Part of the ongoing series on Creativity and Representation.

I think I’m not alone in being drawn to portraits at museums, or anywhere really. How often do we get to face somebody else and both admire and scrutinize them, stare at their details in wonder?

Why do artists create portraits? Especially in the age of smartphone cameras creating plenty of memories, what’s the point? Is it purely an aesthetic: the human subject as study? Or is it more than that? I think there’s a part of us, both artist and viewer, who’s trying to understand our own and collective humanity.

To what extent does the artist capture themselves whilst painting (or photographing or drawing…) somebody else? Do we not all try to figure out ourselves or are we somehow supplanted on our subject? Since we each have a subjective view, there is surely by definition a part of ourselves in the portrait.

In a painting class in college, I recall being much more pleased with the outcome of a copy I did of a portrait by Lucian Freud (“Girl Reading”) than I was of a self portrait. Strangely, when I presented the work to the class for our friendly criticism circles and discussions, everyone claimed the painting looked just like me. I had not realized until I took a step back and, yes, I did see the resemblance. However, I’m not sure if I had subconsciously chosen a painting to copy that looked a bit like me or I had painted myself into it. Maybe a mix of the two. In any case, to me it seems that copying a portrait is very different from portraiture, because it takes away the act of depicting something that is alive. Instead, the act is one purely of aesthetics. It is a study of the lines and colors and textures of the original work. It seems there is something unescapable, then, about painting what we have seen or what we know.

Could a photographer or filmmaker do this as well? Does the camera angle or choice of background / time of day / pose (if there is one) reflect the artist themselves? To some extent, it must. So we can think about portraiture as more of a dialogue between subject and artist. The artist has made a decision to capture something. There must be a reason for it.

Self portraits bring up different questions and are often made for different reasons. We’ll take a look at those next week, including - yes - selfies.

I’m thinking about when I encounter portraits. They bombard us online — faces on social media as well as portraits of people on articles or websites. There’s something very different when we see one in a frame, even a family or school portrait, and of course those we see in museums, sometimes after seeing recreations many times over before the in-person experience.

I remember feeling the magic of the Mona Lisa when I finally stood face to face with her in person. I remember staying at Hôtel de Seine in Paris and having two very distinct portraits of unknown people by unknown artists staring at me while I slept. I remember my first trip to the National Portrait Museum in London, home of the largest collection of portraits.

At Art Basel over the years, I’ve been drawn to the lone figure work amongst the abstract. (Here was my write up for the 2022 fair.) This year there were several portraits by Alex Katz, David Hockney, and Kehinde Wiley that made me stop a long time to look despite the thousands of pieces on display. But the one that stood out to me the most was this work (above) by Zhu Jia at ShanghArt called “English Garden” (2019) (better image via the link).

The Chinese artist working mainly in London depicted many ideas in a single image, a portrait of four people. The three at the forefront gaze at the portraitist as if posing or at least aware of their ‘capture.’ The man at the back with a camera is seemingly unaware, and creating his own art. The effect is one of disconnect — insider/outsider, different perspectives — but also one of space. The foreground and background, already aesthetically and geometrically enhanced, are more complex through the competing narratives of the picnic meal, albeit one on a table (no doubt a reference to English culture) and of the photographer who is either appreciating the garden itself or has spotted something - an animal? someone playing hide and seek in the bushes?. Is he photographing because he feels excluded or is it his way of remembering, filtering, and framing the beauty around him?

My preferred portraiture medium is words. I sketch people into my novels. But they’re not portraits because they’re not framed. What I mean is, the people are conglomerates of people I know and don’t know as well as my imagination. The frame and the titling of a portrait by name assumes we are trying to know something about that artist. I guess some of the early sketches in notebooks or Scrivener files could be portraits — a whole thing devoted to a person I’ve encountered; a study of their character, even if I have only viewed them from my perch on a street.

The idea of portraits, I think, is that we get to know something about someone. Have you had the experience of meeting someone in person after meeting them online? I’ve had this in several contexts, and sure online dating is one of them. It’s so hard to read the energy of a person until they are really in the flesh before you. I’ve been surprised in so many ways, not all of them bad. I think that a good portrait captures some energy or personality or mystique about a person that is more than the facts of their life or the aesthetic of their visage. Even in photography, one can capture something. A sort of spirit; and I don’t mean this in a religious way but more like essence of that person and the way they present themselves.

Of course, this energy of our being can change, at least somewhat, every day or every hour. That’s why this notion of live subjects is so important and why the many portraits of the late British queen are so different, not only because of the variety of artists nor the changing wrinkles on her face, but also because of maybe how she felt that day or about that artist. This article from The New York Times discussed the process with three artists who ranged in their intentions from realism to idolization to modernizing the monarchy.

Kings and queens on old palace walls we visit through Europe might be the first thing that comes to mind when we think of portraiture. They tend to blur together in their impressive similarities unless one knows more of the history or particular symbolism in the portrait.

Today, I want to think about portraiture as an inclusive idea — of mediums and motivations — and also of representation. Perhaps a portrait does not really immortalize a person (as they might hope), but it does give them power. This is somewhat ironic because the subject is in the hands of the artist, a passive tool. Their depiction, though, and the framing of that depiction in whatever form it may take, gives the subject a status as someone important enough to be seen. The mere fact that the person is no longer invisible is the through the act of this creation.

What is a portrait?

The word portrait comes from the French past participle of portray, also originally connoting “a figure, drawn or painted.” It was used in this manner since the 1560s according to the Online Etymology Dictionary.

But portraiture, of course, predated this language. London’s Tate Modern has a succinct description of its view on the subject:

Portraiture is a very old art form going back at least to ancient Egypt, where it flourished from about 5,000 years ago. Before the invention of photography, a painted, sculpted, or drawn portrait was the only way to record the appearance of someone.

But portraits have always been more than just a record. They have been used to show the power, importance, virtue, beauty, wealth, taste, learning or other qualities of the sitter. Portraits have almost always been flattering, and painters who refused to flatter, such as William Hogarth, tended to find their work rejected. A notable exception was Francisco Goya in his apparently bluntly truthful portraits of the Spanish royal family.

[I won’t go into Goya today, but his monarchal commissions are fascinating. If you’re not familiar with all the fuss, or even if you are, this article by Edward J. Olszewski is a good read.]

The Tate goes on to discuss how portraiture has changed in the last century or so. Firstly, commissions are “increasingly rare.” Instead, portraits are of family and friends, other artists, or political figures. They also discuss that the change in medium to photography and even video have also changed the nature of the genre, but that “portrait painting continues to flourish.”

To consider this century, we may turn to the National Portrait Gallery of Australia. In a lecture by Andy Nairne, the director of the London similarly named museum, discusses recent portraiture at a talk in Canberra:

The fast changing landscape of surveillance and the globalisation of digital imagery calls for the counterpoint of intense, 'local' imagery contained within a painting. The possibilities of allegory and complex meaning are distinct: the symbolic realm can come to the fore. The conveying of character in a painted portrait is specific and dynamic. There is a process described through paint - an intensity to the relationship between artist and sitter - which produces a different character from the medium of photography. And it is this intensity, often freed from the conventions of previous periods which, gives a great portrait its authority. The painted portrait endures.

London’s National Portrait Gallery has a wide range of works. “The Primary Collection of paintings, sculpture, miniatures, drawings, prints, photographs, silhouettes and mixed/new media works contains 12,696 portraits” and has another “210,000 from the Reference Collections.” You can tell by the list of mediums that even the most famous portrait museum has a wide definition of portraiture: it is the portrayal of a living figure through art.

When I first visited, I expected a bunch of royals over the years, sitting on particular types of furniture or perhaps standing near a horse. A few of those exist there, but so do so many more. It’s a cool place to go and simply ponder the nature of portraiture as well as the nature of humanity. The gallery has diversified their range so that one might consider juxtapositions of different types of people and different types of artistic styles. If you want to think about what is a portrait, this is a great place to go.

Here is the mission of the gallery:

Founded in 1856, the aim of the National Portrait Gallery, London is to promote through the medium of portraits the appreciation and understanding of the people who have made and are making British history and culture, and to promote the appreciation and understanding of portraiture in all media.

So as Britain changes and what is made visible in it, so too does the gallery. The museum is currently closed in order to complete Inspiring People: Transforming Our National Portrait Gallery. In addition to building upgrades, like the entrance, the project aims to “reach[] new audiences locally, regionally and online” and work with communities and youth in different ways.

Famous portraits and their history

Cath Pound investigates the historical significance of portraits in Culture and quotes Alison Smith, chief curator at the National Portrait Gallery in London: "Portraiture stands apart from other genres of art as it marks the intersection between portrait, biography and history. They are more than artworks; when people look at portraits, they think they are encountering that person.”

If you want to read more generally about famous portrait artists, here are a couple of easy starting points:

Artst.org - 11 Most Famous Portrait Artists

Art in Context - Greatest Portrait Painters of All Time

The Met - Portraits of African Leadership

The Big Think - A brief overview of the history of European portraiture

National Gallery of Art - Faces of America: Portraits

BAMPFA - Chinese Portraits

A 1936 article about portraiture begins: “People who tend to value character more than imagination will always be prone to indulge a strong predilection for the art of portraiture.” This is an interesting statement as cubism had already been around for a couple decades. It supposes that perhaps the author (and others) did not consider, for example, Picasso’s cubist paintings of individuals as portraits. The author, Thomas Bodkin, was an art historian and lawyer.

In fact, Bodkin seems most concerned with the likeness to real life, as this sentence suggests: “A group of portraits of John Philpot Curran by various artists, now to be seen in the National Portrait Gallery of Ireland, most of which have not yet been reproduced, exemplifies well the profound differences which can exist between authentic likenesses of the same individual.” This seems strange to me because the painting will never compete on the level of the ‘real’ with photographic portraits, which had been well established for some 50 years at that point. However, other contemporary artists work toward this realism in captivating ways, such as Gerhard Richter (sometimes) and Leng Jun. Bodkin concludes in a yearning for accuracy of historical depictions through photography, but also in discussion of art. Whilst this documentation of history is certainly useful, he seems to miss the point of artistry as well in portraiture.

A few decades later, comes discussion about reinventing the nature of portraiture but still within a more realistic representation of the figure. A good example of this is David Martin’s “On Portraiture: Some Distinctions” (1961).

And what is that point? Is it the same as the point of all art? Which, of course, has a variety of responses, ranging from aesthetic beauty to political discourse to uses of the imagination or a combination of answers. Surely the point of portraiture is partly to document one’s life, one’s personality or achievements. It immortalizes them and captures elements of their character. What do we see when we view these portraits? We understand others. But maybe we also understand ourselves a bit more through the elements we respond to or how we feel when we view the work: what part of me is in that portrait?

Vincent Van Gogh is known especially for his self portraits, which we will take a look at next week. But he also did portraits of others. As an Expressionist, he was interested in capturing feelings through changes of color and line. E.H. Gombrich’s quintessential The Story of Art explores the nature of this artistry also as a reimagining of African sculpture and ‘tribal art,’ but one that was often met by distaste from the public. Gombrich discusses the way Van Gogh and Munch were more interested in understanding a reality that includes pain and sadness instead of a fake, happy idealization of beauty. (pp. 562-565)

Gombrich quotes Van Gogh discussing his portraiture style to a friend:

I exaggerate the fair colour of the fair, I take orange, chrome, lemon colour, and behind the head I do not paint the trivial wall of the room but the Infinite. I make a simple background out of the most intense and riches blue the palette will yield. The blond luminous head stands out against this strong blue background mysteriously like a star in the azure. Alas, my dear friend, the public will see nothing but caricature in this exaggeration, but what does that matter to us? (p. 564)

Von Gogh then is more interested in ideas about “the Infinite” and mystery, the inner workings of the human soul and the universe, than in the realistic aesthetic interpretation.

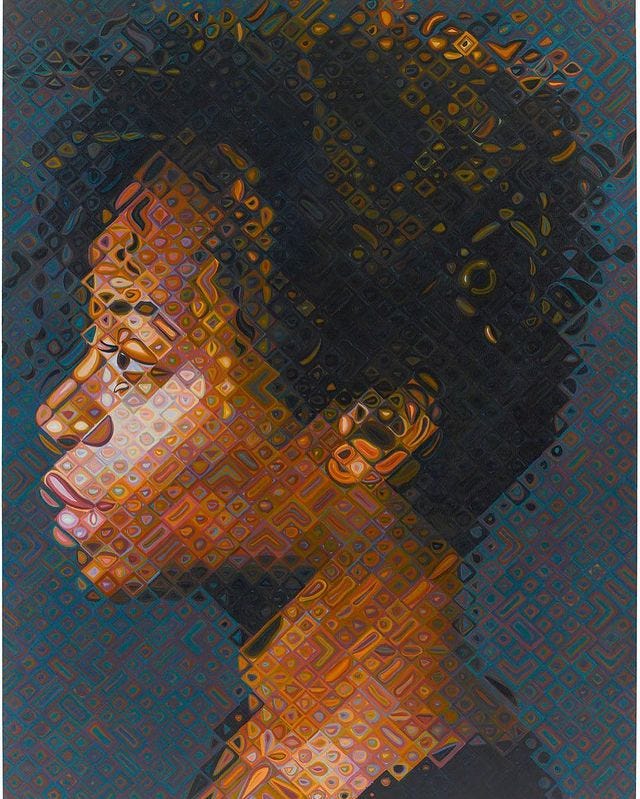

In a similar way, one could say that portrait artists Chuck Close and Alex Katz play with color as a type of hyperreal quality to a person. Whilst this portrait above of artist Kara Walker is at once abstract and true to life in a recognizable fashion, his signature use of squared color designs on a grand scale give her a kind of vibrancy and life force almost more visceral than a person in the flesh (though I have never met Ms. Walker myself — who knows?).

I recently went to see an exhibit at Basel’s Kunstmuseum: Picasso - El Greco. The show was mainly made up of portraits and investigated the way Picasso’s decidedly more abstract work drew heavily on influence from El Greco, also noting the latter’s avant garde style some 350 years earlier. There were quotes also from Picasso discussing the way he saw all artists’ works as living, as if they were there with him while he painted. He felt that he was in dialogue with these great artists and that the paintings were then more than just images: they entered the dialogue immediately as both a representation of the subject and artist as well as its own living thing. Above, you can listen to Picasso’s daughter talk about the exhibition. A video from the curator is also available.

All painting flattens us into 2D space, so that the artist has to make choices of interpretation. It abstracts the human form, emphasizing the idea that we are all more than the sum of our parts / we are an idea, an energy of being… This is part of the idea of cubism, to both break apart the image and force us to use our imagination to put it back together.

It is as if we are having a conversation with that human form on the wall, that is both the subject and not, the painter/photographer and not.

Changes in style & medium

The obvious reason there are so many painted portraits commissioned historically from famous painters was that they pre-dated the photograph. People wanted to be portrayed a certain way (on a different level from filters) and to be remembered (this way) immortally. But no matter what their desires, the power was still in the hands of the artist.

But we can go beyond even purely visual representations of figures to link portraiture to work in language. As I mentioned in the introduction, this is my medium of portraying people.

Any biography or feature piece about a person is a type of portrait. Some writers are known for their rich biographies, like Doris Kearns Goodwin and Hermione Lee. Lunch with the FT as a portrait of unexpected person through lunch interview every week. The Profiles section of The Guardian paints a picture of a variety of famous people.

Journalistic portraits are also sometimes in podcast form, like Oprah’s Super Soul or A Real Piece of Work (the job podcast for young people). Desert Island Discs is both a spoken and musical portrait, not only but often of musicians (like Bono, in the case below).

Films to Be Buried with instead tells a life story through cinema. In the same genre, but also with video, James Cordon’s Carpool Karaoke gave a short portrait of a celebrity through song and chatting in the car.

Film biopics have captured many portraits over the years, blending the visual with language and presenting a more dimensional investigation of the subject. Here is a list on IMDB of the 50 Greatest Biopics of All Time. Films about celebrity subjects are often criticized for leaving things out, usually the less forgiving parts of their lives or characters, but don’t we do this to an even greater extent in painted portraiture? A few recent ones I enjoyed that might fit into this category are Bohemian Rhapsody (Bryan Singer 2018, of Freddy Mercury), Rocketman (Dexter Fletcher 2019, of Elton John), and September Issue (R.J. Cutler 2009, of Anna Wintour). Clearly even an hour or two of someone’s life, while much more drawn out than a still image, cannot provide all that much of who they really are. Instead it is a portrait: a framed capture of a figure.

Family videos and photos do this, too. We may feel these days that we have endless imprints of family members, giving us the full picture. But even the extra cloud spaced I purchased to hold onto these memories of my son (and others) cannot tell the whole picture.

Is it different to have family portraits on digital display frames vs framed stills on bookshelves or hung on walls? What does it say if you have a load of these printed photos…or none at all?

I remember a family friend’s house growing up whose entire upstairs of their house was covered with hung family photos. There was barely a spot of wall uncovered. Was this an aesthetic decision? Probably not. Was it a way to hold onto memories? Or to create a narrative of this family’s history? Editing the parts that made it good? It seems like a precursor to social media photo sharing; even though it was in the home, it was put on display for guests. (Sure, it was upstairs, but these people had a lot of guests around…) I’m not critiquing it, but it must sound like I am. I’m more fascinated with the process. And I’m also wondering: where are those photos now? The family has moved; the children are grown up with children of their own. Have they all taken these framed photos with them or have they been placed in an album? Or digitized? Was it more important for the mother who created the display to go through the process of creation? In other words, perhaps she gained something simply by framing, some kind of memory or important processing mechanism about the narrative of her family.

I meant to come back and expand on framing here, but I’ve got way too much today. I’ve mentioned Jacques Derrida’s The Truth in Painting (La Vérité en Peinture) before, which offers, among other things, a way of understanding a text through its frames, which include titles, although likewise insisting these do not change the inner work; they simply add a layer of interpretation.

Sarah Medlam investigates the purpose and history of the frame for the Furniture History Society journal in “Callet’s Portrait of Louis XVI: A Picture Frame as Diplomatic Tool” (2007). She discusses the way the frame embellishes the message of the portrait itself:

The frame similarly reflects the status that Louis XVI desired to project and, in particular, displays a trophy that spoke of his military power, even if that power had recently been laid aside for the resumption of peaceful relations with Britain. The frame itself is fairly regular in form, with bold cartouches at the corners, but the carving is sharp and carefully graded in quality, with most of the decoration in the cresting, where it would have been visible even across the crowded rooms of an ambassadorial reception.

I’ll leave it at that for now. One might consider how a social media app itself is a frame to a portrait. Or, there are multiple frames: the phone/device, the app, the user profile, perhaps a title or caption, and maybe even an aesthetic frame. How does it change the way we view the image? And how do these apps allow for greater representation and visibility by larger audiences?

Representation

The use of photography also made it easier to more quickly depict different types of people and to reprint these images, whether in magazines or simultaneous exhibitions. Of course now, we can spread an image around the world with one click of a finger.

New York City based photographers Diane Arbus and Vivian Maier similarly set out to capture less visible people in the 1950s and 60s. Arbus grew up rich and felt that she didn’t get to know different types of people. MOMA’s exhibition site tells us: “Perhaps because Arbus believed that she had not been sufficiently tested by adversity, she sought it out in the world around her.” The Guardian has a small gallery of her work nicely displayed. Maier’s work can be seen on her website. As Brittanica says, “[h]er preferred subjects were children, the poor, the marginalized, and the elderly.”

In some ways, their photographs are portraits of the city itself. Portrait can also be of a place, in this case of a slum or of a neighborhood in transition.

I talked with Mike Ritter about this back in October. His photography is primarily about representation; his recent projects create seated portraits of people in mainly poor communities in the Boston area and display them in public settings, including the Boston Public Libraries.

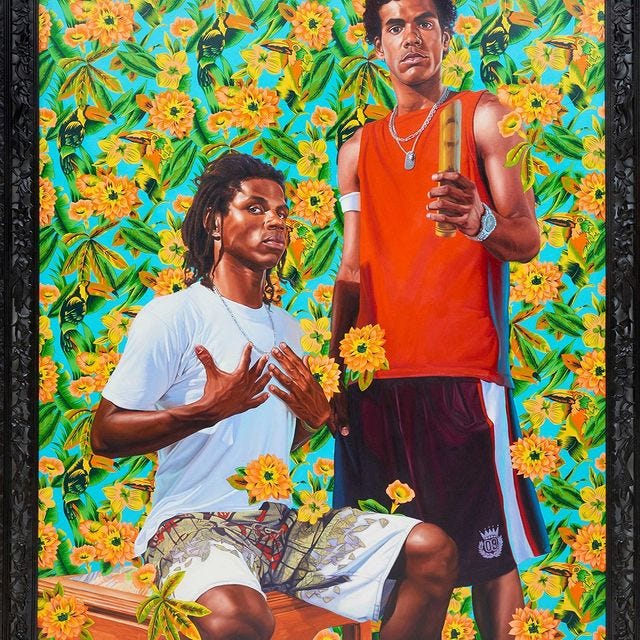

Talking to my old art history classmate was really fun; he’s also creating a dialogue through his art. A recent work that was a photographic pastiche of one of Kehinde Wiley’s paintings was accepted by Boston’s MFA in a contest.

Above is “Marechal Floriano Peizoto II” by Kehinde Wiley at the Boise Art Museum (Idaho, USA). The treatment of his work as part of the tradition and dialogue of famous portraiture is at the forefront of his work. This statement is fixed like a mission at the start of the artist’s website:

Los Angeles native and New York based visual artist, Kehinde Wiley has firmly situated himself within art history’s portrait painting tradition. As a contemporary descendent of a long line of portraitists, including Reynolds, Gainsborough, Titian, Ingres, among others, Wiley, engages the signs and visual rhetoric of the heroic, powerful, majestic and the sublime in his representation of urban, black and brown men found throughout the world.

He represents a range of race that had been largely invisible in this type of grand scale portraiture.

Similarly, the film Quest: a portrait of an American family is a documentary about a normal Black family in Philadelphia. The website also links the setting to the time of the Obama administration, of whom Wiley is also famous for painting Borack and Michelle’s portrait:

Beginning at the dawn of the Obama presidency, Christopher "Quest" Rainey, and his wife, Christine'a "Ma Quest" raise a family while nurturing a community of hip hop artists in their home music studio. It's a safe space where all are welcome, but this creative sanctuary can't always shield them from the strife that grips their neighborhood. Epic in scope, QUEST is a vivid illumination of race and class in America, and a testament to love, healing and hope.

Portraits have long been political, asserting power or giving power to the marginalized. Ai Wei Wei is known as one of the most political artists of our century, enhanced by his exile from China.

The above image is from a collaboration between the artist and Shepard Fairey. According to Widewalls (who also has an interesting overview of contemporary portraiture):

Shepard Fairey created a print which articulated the artistic expression of Gao Yuan’s photograph depicting Ai Weiwei with a visible scar and Fairey’s devotion to spread socio-political commentary on the current situation in the world of art and activism. The Chinese artist’s scar was obtained due to a head injury inflicted by the Chinese police in Chengdu in 2010.

Something as small as a scar can have a global political message. Additionally, the Warhol-like print makes Ai into an icon; we may conjure JFK, Marilyn Monroe, or even Mao.

Portraitists in fiction

Probably the most famous portrait in literature is that of Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (originally 1890 in serial form, 1891 as a book). I have written about the preface before - “All art is quite useless.”

Basil Hallword, the portraitist, paints the beautiful youth - Dorian Gray - and his painting seemingly takes on the strange trait of aging as Dorian maintains his youthful visage. Conversations among Basil, Lord Henry, and Dorian consume the pages, offering a variety of opinions about beauty, relationships, truth, and - yes - portraiture.

Here is something from Basil, the artist:

“Harry…every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely an accident, the occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself. The reason I will not exhibit this picture is that I am afraid that I have shown in it the secret of my own soul.” (p. 9)

Fascinating, then, that the surreal quality of the narrative makes the painting into something so grotesque that seems to absorb and reflect the character of Dorian, a murderer. But if Basil is correct, then this disgust is really that of the painter himself. However, it may point to a wider truth that we are all sinners, or that we all have secrets. Perhaps it is simply a reflection of humanity.

A couple of other texts that investigate these ideas are J.D. Salinger’s short story “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period” (1951) and Natsume Sōseki’s novel The Three-Cornered World (Kusamakura, 1906). Both also include many references to visual artists in other works.

Another Japanese writer who often includes visual arts and music in his novels is Haruki Murakami. His most recent novel, Killing Commendatore (2017), includes a portraitist as protagonist, living in the home of another portraitist (currently in a nursing home).

The narrator, who is going through a difficult personal experience of disillusion following separation from his wife, tells us at first that portraits are more functional than art, but this is subverted over the course of the novel.

Murakami offers a differing view that the portrait gives us the window to the sitters soul as well as creating political and historical dialogue. A narrative from WWII is weaved through the story and includes a Warsaw prisoner who was a professional painter. He did portraits “for the Germans” because he had to; but he says: “‘Believe me, I would rather paint black-and-white pictures of the children in the piles of corpses in the Lazarett than the Germans’ families. Give ‘em pictures of the people they murdered; let ‘em take them home and hang them on the wall, the sons of bitches.’”

A climactic point is when a neighbor and art student sits for a portrait:

“If I can draw you the right way, maybe you’ll be able to see yourself through my eyes,” I said. “If all goes well, of course.”

“That’s why we need pictures.”

“You’re right—that’s why we need pictures. Or literature, or music, or anything of that sort.”

If all goes well, I said to myself.

“So let’s get started,” I said to Mariye. Looking at her face, I started mixing the brown for the underdrawing. Then I selected the first brush I would use on the painting. (p. 438)

These ideas develop through a series of sittings. Earlier, the painter shows a portrait to Mariye of somebody else:

“This painting is more than powerful enough as it is…Do you know the man in the painting well?”

I shook my head. “No, to tell the truth he’s a complete stranger. I ran across him a while back. In a faraway town when I was on a long trip. We never talked, so I don’t know his name.”

“I can’t tell if the power is good or not…”

“And you don’t think I should let that power come to the surface, right?”

…

I took the canvas from the easel and set it back down on the floor, facing the wall. The moment its surface was hidden, the tension in the studio released its grip. It was a tangible sensation. (p. 375)

Both novels have surreal qualities but the ideas are in ‘real life.’ We can feel a negative energy from a painting that helps us understand a situation or person or more abstract idea. It is a response to this power that is important. What portraits have made you feel this way? When does a life force seem to jump out from the painting? When have you had to turn away or when have you been drawn to one, as if under a spell?

Further reading

One might also investigate the way Walter Benjamin considers an early photographic portrait of Franz Kafka in Sur la Photographie (On Photography, originally in German), also discussed in this article by Michael G. Levine.

Susan Sontag’s similarly named book: On Photography (this time in English) is another one to investigate the need for photographic portraiture’s ugly side. As curator Mia Fineman tells The Art Newspaper: “On Photography explores the ethical implications of camera vision in the realm of reportage…The voyeurism and complicity involved in taking and looking at photographs of atrocity, and the dangers of compassion fatigue, of becoming desensitised to images of suffering.”

Back to painting, the history of Picasso’s portraiture is a fascinating one, albeit long. If you haven’t encountered the biographical series of four tomes by John Richardson, it is a lengthy but worthwhile project to read. The understanding of his portrait’s subjects, in particular, will help you look at the works in a new light.

Portraits are powerful. I like the idea of framing myself through different times and moods; making myself into a symbol of an idea. Maybe that’s what we do with self portraits…and selfies. That’s what we’ll look at next week. Thanks a lot for reading and please share your thoughts or favorite portraits with our community here.

Kathleen Waller is a novelist with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She previously taught literature, cultural studies, art, ethics, and epistemology to high school and university students for twenty years. For more information: kathleenwaller.com

Fascinating post - and interesting that we both wrote about portraits/self-portraits in out respective Substacks this week!

I am very drawn (!) to the idea of portraits. Here in Spain I have been thinking about the genre of portraiture (in paint) and in words - as an abstract artist and a fledgling poet, I am wondering about how/who/why portraiture? Could I ? Should I ? Who? Me?

When?

Back in Donegal and my studio from the end of January

‘We’ shall see