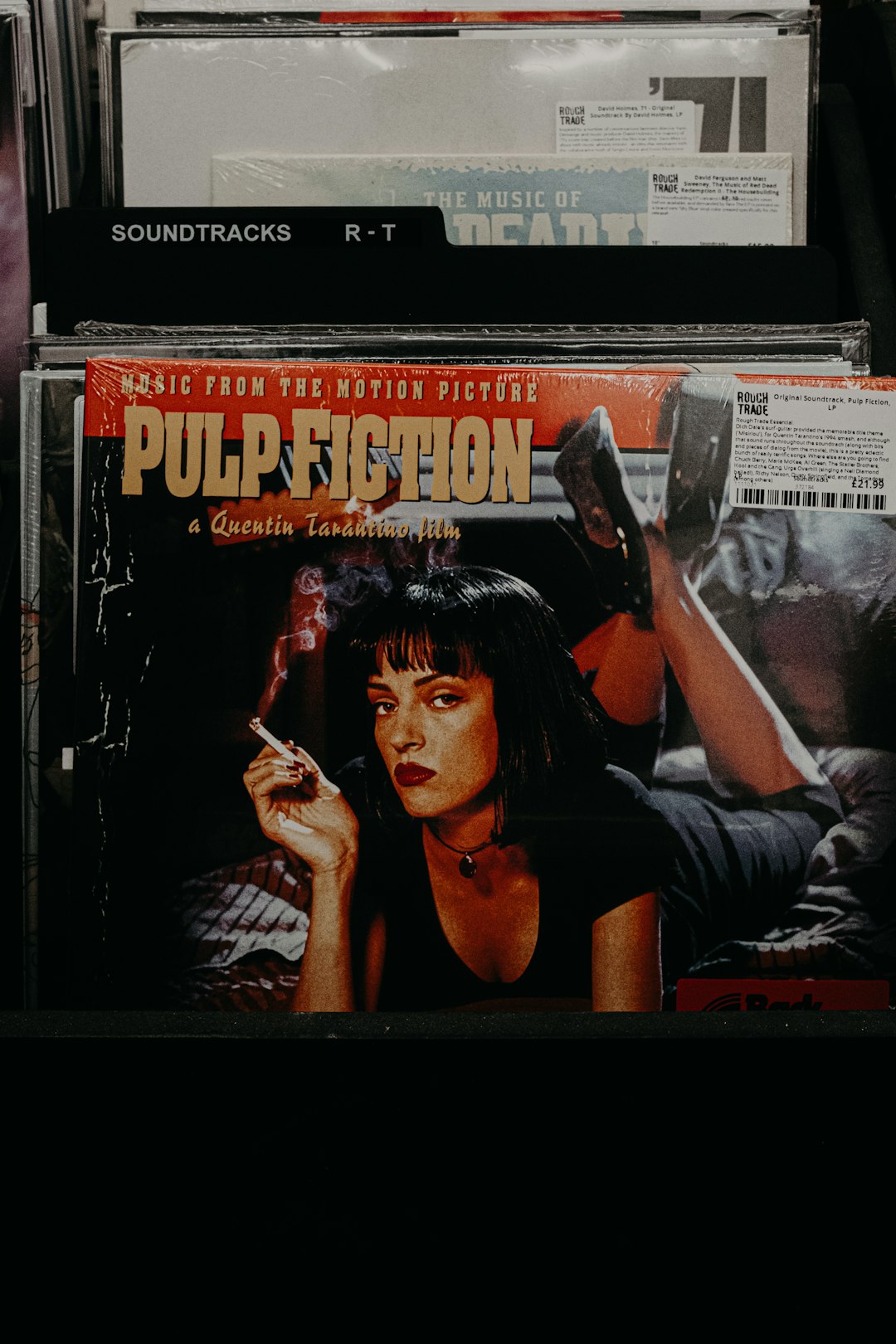

And then there was the soundtrack of hanging out. Music from Pulp Fiction and Friends. Music only listened to in the car (RIP WFNX Boston and Julie Kramer’s Leftover Lunch) or at school dances (Stairway to Heaven was a dangerous in between, much better for hanging out, but often comically used as a slow dance song, only to speed up and confuse already awkward pre-teens on the dance floor; this must have happened for two decades before it was used by the DJs for us, which is why it must’ve been both a mix of humor and sincere appreciation for good music). Music from immortalized bands through death (Nirvana, The Smashing Pumpkins, Sublime, and Jimi Hendrix—even though it was way before our time) reminded us of our mortality, made our time together ephemerally magic.

But there was living music, too. Pearl Jam—how many times did we listen to Yellow Leadbetter (many call it a homage to Hendrix) and air guitar or pretend to know the lyrics without lyric-finder?—I was going to move on, but let me stay with this song a moment! I finally got a chance to see Pearl Jam live at the NOS Alive festival in Lisbon with a surprise appearance from Jack White (starting with a cover of John Lennon’s Imagine). It was incredible…but in respect for the festival providers, they stopped after five encore songs and posted the playlist later…including an unplayed parenthetical final encore: Yellow Ledbetter. Gutted. At least it’s an excuse to see them again.

And here’s my personal shot of Eddie Vedder (who, if you don’t know his solo stuff, also created the soundtrack for the film Into the Wild):

I guess I have to do a newsletter on the politics of Pearl Jam or something of that genre. Later. Personally, it was an interesting time in my life at that concert. My husband was there with me and I was five months pregnant. I was listening to music that recalled the most intimate experiences of friendship from my teenage years and at a festival I had attended single with a friend from my childhood just a couple years previously. There was a lot going on…and this music allowed me to just be with it. To drift in between times and moments and futures.

(Doing this research is fantastic. I’m listening to my favorite songs while I write…this is also probably why I’m getting lost in tangents! But I guess music does that to us all, doesn’t it? It’s sound unleashes a multitude of memory and emotion, of hope and identity…)

Moving on, perhaps because I was teaching teenagers for so long, I kept evolving in my tastes and developed different soundtracks for different moods. My students brought me their favorites and I did the same. It was how I discovered Black Star (with a song about Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye—thanks, Alex) and Chance the Rapper (thank you, Mac). And then, between the artsy-fartsy English departments and musically oriented colleagues, we kept up with the best Indie in the 2000s and 2010s.

Each person I know makes me think of different music, whether they introduced me to it or we listened to it together or they made a playlist for me on Spotify. This is the soundtrack of my life.

Music is linked with memory, as John Legend explains with HeadSpace:

And here’s a cool explanation for kids. However, you might also check out “Narratives of popular music heritage and cultural identity: The affordances and constraints of popular music memories,” which questions the limits of connections between memory and music:

Although those narratives offer a sense of belonging and identity through their connection to experiences of time and place, there are also factors that compromise this potential. The article discusses limits to the accuracy of memories and impediments to representations of local diversity.

There’s also a cool list of references at this link about such topics as music pirates acting as curators and music as cultural heritage.

Music is nostalgic; even if the music was made in a different era, we link it to different parts of our lives and perhaps through the changes in our bodies over time as well.

A communally experienced soundtrack

Collective or cultural memory is a way for us to relate and a way to elevate our human experience. So when artists create with a soundtrack in mind, explicit or implicit, they create layers of meaning and methods of exploration (our memories, our emotions…culture).

Last Christmas, we were back in Boston with my family. Due to COVID, young children, and cold rain, we were both limited with what we could do and wanted to get out of the house for a little bit. Low and behold: the Christmas light soundtrack ride-along in Waltham!

Maybe just because I don’t hear the thick Boston accent much, the ticket seller reminded me of carnivals I had been to as a kid. It felt both a little like home and the entry to some real-life horror movie. I locked the doors, anticipating disgruntled pandemic serial killers hiding in the odd displays. We tuned into the local radio station as directed that was playing particular music to accompany Santa, camels, flags, and huge light tunnels. Bizarre.

The whole thing was admittedly mildly entertaining due to the outrageousness of the sheer number of lights (a million, apparently) and silly Christmas music to go along with it. No, this isn’t a newsletter about Christmas in September. But Christmas in America truly has a public soundtrack, one that we hear in shops and on radio stations…starting way too early. Christmas albums are lucrative and it’s a chance for everyone to be a bit silly and not care about the artistic value of the songs, I guess. Love Actually (2003) teaches us this through “Christmas is All Around.” It’s not the song that’s important, but the narratives that experience it.

There’s fun in a soundtrack. Where is the truth? Is it something to unite us? A free expression in a free space. As music fills up a car, a home, a mall, a concert hall, or a street corner, it inhabits the space with those who occupy it. But it’s also part of the brain — our individual and collective memories. Apparently we can also be brainwashed by music that we may hear unbidden in public spaces (or at the request of the driver in the car, for example). The good news is that research shows we have a pleasurable reaction to music we know, even if we don’t like it. That’s not such a terrible type of brainwashing, but it does bring up many questions about marketing, both in the music industry and through advertisements and social media influencers. Should scroll through those reels with the sound off to keep some semblance of individual free will?

Occupied space

One might investigate this takeover of free space by music through a Foucaultian power perspective implicitly discussed in the articles in Foucault News’ Special Issue on Everyday Politics of Public Space, Space and Culture (2019) or in a recent ruling in Florida restricting loud music to be played from car that can leak into our lives. As Forbes explains:

Florida’s new loud music statute says that it is “unlawful for any person operating or occupying a motor vehicle on a street or highway to operate or amplify the sound produced by a radio, tape player or other mechanical soundmaking device or instrument from within the motor vehicle so that the sound is plainly audible at a distance of 25 feet or more from the motor vehicle.”

Considering that the average car is about 15 feet long, it won’t take much to get a ticket.

Personally, I love a drive-by song sampling. Opera, rap, Britney…I guess it’s sort of obnoxious if it’s too loud? It’s certainly powerful; it commands attention and asserts one’s mutable identity. But if you’re not parked somewhere, I don’t see the problem besides the driver and passengers’ hearing. I also love a passerby with a boombox on their shoulder or bicycle basket. Yeah, it still happens. My husband completely disagrees as I’m sure many of you do, but it amuses me as long as, again, it keeps rolling along.

My music is normally safely contained in my headphones, but what if the Drake I’m walking to is loud enough for the barista to hear when I take out one ear for an order? Or what if the Radiohead I’ve got on while I’m writing is heard by the neighbors below?

In Switzerland, they take their noise control seriously. No ‘loud noises’, including practicing a musical instrument, should be heard during the lunch hour or between evening (some buildings as early as 7 pm!) and morning (6 or 7). Sundays are also off limits. Even buskers have some tight regulations. Is this control or is it freedom (for those who don’t want to hear other’s music, or want to avoid a type of mind control)? Is the threat of a passive-aggressive police call by a neighbor an aural panopticon?

After living in Hong Kong for so long, I understand limiting noise pollution. But at the same time, I wonder what we are missing out on when we suppress musical expression? Is it not a way of expressing oneself? Of attempting to communicate to the rest of the world who is listening: this is what I feel or this is who I am?

Musical bodies

Julia Kristeva’s theories about the distinction between semiotic and symbolic language can be used to understand music as a language. Randi Rolvsjord explains in Music as a Poetic Language:

The semiotic modality is also in the foreground in musical interplay and musical performances. In Kristeva's theory, musical elements turn out to be the characteristics of the semiotic modality in language expressions. Musical elements such as timbre, dynamics, rhythm and intonation articulate the semiotic. But of course as we shall see later, this does not imply that music is exclusively a semiotic language. There is more to music than musical elements, and in Kristeva's terminology, every human language and dialogue is to some degree symbolic.

Kristeva “proposed that bodily drives are discharged in language and that the structure of language is already operating in the body.” With music, we both play it and feel it through the body, whether through dance, the movement of fingers and vocal cords, or the sensation of vibrations. You might also take a look at her book entitled Revolution in Poetic Language (1984).

Derridian Différance tells us that life is a dance. Derrida and Deleuze use dance to represent hope, in different ways. As I explain in my PhD dissertation as a conclusion to discussing dance in various films about immigrants in an earlier chapter:

Deleuze connects dancing to cultural identity formation, linking the creative “collective dance” with simultaneous fragmentation and unity (Cinema 1 62). Derrida explains that “laughter and dance” create “hope” through their expression of independent joy (“Différance” 405). We can further think of music as a type of extension of dance – through movement of body to create art, from our moving limbs, vibrating vocal chords, or tapping fingers. Song is the dance of language. (p. 351)

Last week, I found myself at a festival again for the first time since before the pandemic as well as since I’ve become a mom (I think this only matters because of time available; I’m not saying anything about moms and dads at festivals, because some of my best Clockenflap memories include my best friends with their kids and industrial-sized headphones/noise blockers).

We danced. And we felt the music move through our bodies even when we stood still.

This past week, I finally had the chance to do it again, attend a music festival that is. I went to the Zurich Open Air festival to see Kings of Leon, Bastille, and Two Door Cinema Club. I knew I was missing live music…I just didn’t know how much. We’re still trying to get past this pandemic (etc.), aren’t we?

Bastille especially provided experience not only of beautiful music but also of a space of shared human joy; lead singer Dan Smith pronounced on stage at one point, as if suddenly struck: “It’s so good to be back doing this stuff. We need it!” He also claimed his music was “depressing, sorry,” but I think we also needed to experience a range of emotion together, the thousands of us outside, standing close together, singing to share our experiences from the past few years. They were fun, too, and the highs felt higher because of the lows. Their cover of “Of the night” was a collective dance experience, choreographed by the self-proclaimed awful dancer on stage. We got down nearly to the ground only to get up, jumping for the sky. The movement seemed to echo the emotional journey they were taking us on.

Who says you can’t make youthful memories in your forties? Can we not keep discovering newness in the world and in ourselves with music as the soundtrack, the ideas and emotions that perhaps we cannot fully name, the impressions of life that feel like pieces of art more than reality?

This is only the setup, guys. I haven’t had a chance to really get into the texts yet in an explicitly artistic soundtrack kind of way. I’ll leave that for next week. In the meantime, you can check out the full playlist to this post on Spotify.

This is the third edition of my weekly newsletter: The Matterhorn. Thank you for reading! As a subscriber, you will also receive other articles about writing, reading, art, and culture. Thank you for supporting this initiative! Please share with your friends, students, or colleagues!

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

You are so right about music and memory. It's not only the taste of madeleines. And the playlist - or the mixtape that old timers like me used to make - was and still is an art.

This is the only thing I've attempted on Substack so far: https://giannisimone.substack.com/p/my-favorite-things-1?utm_source=url

I love the playlist! I agree that music has an incredible way of bringing people together and memorializing shared experiences. Thank you for sharing your perspectives!